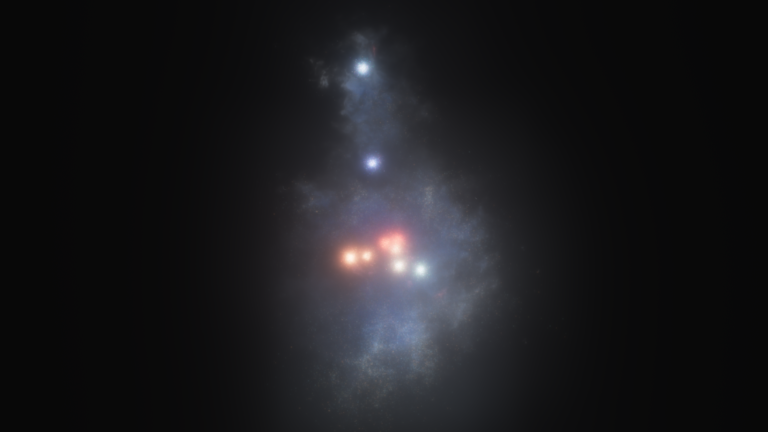

The LMC is ablaze with star-forming regions. From the Tarantula Nebula, the brightest stellar nursery in our cosmic neighborhood, to LHA 120-N 11 (N11), part of which is featured in this Hubble image, the small and irregular galaxy is scattered with glowing nebulae — the most noticeable sign that new stars are being born.

The LMC is in an ideal position for astronomers to study the phenomena surrounding star formation. It lies in a fortuitous location in the sky, far enough from the plane of the Milky Way that it is neither outshone by too many nearby stars nor obscured by the dust in the Milky Way’s center. It is also close enough to study in detail — less than a tenth of the distance of the Andromeda Galaxy, the closest spiral galaxy — and lies almost face-on to us, giving us a bird’s-eye view.

N11 is a particularly bright region of the LMC, consisting of several adjacent pockets of gas and star formation. NGC 1769, which is in the center of this image, and NGC 1763, which is to the right, are among the brightest parts.

In the center of this image, a dark finger of dust blots out much of the light. While nebulae are mostly made of hydrogen, the simplest and most plentiful element in the universe, dust clouds are home to heavier and more complex elements, which go on to form rocky planets like Earth. Much finer than household dust, this interstellar dust consists of material expelled from previous generations of stars as they died.

The data in this image were identified by Josh Lake, an astronomy teacher at Pomfret School in Connecticut, in the Hubble’s Hidden Treasures image processing competition. The competition invited members of the public to dig out unreleased scientific data from Hubble’s vast archive and to process them into stunning images.