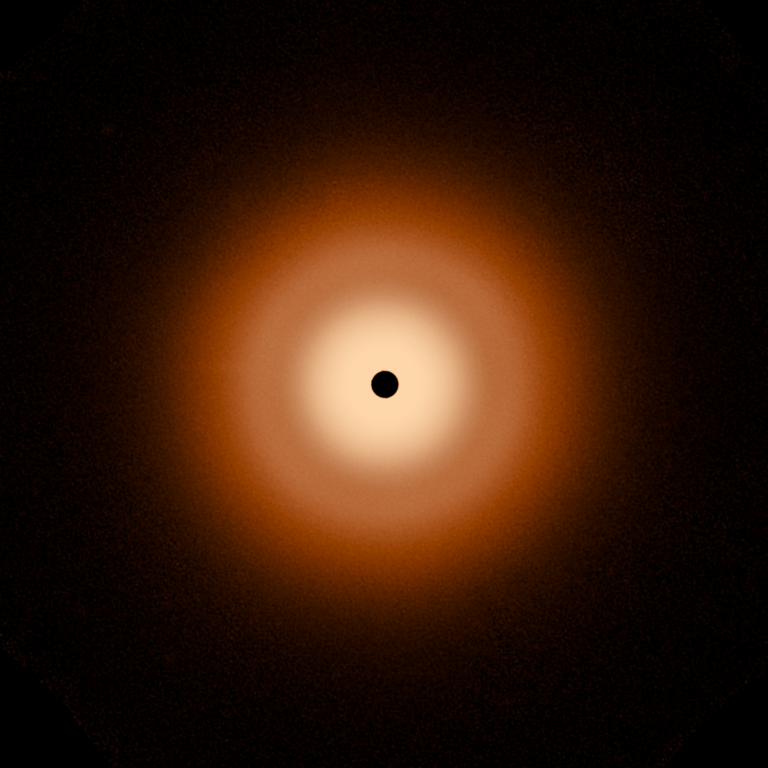

One breakthrough to come in recent years is direct imaging of exoplanets. Ground-based telescopes have begun taking infrared pictures of the planets posing near their stars in family portraits. But to astronomers, a picture is worth even more than a thousand words if its light can be broken apart into a rainbow of different wavelengths.

Those wishes are coming true as researchers are beginning to install infrared cameras on ground-based telescopes equipped with spectrographs. Spectrographs are instruments that spread an object’s light apart, revealing signatures of molecules. Project 1640, partly funded by NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in Pasadena, California, recently accomplished this goal using the Palomar Observatory near San Diego.

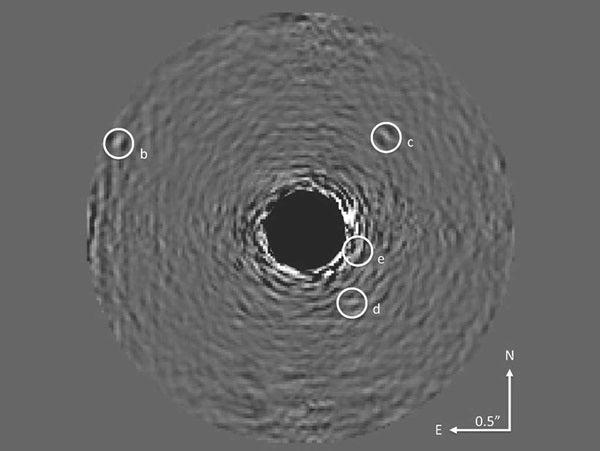

“In just one hour, we were able to get precise composition information about four planets around one overwhelmingly bright star,” said Gautam Vasisht of JPL. “The star is a hundred thousand times as bright as the planets, so we’ve developed ways to remove that starlight and isolate the extremely faint light of the planets.”

Along with ground-based infrared imaging, other strategies for combing through the atmospheres of giant planets are being actively pursued as well. For example, NASA’s Spitzer and Hubble space telescopes monitor planets as they cross in front of their stars, and then disappear behind. NASA’s upcoming James Webb Space Telescope will use a comparable strategy to study the atmospheres of planets only slightly larger than Earth.

