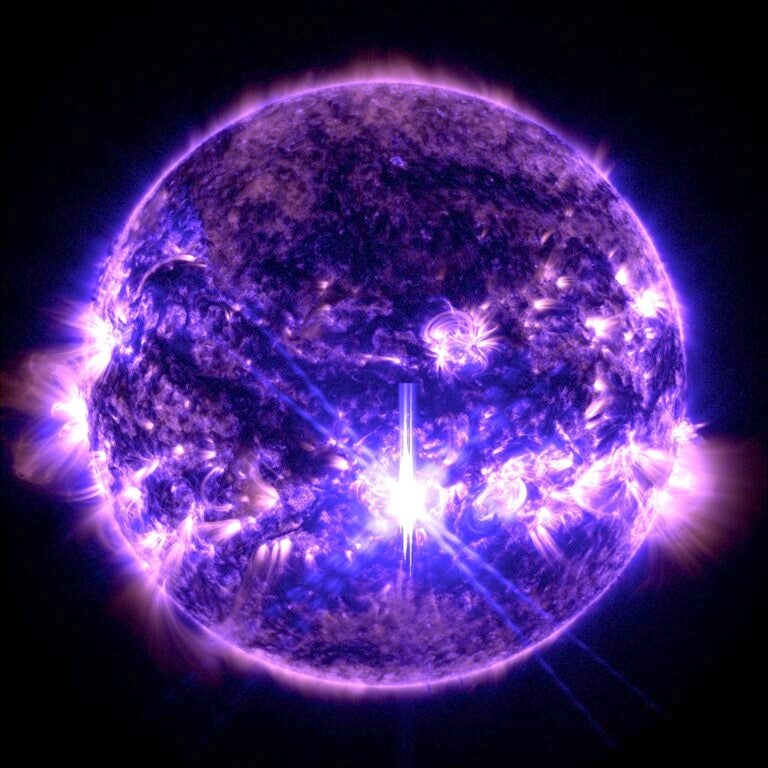

When the science team released its first images in April 2010, SDO’s data exceeded everyone’s hopes and expectations, providing stunningly detailed views of the Sun. In the nearly three years since, SDO’s images have continued to show breathtaking pictures and movies of eruptive events on the Sun. By highlighting different wavelengths of light, scientists can track how material on our star moves. Such movement, in turn, holds clues as to what causes these giant explosions, which, when Earth-directed, can disrupt technology in space.

In its third year of observations, however, SDO has also opened up several new, and unexpected, doors of scientific inquiry. During the last year, scientists spent much time poring over data from comet observations. Comets that travel close to the Sun — known as sun-grazers — have long been observed as they move toward the Sun, but the view was always obscured by our star’s bright light when the comets got too close. SDO has now captured images of two comets as they passed close to the Sun.

