“With the huge amount of methane in its atmosphere, Titan smog is like L.A. smog on steroids,” said Scott Edgington from NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California. “These new papers using Cassini data shed light on how the heavy complex hydrocarbon molecules that make up Titan’s smog came to form out of the simpler molecules in the atmosphere. Now that they have been identified, the longevity of Cassini’s mission will make it possible to study their variation with Titan seasons.”

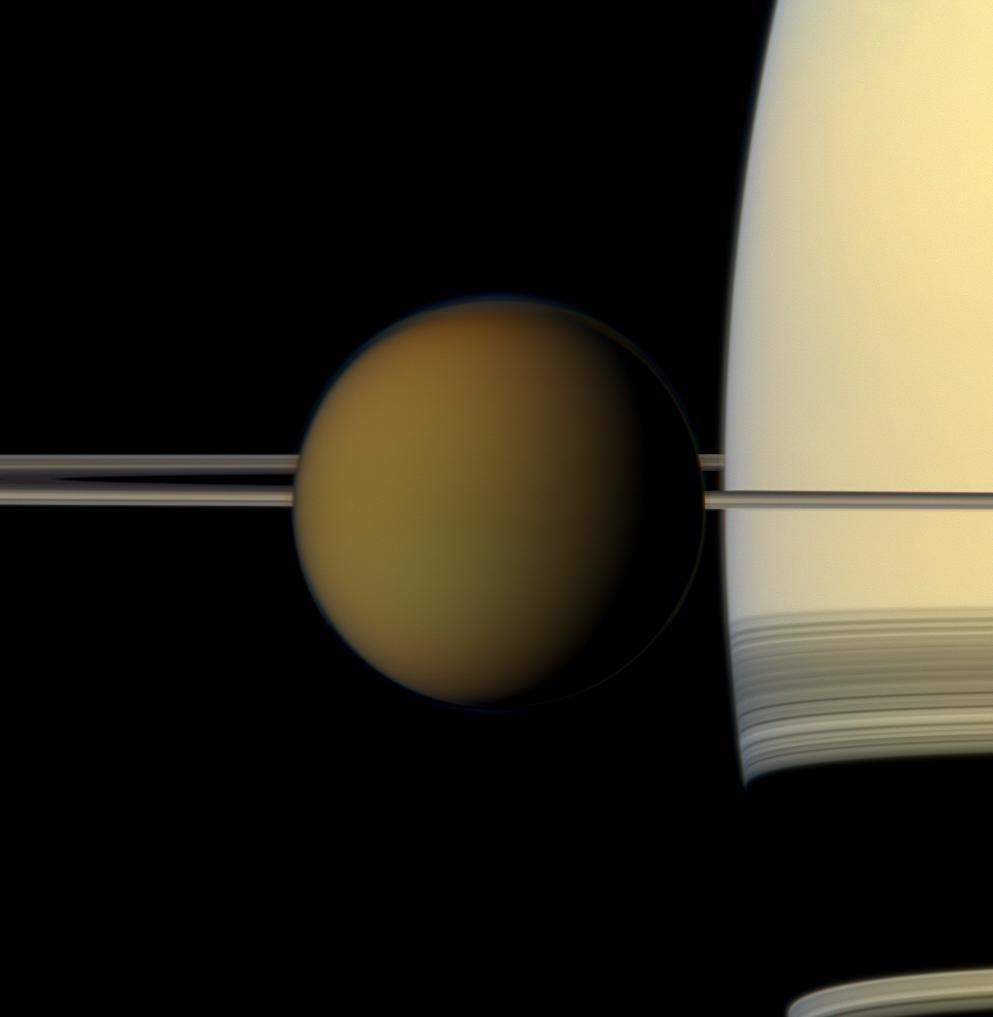

Of all the bodies in the solar system, Saturn’s largest moon, Titan, has the atmosphere most resembling that of Earth. Like that of our planet, Titan’s atmosphere is largely composed of molecular nitrogen. Unlike Earth’s atmosphere, however, Titan’s contains only small traces of oxygen and water. Another molecule, methane, plays a similar role to that of water in Earth’s atmosphere and makes up about 2 percent of Titan’s atmosphere. Scientists have speculated that the atmosphere of this moon may resemble that of our planet in its early days before primitive living organisms enriched it with oxygen via photosynthesis.