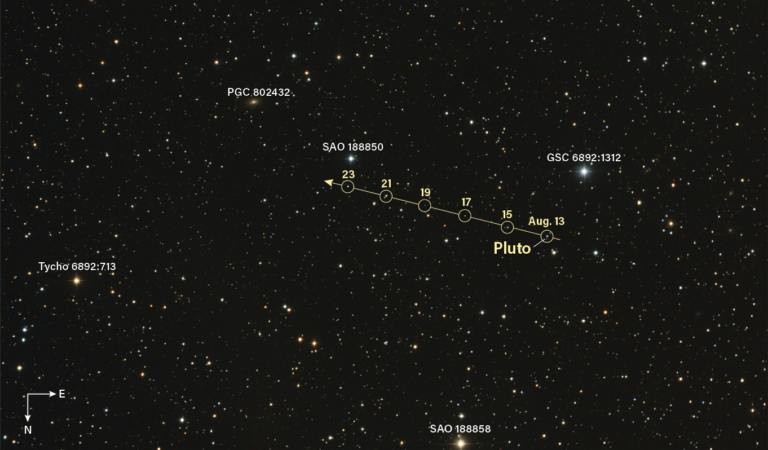

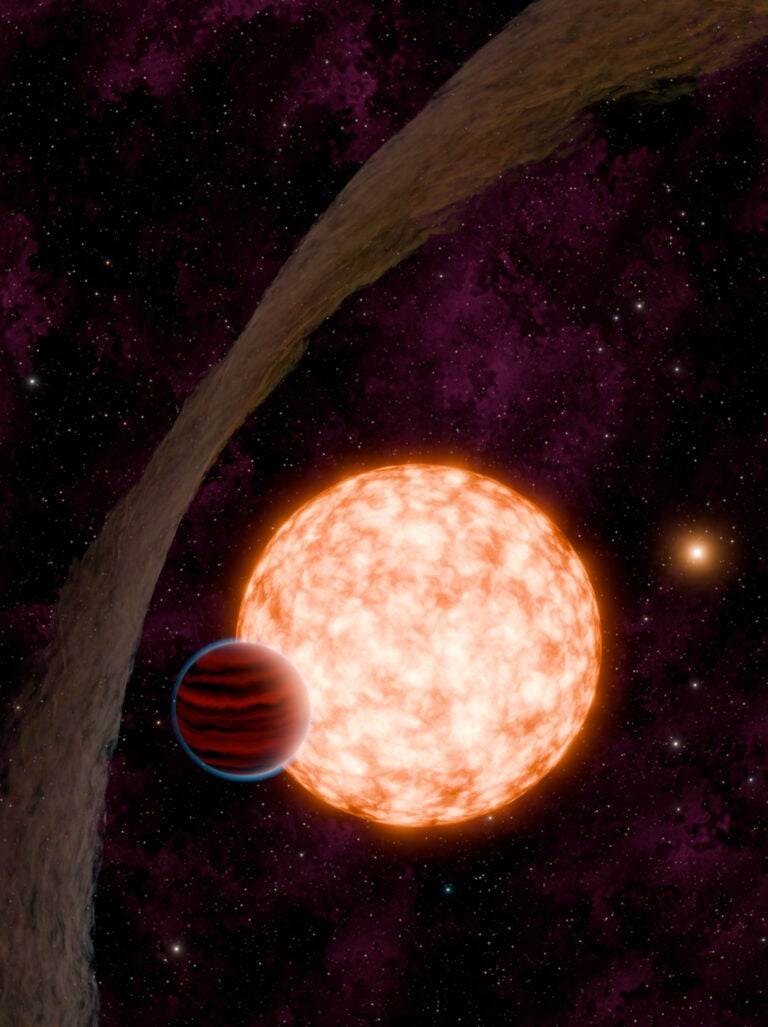

In the new study, the researchers examined HR 8799, a large star orbited by at least four known giant, red planets. Three of the planets were among the first ever directly imaged around a star, thanks to observations from the Gemini and Keck telescopes on Mauna Kea, Hawaii, in 2008. The fourth planet, the closest to the star and the hardest to see, was revealed in images taken by the Keck telescope in 2010.

