Every 25.34 days, the object, designated LRLL 54361, unleashes a burst of light. Although a similar phenomenon has been observed in two other young stellar objects, this is the most powerful such beacon seen to date.

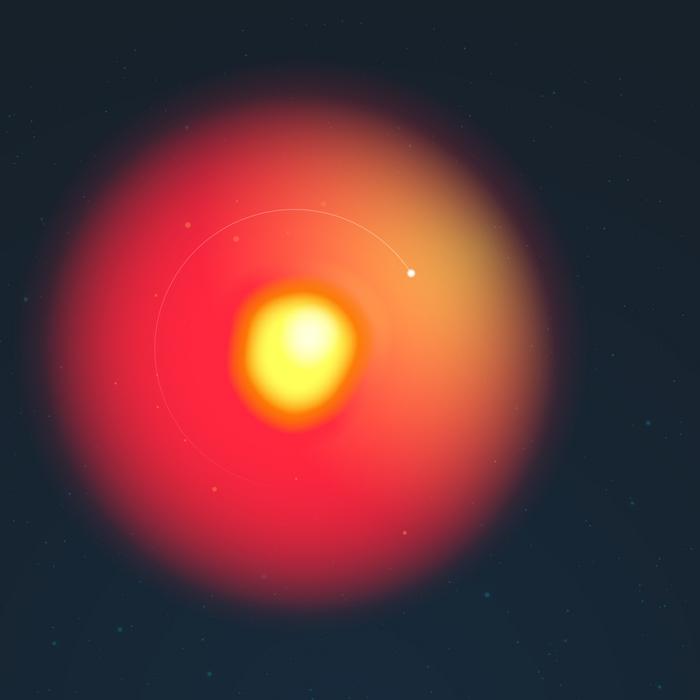

The heart of the fireworks is hidden behind a dense disk and envelope of dust. Astronomers propose the light flashes are caused by periodic interactions between two newly formed stars that are binary, or gravitationally bound to each other. LRLL 54361 offers insights into the early stages of star formation when lots of gas and dust are being rapidly accreted — pulled together — to form a new binary star.

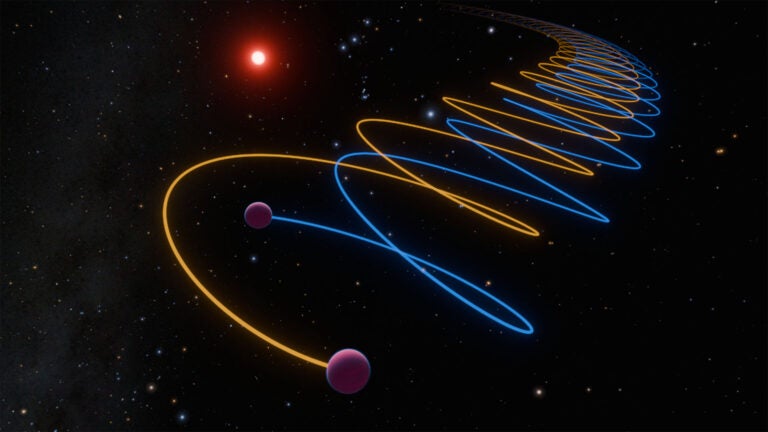

Astronomers theorize the flashes are caused by material suddenly being dumped onto the growing stars, known as protostars. A blast of radiation is unleashed each time the stars get close to each other in their orbits. Astronomers have seen this phenomenon, called pulsed accretion, in later stages of star birth but never in such a young system or with such intensity and regularity.

“This protostar has such large brightness variations with a precise period that is very difficult to explain,” said James Muzerolle of the Space Telescope Science Institute in Baltimore, Maryland.

