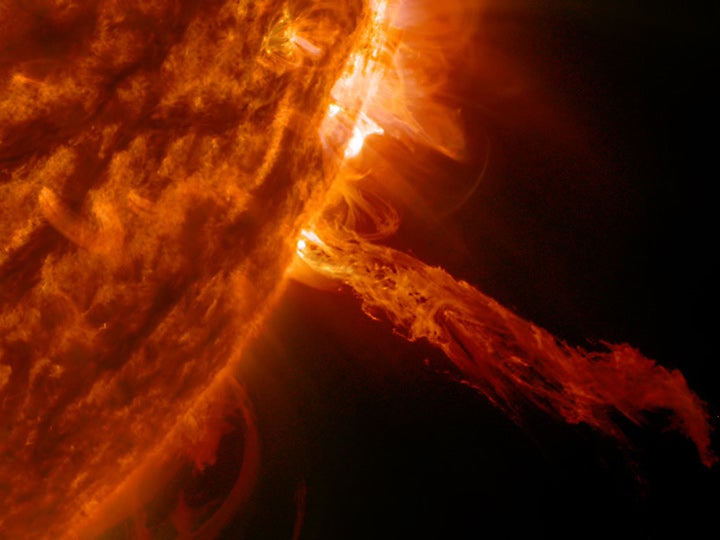

The scientists made the discovery in the course of a study of a spectacular star, VY Canis Majoris (VY CMa), which is a variable star located in the constellation Canis Major the Greater Dog. “VY CMa is not an ordinary star, it is one of the largest stars known, and it is close to the end of its life,” said Tomasz Kaminski from the Max Planck Institute for Radio Astronomy (MPIfR). In fact, with a size of about one to two thousand times that of the Sun, it could extend out to the orbit of Saturn if it were placed in the center of our solar system.

