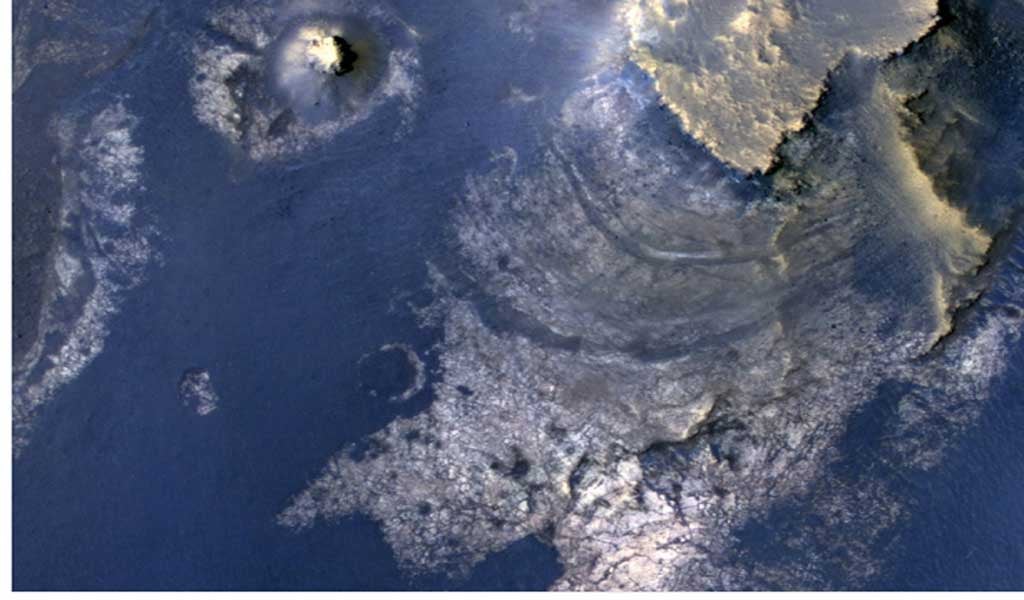

The new information comes from researchers analyzing spectrometer data from NASA’s Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO), which looked down on the floor of McLaughlin Crater. The martian crater is 57 miles (92 kilometers) in diameter and 1.4 miles (2.2km) deep. McLaughlin’s depth apparently once allowed underground water, which otherwise would have stayed hidden, to flow into the crater’s interior.

Layered, flat rocks at the bottom of the crater contain carbonate and clay minerals that form in the presence of water. McLaughlin lacks large inflow channels, and small channels originating within the crater wall end near a level that could have marked the surface of a lake.

Together, these new observations suggest the formation of the carbonates and clay in a groundwater-fed lake within the closed basin of the crater. Some researchers propose the crater interior catching the water and the underground zone contributing the water could have been wet environments and potential habitats.

“Taken together, the observations in McLaughlin Crater provide the best evidence for carbonate forming within a lake environment instead of being washed into a crater from outside,” said Joseph Michalski of the Planetary Science Institute in Tucson, Arizona, and London’s Natural History Museum.

Michalski and his co-authors used the Compact Reconnaissance Imaging Spectrometer for Mars (CRISM) on the MRO to check for minerals such as carbonates, which are best preserved under nonacidic conditions.

“The MRO team has made a concerted effort to get highly processed data products out to members of the science community like Dr. Michalski for analysis,” said Scott Murchie of the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory in Laurel, Maryland. “New results like this show why that effort is so important.”

Launched in 2005, the MRO and its six instruments have provided more high-resolution data about the Red Planet than all other Mars orbiters combined. Data are made available for scientists worldwide to research, analyze, and report their findings.

“A number of studies using CRISM data have shown rocks exhumed from the subsurface by meteor impact were altered early in martian history, most likely by hydrothermal fluids,” Michalski said. “These fluids trapped in the subsurface could have periodically breached the surface in deep basins such as McLaughlin Crater, possibly carrying clues to subsurface habitability.”

McLaughlin Crater sits at the low end of a regional slope several hundreds of miles (kilometers) long on the western side of the Arabia Terra region of Mars. As on Earth, groundwater-fed lakes are expected to occur at low regional elevations. Therefore, this site would be a good candidate for such a process.

“This new report and others are continuing to reveal a more complex Mars than previously appreciated, with at least some areas more likely to reveal signs of ancient life than others,” said Rich Zurek of NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California.