That alone was a tremendous feat considering that all planet discoveries up until then had been made through indirect means, for example by looking for the wobble of a star induced by the tug of planets.

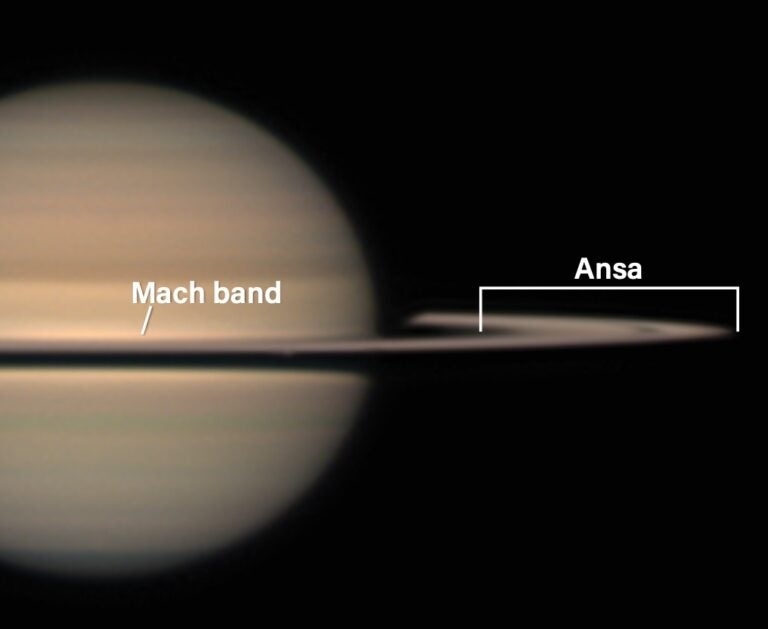

Those images weren’t enough, however, to reveal any information about the planets’ chemical composition. That’s where spectrographs are needed to expose the “fingerprints” of molecules in a planet’s atmosphere. Capturing a distant world’s spectrum requires gathering even more planet light, and that means further blocking the glare of the star.

Project 1640 accomplished this with a collection of instruments, which the team installs on the ground-based telescopes each time they go on “observing runs.” The instrument suite includes a coronagraph to mask out the starlight; an advanced adaptive optics system, which removes the blur of our moving atmosphere by making millions of tiny adjustments to two deformable telescope mirrors; an imaging spectrograph that records 30 images in a rainbow of infrared colors simultaneously; and a state-of-the-art wavefront sensor that further adjusts the mirrors to compensate for scattered starlight.

“It’s like taking a single picture of the Empire State Building from an airplane that reveals a bump on the sidewalk next to it that is as high as an ant,” said Ben R. Oppenheimer, from the Astrophysics Department at the American Museum of Natural History in New York.

Their results revealed that all four planets, though nearly the same in temperature, have different compositions. Some, unexpectedly, do not have methane in them, and there may be hints of ammonia or other compounds that would also be surprising. Further theoretical modeling will help to understand the chemistry of these planets.

Meanwhile, the quest to obtain more and better spectra of exoplanets continues. Other researchers have used the Keck telescope and the Large Binocular Telescope near Tucson, Arizona, to study the emission of individual planets in the HR 8799 system. In addition to the HR 8799 system, only two others have yielded images of exoplanets. The next step is to find more planets ripe for giving up their chemical secrets. Several ground-based telescopes are being prepared for the hunt, including Keck, Gemini, Palomar, and Japan’s Subaru Telescope on Mauna Kea, Hawaii.

Ideally, the researchers want to find young planets that still have enough heat left over from their formation and thus more infrared light for the spectrographs to see. They also want to find planets located far from their stars and out of the blinding starlight. NASA’s infrared Spitzer and Wide-field Infrared Survey Explorer (WISE) missions and its ultraviolet Galaxy Evolution Explorer, now led by the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena, have helped identify candidate young stars that may host planets meeting these criteria.

