Key Takeaways:

Predicting meteor rates, particularly for the highly variable Leonid shower, is akin to estimating the number of snowflakes that will fall on an area of ground. You simply can’t know until it’s all over. And in the case of this event, you’ll know only if you’re outside observing.

The remarkable activity that observers witnessed during 1999 (a rain of fireballs [meteors bright enough to cast a shadow]) and 2000 (more than 1,000 meteors per hour for a brief period) came about because the shower’s parent comet, 55P/Tempel-Tuttle, had passed through the inner solar system in 1998.

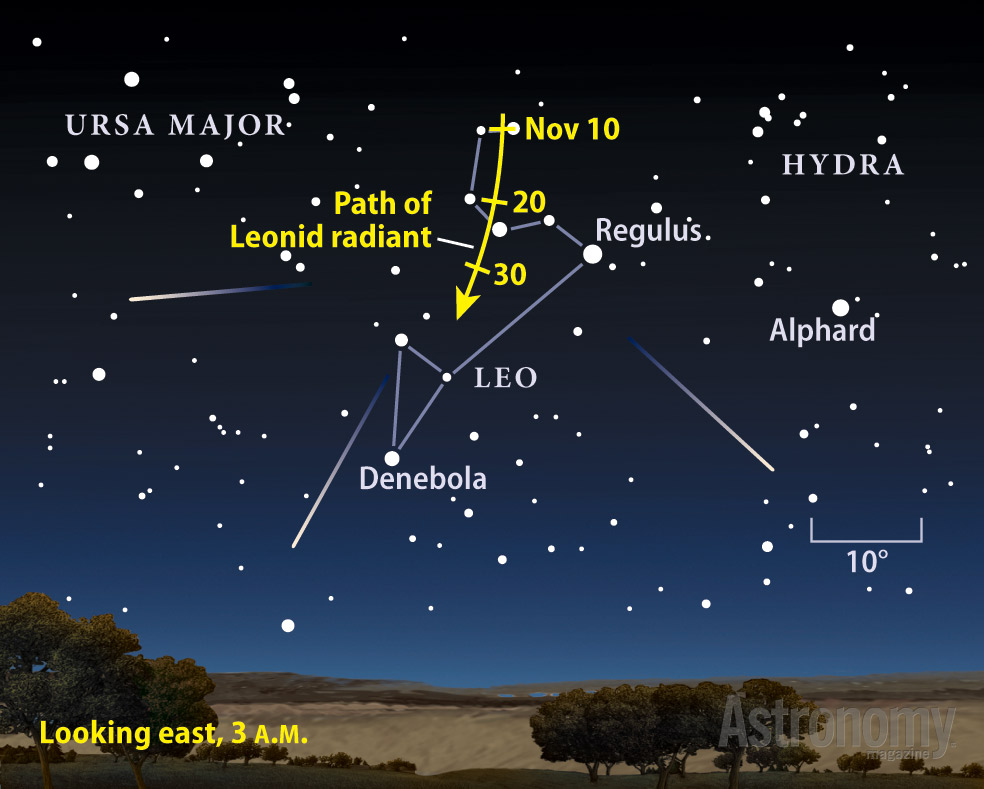

This year, predictions are more modest, but spikes in activity can occur at any time. The shower’s peak occurs across North America before dawn November 17. The Moon reaches First Quarter on the 20th, so it will only interfere if you observe before moonset, around 10 p.m. local time. Even then, bright Leonids should shine through nicely.

Particles in the Leonid shower are debris shed by the comet 55P/Tempel-Tuttle. In 1865, astronomer Ernst Tempel discovered the comet, and in 1866, another astronomer, Horace Tuttle, independently found it. The comet itself measures about 2.5 miles (4 kilometers) in diameter and orbits the Sun with a period of slightly more than 33 years.

As it makes its closest approach to the Sun, it also passes close to Earth’s orbit. This last happened February 28, 1998. Our 2012 encounter with the debris stream from Tempel-Tuttle will last several days, but the most intense part (when we’ll see the most meteors) typically lasts only two to three hours.

Leonid meteors are fast (they move at more than 40 miles [65km] per second), and some leave smoke trails that can last a number of seconds. Many Leonids are also bright. Usually, the meteors are white or bluish-white, but in recent years some observers reported yellow-pink and copper-colored ones.

Take a lawn chair, cookies, fruit, and a nonalcoholic beverage. (Alcohol interferes with the eye’s dark adaption as well as the visual perception of events.) Most importantly, dress warmly, preferably in layers, and bring extra blankets. Leonid watching involves no movement or exercise. You’re either sitting or standing, and — because it’s November — you will get cold.

The best advice you’ll hear is to observe after midnight. This is the time when those locations on Earth face the direction our planet orbits the Sun. After midnight, then, Earth is running into the meteor stream.

If you can head out only after sunset, face generally east and look one-third to one-half of the way up in the sky. Glancing around won’t hurt anything. Between moonset (10 p.m.) and about 2 a.m., look overhead. And after 2 a.m., aim your gaze halfway up in the western sky.

“All meteor showers are fun events,” says Reynolds. “Hopefully, this year’s Leonids will feature some bright meteors. Pick out a dark site, stay warm, and get ready to cheer.”

- Video: How to observe meteor showers, with Michael E. Bakich, senior editor

- Video: Easy-to-find objects in the 2012 autumn sky, with Richard Talcott, senior editor

- StarDome: Locate the shower’s radiant in Leo in your night sky with our interactive star chart.

- The Sky this Week: Get your Leonid meteor shower info from a daily digest of celestial events coming soon to a sky near you.

- Sign up for our free weekly e-mail newsletter.