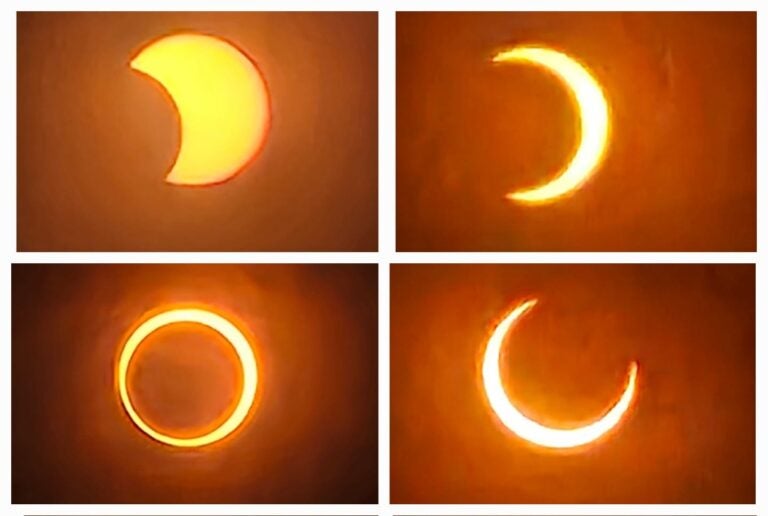

The second highlight of SDO’s third year occurred June 5, 2012, when Venus crossed in front of the Sun as viewed from Earth — an occurrence that will not happen again for more than 100 years. SDO cameras trained on this transit to help calibrate the spacecraft’s instruments and to learn more about Venus’ atmosphere. Since scientists knew the points at which Venus would first touch and later leave the Sun to minute detail, SDO could use this information to make sure its images are oriented to true solar north and calibrate its orientation to within a tenth of a pixel. Scientists also recorded how the Sun’s extreme ultraviolet light traveled through Venus’ atmosphere to learn more about what elements exist around the planet.

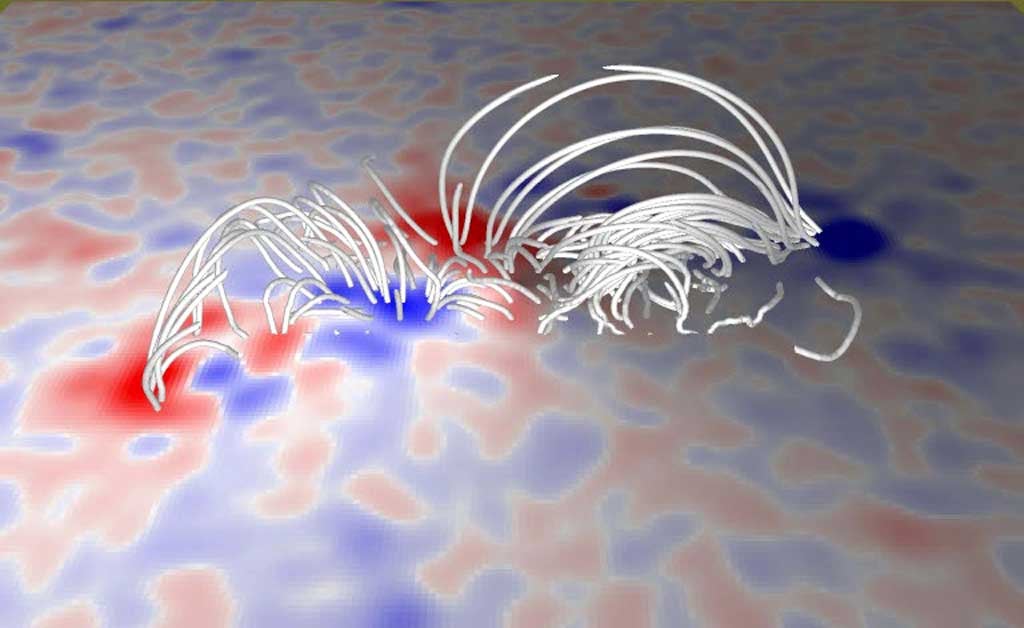

The third new area of SDO data came from the Helioseismic and Magnetic Imager (HMI). The instrument provides real-time maps of magnetic fields of the Sun’s entire surface, showing how strong they are, and, for the first time ever, in which direction they are pointing. Since HMI is providing a type of data never before collected, it has opened up a whole new area of inquiry. Changing and realigning magnetic fields are at the heart of the Sun’s eruptions. Scientists have spent time over the last year to figure out how to best create visual maps from the data, as well as how to interpret them. The HMI images have been affectionately referred to as “hedgehog pictures” since they show spiky quill-like lines pointing out of – or into – the Sun.

Studying such complex magnetic motions inside our star can help scientists understand the complex magnetic fields around the Sun that lead to the eruptions that can cause space weather effects near Earth and other objects in the solar system. Ultimately, research into these constantly changing magnetic fields may lead to advance warning of such dangerous activity, which can send radiation, particles, and magnetic fields toward Earth and sometimes disrupt technology on our and other planets.

The Sun’s greatest hits as captured by the Solar Dynamic Observatory from February 2012 to February 2013. // NASA/GSFC