“We’re looking for super-Jupiter planets located far away from their star,” said Vasisht. “As our technique develops, we hope to be able to acquire molecular compositions of smaller and slightly older gas planets.”

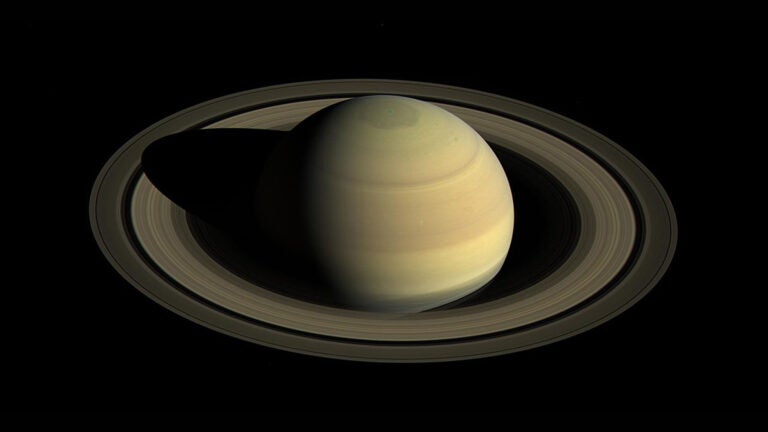

Still lower-mass planets, down to the size of Saturn, will be targets for imaging studies by the James Webb Space Telescope.

“Rocky Earth-like planets are too small and close to their stars for the current technology or even for James Webb to detect. The feat of cracking the chemical compositions of true Earth analogs will come from a future space mission such as the proposed Terrestrial Planet Finder,” said Charles Beichman from the NASA’s Exoplanet Science Institute at Caltech.

Though the larger gas planets are not hospitable to life, the current studies are teaching astronomers how the smaller rocky ones form.

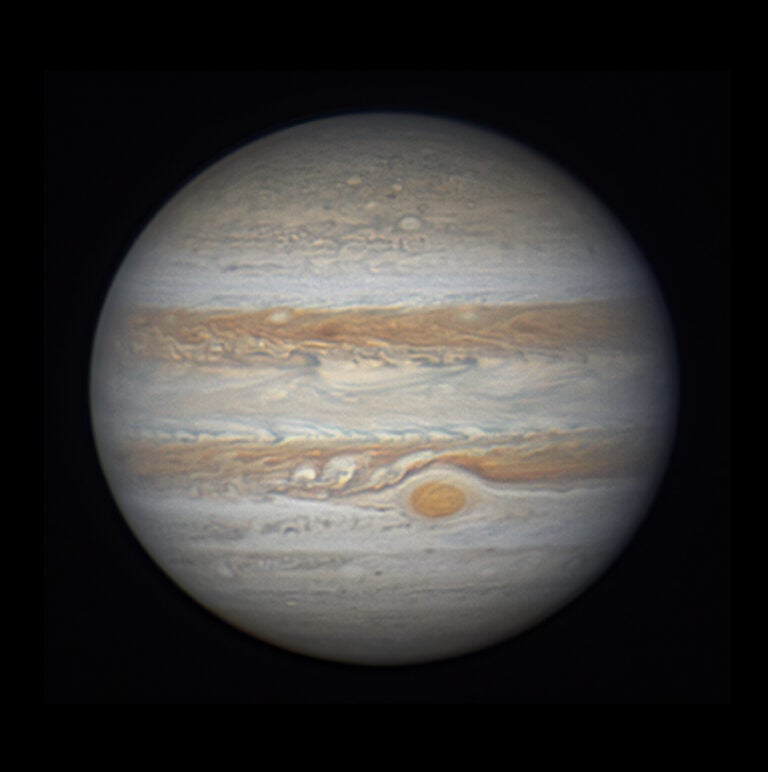

“The outer giant planets dictate the fate of rocky ones like Earth. Giant planets can migrate in toward a star and, in the process, tug the smaller rocky planets around or even kick them out of the system. We’re looking at hot Jupiters before they migrate in and hope to understand more about how and when they might influence the destiny of the rocky inner planets,” said Vasisht.