When sunlight or highly energetic particles from Saturn’s magnetic bubble hit the layers of Titan’s atmosphere above about 600 miles (1,000 kilometers), the nitrogen and methane molecules are broken up. This results in the formation of massive positive ions and electrons, which trigger a chain of chemical reactions, producing a variety of hydrocarbons — a wide range of which have been detected in Titan’s atmosphere. These reactions eventually lead to the production of carbon-based aerosols, large aggregates of atoms and molecules that are found in the lower layers of the haze that enshrouds Titan well below 300 miles (500 km). The process is similar to Earth, where smog starts with sunlight breaking up hydrocarbons that are emitted into the air. The resulting pieces recombine to form more complex molecules.

Aerosols in Titan’s lower haze have been studied using data from the descent of the European Space Agency’s Huygens probe, which reached the surface in 2005, but their origin remained unclear. New studies analyzing data from Cassini’s visual and infrared mapping spectrometer (VIMS) gathered in July and August 2007 might solve the problem. One new study of Titan’s upper atmosphere describes the detection of the PAHs, which are large carbon-based molecules that form from the aggregation of smaller hydrocarbons.

“We can finally confirm that PAHs play a major role in the production of Titan’s lower haze and that the chemical reactions leading to the formation of the haze start high up in the atmosphere,” said Manuel López-Puertas from the Astrophysics Institute of Andalucia in Granada, Spain. “This finding is surprising: We had long suspected that PAHs and aerosols were linked in Titan’s atmosphere but didn’t expect we could prove this with current instruments.”

The team of scientists had been studying the emission from various molecules in Titan’s atmosphere when they stumbled upon a peculiar feature in the data. One of the characteristic lines in the spectrum — from methane emissions — had a slightly anomalous shape, and the scientists suspected it was hiding something.

Bianca Maria Dinelli from the Institute of Atmospheric Sciences and Climate in Bologna, Italy, and her colleagues conducted a painstaking investigation to identify the chemical species responsible for the anomaly. The additional signal was found only during daytime, so it clearly had something to do with solar irradiation.

“The central wavelength of this signal, about 3.28 microns, is typical for aromatic compounds — hydrocarbon molecules in which the carbon atoms are bound in ring-like structures,” said Dinelli.

The scientists tested whether the unidentified emission could be produced by benzene, the simplest aromatic compound consisting of one ring only, which had been detected earlier in Titan’s atmosphere. However, the relatively low abundances of benzene are not sufficient to explain the emission that had been observed.

After they ruled out benzene, the scientists tried to reproduce the observed emission with the more complex PAHs. They checked their data against the NASA Ames PAH Infrared Spectral Data Base. And they were successful: The data can be explained as emission by a mixture of many different PAHs, which contain an average of 34 carbon atoms and about 10 rings each.

“PAHs are very efficient in absorbing ultraviolet radiation from the Sun, redistributing the energy within the molecule, and finally emitting it at infrared wavelengths,” said Alberto Adriani from the Institute for Space Astrophysics and Planetology at Italy’s National Institute for Astrophysics in Rome. He is part of the Cassini-VIMS co-investigators team and started this investigation. He manages the team that collected and processed VIMS data.

These hydrocarbons also are peculiarly capable of sending out profuse amounts of infrared radiation even in the rarefied environment of Titan’s upper atmosphere, where the collisions between molecules are not frequent. The molecules are themselves an intermediate product, generated when radiation from the Sun ionizes smaller molecules in the upper atmosphere of Titan that then coagulate and sink.