The fractured rock, called “Esperance,” provides evidence about an ancient wet environment possibly favorable for life. The mission’s principal investigator, Steve Squyres of Cornell University in Ithaca, New York, said, “Esperance was so important, we committed several weeks to getting this one measurement of it, even though we knew the clock was ticking.”

The mission’s engineers at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in Pasadena, California, had set this week as a deadline for starting a drive toward “Solander Point,” where the team plans to keep Opportunity working during its next martian winter.

“What’s so special about Esperance is that there was enough water not only for reactions that produced clay minerals, but also enough to flush out ions set loose by those reactions so that Opportunity can clearly see the alteration,” said Scott McLennan of the State University of New York in Stony Brook.

This rock’s composition is unlike any other Opportunity has investigated during nine years on Mars — higher in aluminum and silica, lower in calcium and iron.

The next destination, Solander Point, and the area Opportunity is leaving, Cape York, both are segments of the rim of Endeavor Crater, which spans 14 miles (22 kilometers) across. The planned driving route to Solander Point is about 1.4 miles (2.2 kilometers). Cape York has been Opportunity’s home since the rover arrived at the western edge of Endeavor in mid-2011 after a two-year trek from a smaller crater.

“Based on our current solar array dust models, we intend to reach an area of 15° northerly tilt before Opportunity’s sixth martian winter,” said Scott Lever from JPL. “Solander Point gives us that tilt and may allow us to move around quite a bit for winter science observations.”

Northerly tilt increases output from the rover’s solar panels during the southern hemisphere winter. Daily sunshine for Opportunity will reach winter minimum in February 2014. The rover needs to be on a favorable slope well before then.

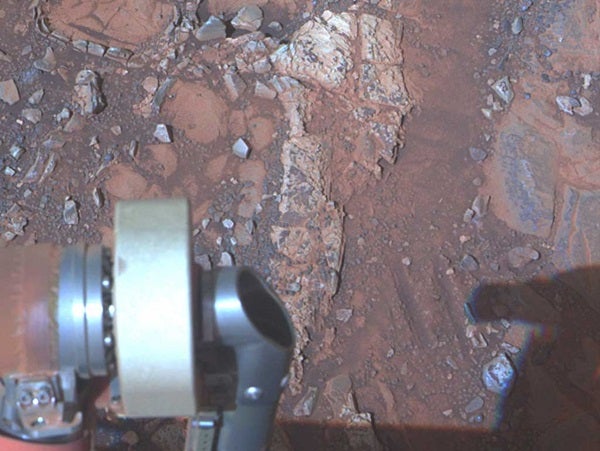

The first drive away from Esperance covered 81.7 feet (24.9 meters) May 14. Three days earlier, Opportunity finished exposing a patch of the rock’s interior with the rock abrasion tool. The team used a camera and spectrometer on the robotic arm to examine Esperance.

The team identified Esperance while exploring a portion of Cape York where the Compact Reconnaissance Spectrometer for Mars (CRISM) on NASA’s Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter had detected a clay mineral. Clays typically form in wet environments that are not harshly acidic. For years, Opportunity had been finding evidence for ancient wet environments that were very acidic. The CRISM findings prompted the rover team to investigate the area where clay had been detected from orbit. There, they found an outcrop called “Whitewater Lake,” containing a small amount of clay from alteration by exposure to water.

“There appears to have been extensive, but weak, alteration of Whitewater Lake but intense alteration of Esperance along fractures that provided conduits for fluid flow,” Squyres said. “Water that moved through fractures during this rock’s history would have provided more favorable conditions for biology than any other wet environment recorded in rocks Opportunity has seen.”