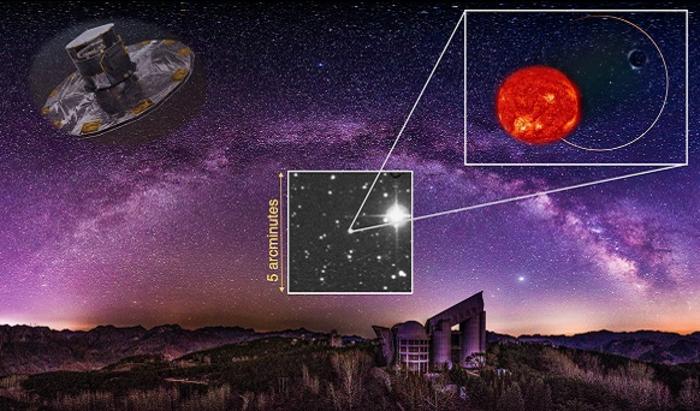

Michael Shull and David Syphers, both from CU, used the Hubble Space Telescope to look at the quasar — the brilliant core of an active galaxy that acted as a “lighthouse” for the observations — to better understand the conditions of the early universe. The scientists studied gaseous material between the telescope and the quasar with a $70 million ultraviolet spectrograph on Hubble designed by a team from CU’s Center for Astrophysics and Space Astronomy.

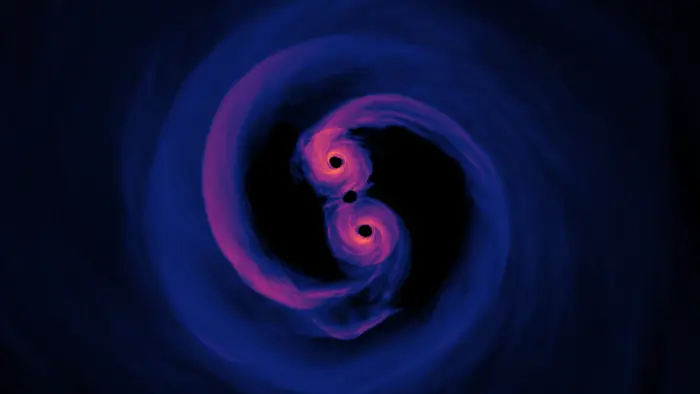

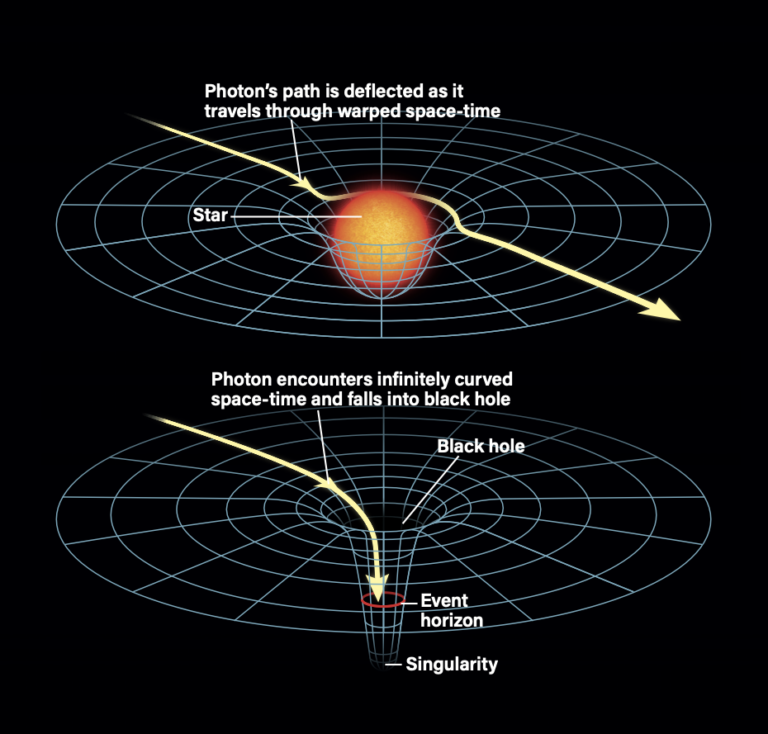

During a time known as the “helium reionization era” some 11 billion years ago, blasts of ionizing radiation from black holes believed to be seated in the cores of quasars stripped electrons from primeval helium atoms, said Shull. The initial ionization that charged up the helium gas in the universe is thought to have occurred sometime shortly after the Big Bang.