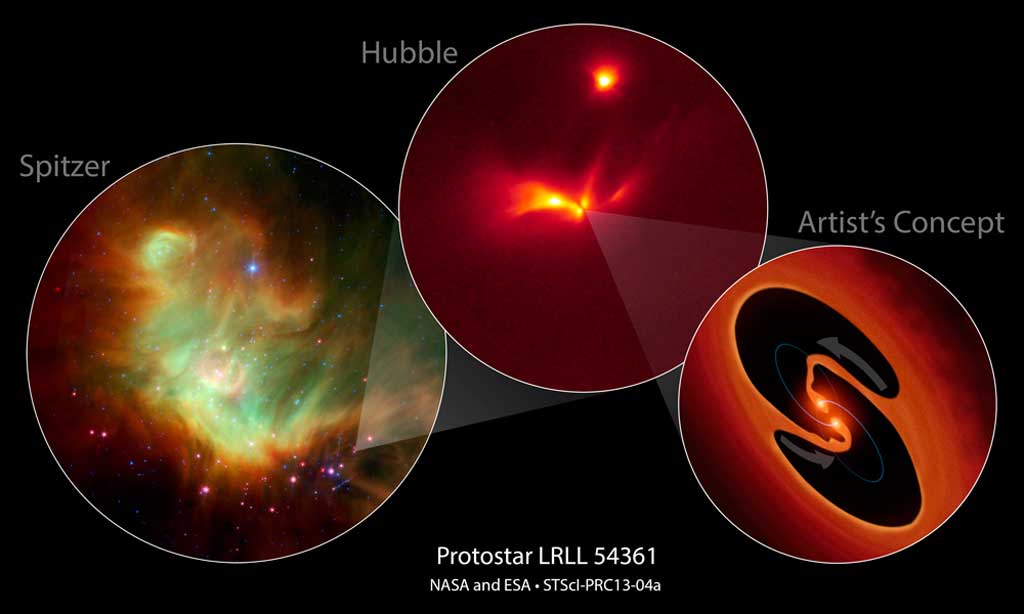

Discovered by NASA’s Spitzer Space Telescope, LRLL 54361 is a variable object inside the star-forming region IC 348, located 950 light-years from Earth. Data from Spitzer revealed the presence of protostars. Based on statistical analysis, the two stars are estimated to be no more than a few hundred thousand years old.

The Spitzer infrared data, collected repeatedly during a period of seven years, showed unusual outbursts in the brightness of the suspected binary protostar. Surprisingly, the outbursts recurred every 25.34 days, which is a rare phenomenon.

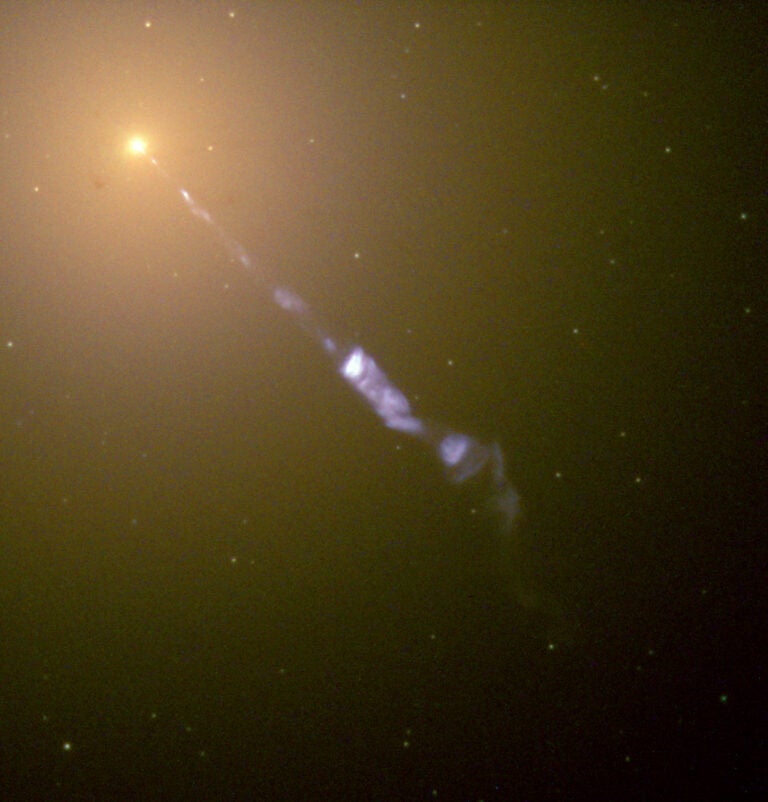

Astronomers used NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope to confirm the Spitzer observations and reveal the detailed stellar structure around LRLL 54361. Hubble observed two cavities above and below a dusty disk. The cavities are visible by tracing light scattered off their edges. They likely were blown out of the surrounding natal envelope of dust and gas by an outflow launched near the central stars. The disk and the envelope prevent scientists from observing the suspected binary star pair directly. By capturing multiple images over the course of one pulse event, the Hubble observations uncovered a spectacular movement of light away from the center of the system, an optical illusion known as a light echo.

Muzerolle and his team hypothesized that the pair of stars in the center of the dust cloud move around each other in a very eccentric orbit. As the stars approach each other, dust and gas are dragged from the inner edge of a surrounding disk. The material ultimately crashes onto one or both stars, which triggers a flash of light that illuminates the circumstellar dust. The system is rare because close binaries account for only a few percent of our galaxy’s stellar population. This is likely a brief, transitory phase in the birth of a star system.

Muzerolle’s team next plans to continue monitoring LRLL 54361 using other facilities including the European Space Agency’s Herschel Space Observatory. The team hopes to eventually obtain more direct measurements of the binary star and its orbit.