A 150-foot-wide (45 meters) asteroid called 2012 DA14, discovered just a year ago, will pass only 17,200 miles (27,700 kilometers) above Earth. That’s closer than the geosynchronous communication and weather satellites. While the object definitely will not strike Earth, this is a record close approach for an object of this size. Astronomers around the world are preparing to take advantage of the event to study the asteroid.

A team, including Michael Busch from NRAO, will use a novel observing technique to determine which way the space rock is spinning as it speeds on its orbit through the solar system. The direction of its spin is an important factor in predicting how the object’s orbit will change over time.

“Knowing the direction of spin is essential to accurately predicting its future path and thus determining just how close it will get to Earth in the coming years,” Busch said.

Busch’s team will use the Karl G. Jansky Very Large Array (VLA) and the Very Long Baseline Array (VLBA) antennas at Pie Town and Los Alamos, New Mexico, along with a solar system radar on NASA’s 230-foot (70 meters) antenna at Goldstone, California. The Goldstone antenna will transmit a powerful beam of radio waves toward the asteroid, and NRAO’s New Mexico antennas will receive the waves reflected from the asteroid’s surface.

Because of the asteroid’s uneven surface and the different reflectivity of portions of the surface, the reflected radar signal will have a characteristic signature, or “speckles,” as observed from Earth. By measuring which antenna in a widely separated pair receives the speckle pattern first, the astronomers can learn which way the asteroid is spinning. This way of using the telescopes is significantly different from their normal astronomical observing, and the research team has developed special techniques for processing the data.

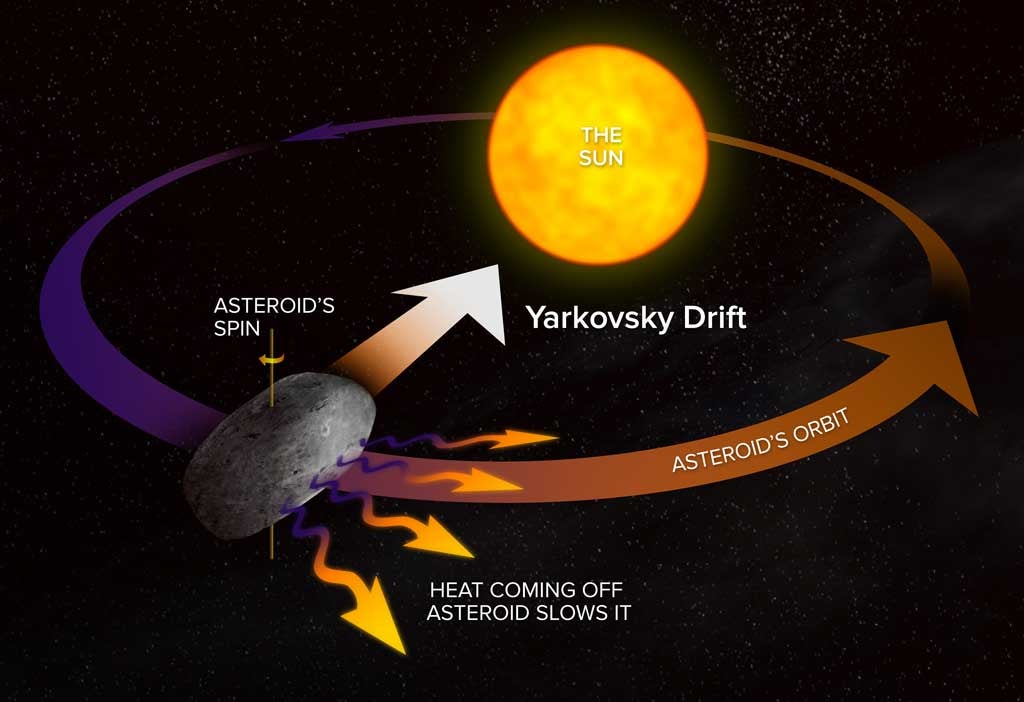

How does this tell astronomers anything about the asteroid’s orbital changes? Just as the afternoon is the warmest part of the day on Earth, the space rock develops a warm region that radiates infrared light in its maximum amount during “afternoon” on the asteroid. That outgoing infrared radiation provides a gentle but firm jetlike push to the asteroid. The direction of the asteroid’s spin determines whether “afternoon” is either forward or rearward of its direction of motion.

If the hot spot is forward of the direction of motion, the infrared push will slow the asteroid’s orbital speed, and if the hot spot is rearward of the direction of motion, it will speed up the orbital motion. This effect, over time, can make a significant change in the orbit. This is called the Yarkovsky effect, after the engineer who first identified it.

“When the asteroid passes close to Earth or another large body, its orbit can be changed quickly by the gravitational effect of the larger body, but the Yarkovsky effect, though smaller, is at work all the time,” Busch said.

The Goldstone-VLA-VLBA observations will be made February 16 when the asteroid’s south-to-north motion in the sky makes it readily visible to those antennas.