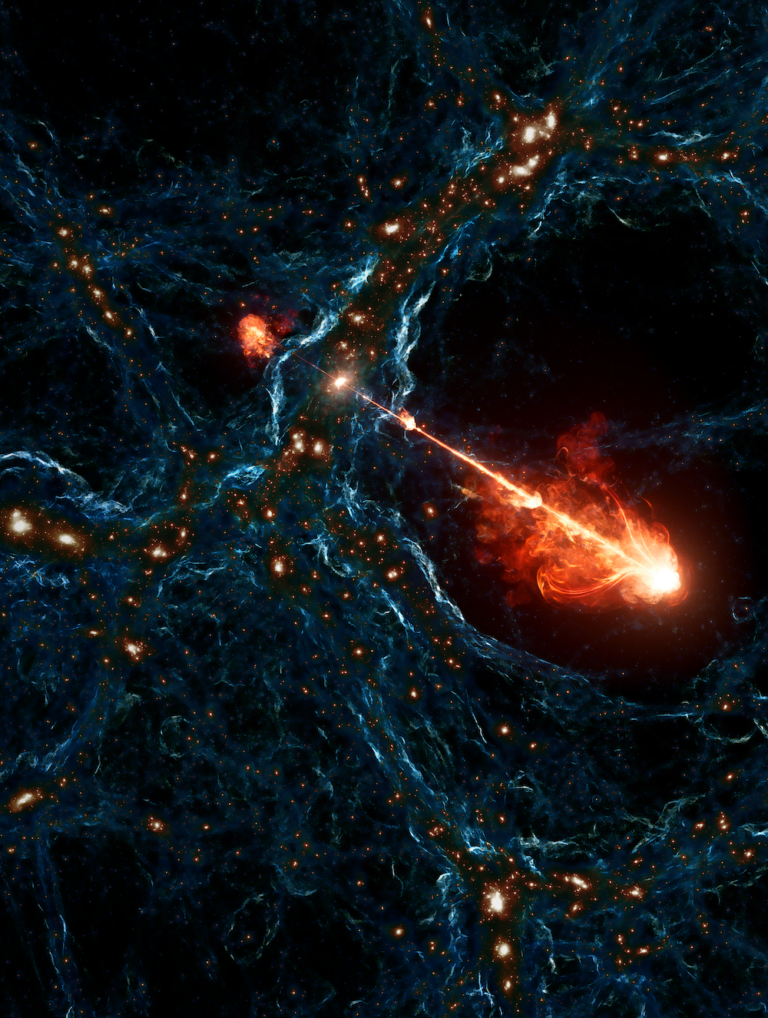

“We think sideline quasars located out of the telescope’s view reionized intergalactic helium gas from different directions, preventing it from gravitationally collapsing and forming new generations of stars,” Shull said. He likened the early universe to a hunk of Swiss cheese, where quasars cleared out zones of neutral helium gas in the intergalactic medium that were then “pierced” by UV observations from the space telescope.

The results of the new study also indicate the helium reionization era of the universe appears to have occurred later than thought. “We initially thought the helium reionization era took place about 12 billion years ago,” said Shull. “But now we think it more likely occurred in the 11 to 10 billion-year range, which was a surprise.”

The Cosmic Origins Spectrograph (COS) used for the quasar observations aboard Hubble was designed to probe the evolution of galaxies, stars, and intergalactic matter. The COS team is led by James Green of CASA and was installed on Hubble by astronauts during its final servicing mission in 2009. COS was built in an industrial partnership between CU and Ball Aerospace & Technologies Corp. of Boulder.