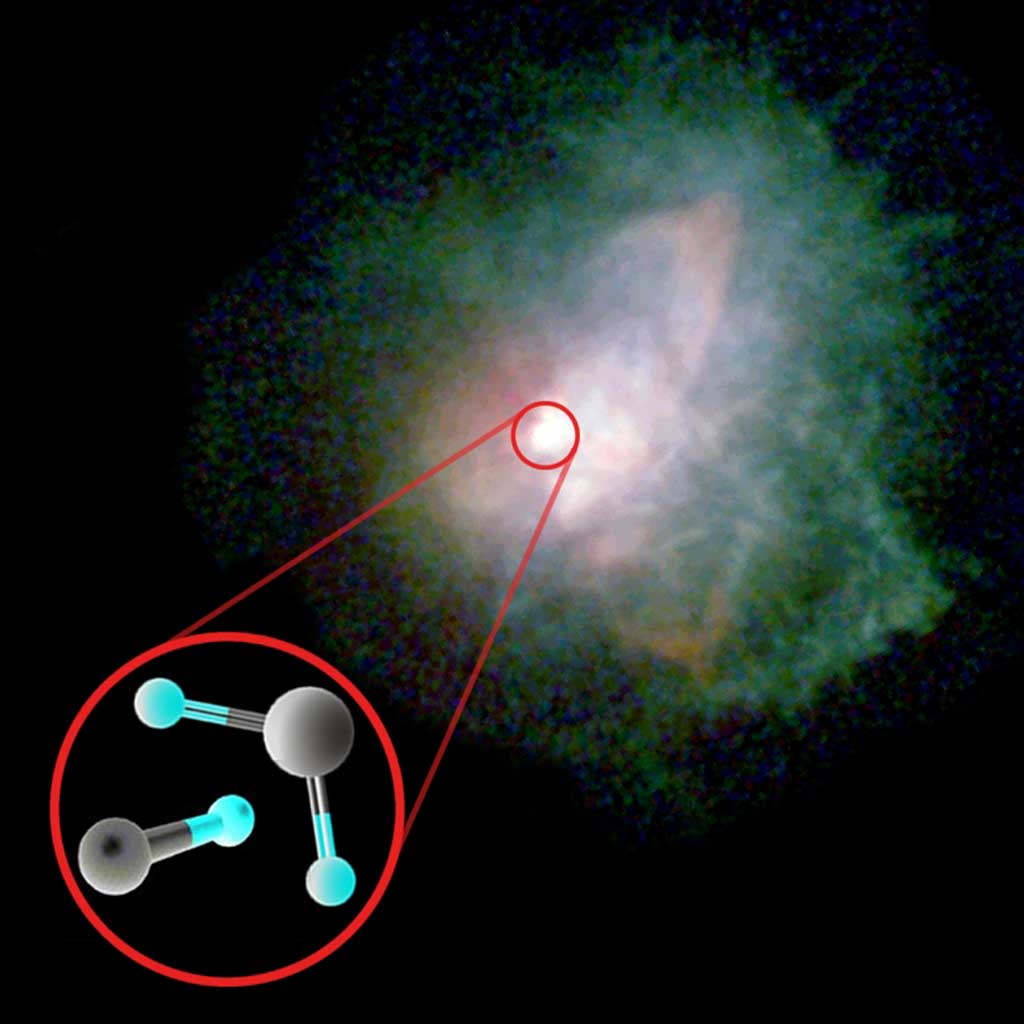

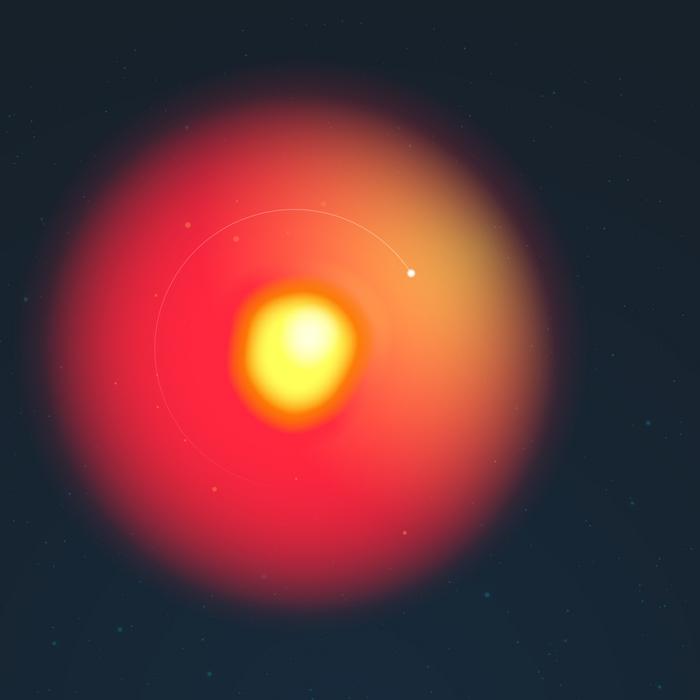

The star ejects large quantities of material, which forms a dusty nebula. The image shows the reflection nebula VY CMa, which is visible because of the small dust particles that form around it that reflect light from the central star. The complexity of this nebula has been puzzling astronomers for decades. It formed as a result of a stellar wind, but scientists don’t understand why it is so far from having a spherical shape. They don’t know what physical process blows the wind, i.e., what lifts the material up from the stellar surface and makes it expand. “The fate of VY CMa is to explode as a supernova, but it is not known exactly when it will happen,” said Karl Menten from MPIfR.

Observations at different wavelengths provide different pieces of information that are characteristic for atomic and molecular gas and from which scientists can derive physical properties of an astronomical object. Each molecule has a characteristic set of lines, something like a “bar code,” that allows astronomers to identify what molecules exist in the nebula. “Emission at short radio wavelengths, in so-called submillimeter waves, is particularly useful for such studies of molecules,” said Sandra Brünken from the University of Cologne. “The identification of molecules is easier, and usually a larger abundance of molecules can be observed than at other parts of the electromagnetic spectrum.”

The research team observed TiO and TiO2 for the first time at radio wavelengths. In fact, titanium dioxide has been seen in space unambiguously for the first time. It is known from everyday life as the main component of the commercially most important white pigment (known by painters as “titanium white”) or as an ingredient in sunscreens. It is also used to color food (coded as E171 on labels). However, stars, especially the coolest of them, are expected to eject large quantities of titanium oxides, which, according to theory, form at relatively high temperatures close to the star. “They tend to cluster together to form dust particles visible in the optical or in the infrared,” said Nimesh Patel from the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics in Cambridge, Massachusetts. “And the catalytic properties of TiO2 may influence the chemical processes taking place on these dust particles, which are very important for forming larger molecules in space,” said Holger Müller from the University of Cologne.

Astronomers have known the absorption features of TiO from spectra in the visible region for more than a hundred years. In fact, these features are used, in part, to classify some types of stars with low surface temperatures (M- and S-type stars). The pulsation of Mira stars, one specific class of variable stars, is thought to be caused by titanium oxide. Mira stars, supergiant variable stars in a late stage of their evolution, are named after their prototype star Mira (the wonderful) in the constellation Cetus the Sea Monster.

The observations of TiO and TiO2 show that the two molecules are easily formed around VY CMa at a location that is more or less as predicted by theory. It seems, however, that some portion of those molecules avoid forming dust and are observable as gas phase species. Another possibility is that the dust is destroyed in the nebula and releases fresh TiO molecules back to the gas. The latter scenario is quite likely as parts of the wind in VY CMa seem to collide with each other.

The new detections at submillimeter wavelengths are particularly important because they allow studying the process of dust formation. Also, at optical wavelengths, the radiation emitted by the molecules is scattered by dust present in the extended nebula that blurs the picture while this effect is negligible at radio wavelengths, allowing for more precise measurements.

The discoveries of TiO and TiO2 in the spectrum of VY CMa have been made with the Submillimeter Array (SMA), a radio interferometer located in Hawaii in the United States. Because the instrument combines eight antennas that work together as one big telescope 226 meters in size, astronomers were able to make observations at unprecedented sensitivity and angular resolution. A confirmation of the new detections was successively made later with the IRAM Plateau de Bure Interferometer (PdBI) located in the French Alps.

The new Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA) in Chile has just been officially opened. “ALMA will allow studies of titanium oxides and other molecules in VY CMa at even better resolution, which makes our discoveries very promising for the future,” said Kaminski.

![Albireo (Beta [β] Cygni) is a classic example of a double star with contrasting colors.](https://www.astronomy.com/uploads/2024/08/Albireo.jpg)