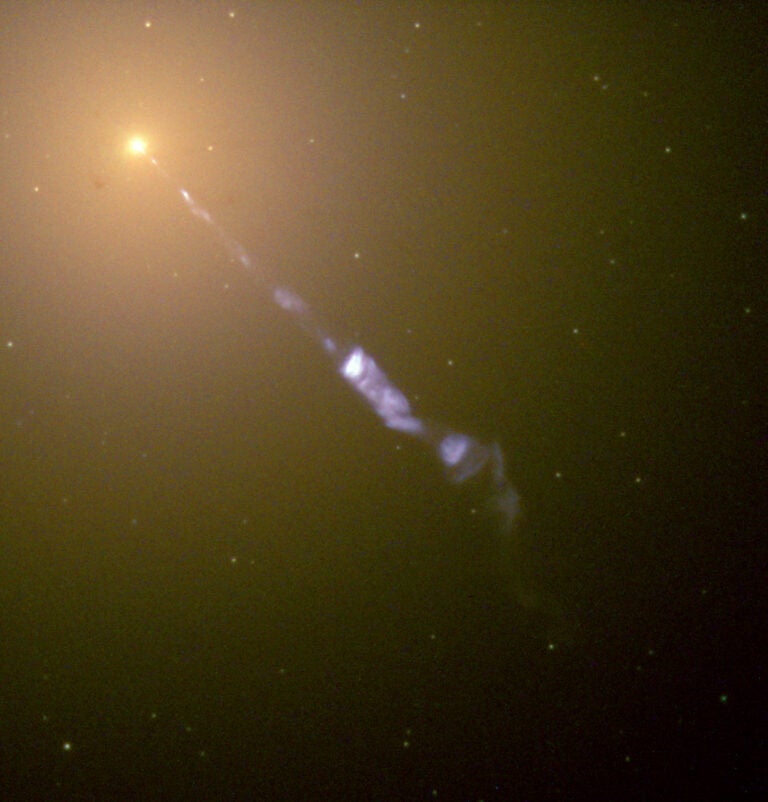

“While there are likely hundreds of millions of quasars in the universe, there are only a handful you can use for a study like this,” said Shull. Quasars are nuclei in the center of active galaxies that have “gone haywire” because of supermassive black holes that gorged themselves in the cores, he said. “For our purposes, they are just a really bright background light that allows us to see to the edge of the universe, like a headlight shining through fog.”

The universe is thought to have begun with the Big Bang that triggered a fireball of searing plasma that expanded and then became cool neutral gas at about 380,000 years, bringing on the “Dark Ages” when there was no light from stars or galaxies, said Shull. The Dark Ages were followed by a period of hydrogen reionization, then the formation of the first galaxies beginning about 13.5 billion years ago. The first galaxies era was followed by the rise of quasars some 2 billion years later, which led to the helium reionization era, he said.

The radiation from the huge quasars heated the gas to 20,000–40,000° Fahrenheit (11,000–22,000° Celsius) in intergalactic realms of the early universe. “It is important to understand that if the helium gas is heated during the epoch of galaxy formation, it makes it harder for protogalaxies to hang on to the bulk of their gas,” said Shull. “In a sense, it’s like intergalactic global warming.”

The team is using COS to probe the “fossil record” of gases in the universe, including a structure known as the “cosmic web” believed to be made of long, narrow filaments of galaxies and intergalactic gas separated by enormous voids. Scientists theorize that a single cosmic web filament may stretch for hundreds of millions of light-years, an eye-popping number considering that a single light-year is about 5.9 trillion miles (9.5 trillion kilometers).

COS breaks light into its individual components — similar to the way raindrops break sunlight into the colors of the rainbow — and reveals information about the temperature, density, velocity, distance, and chemical composition of galaxies, stars, and gas clouds.

For the study, Shull and Syphers used 4.5 hours of data from Hubble observations of the quasar, which has a catalog name of HS1700+6416. While some astronomers define quasars as feeding black holes, “We don’t know if these objects feed once or feed several times,” Shull said. “They are thought to survive only a few million years or perhaps a few hundred million years, a brief blink in time compared to the age of the universe.”

“Our own Milky Way has a dormant black hole in its center,” said Shull. “Who knows? Maybe our Milky Way used to be a quasar.”

The first quasar, short for “quasi-stellar radio source,” was discovered 50 years ago this month by Caltech astronomer Maarten Schmidt. The quasar he observed, 3C 273, is located roughly 2 billion light-years from Earth and is 40 times more luminous than an entire galaxy of 100 billion stars. That quasar is receding from Earth at 15 percent of the speed of light, with related winds blowing millions of miles per hour, said Shull.