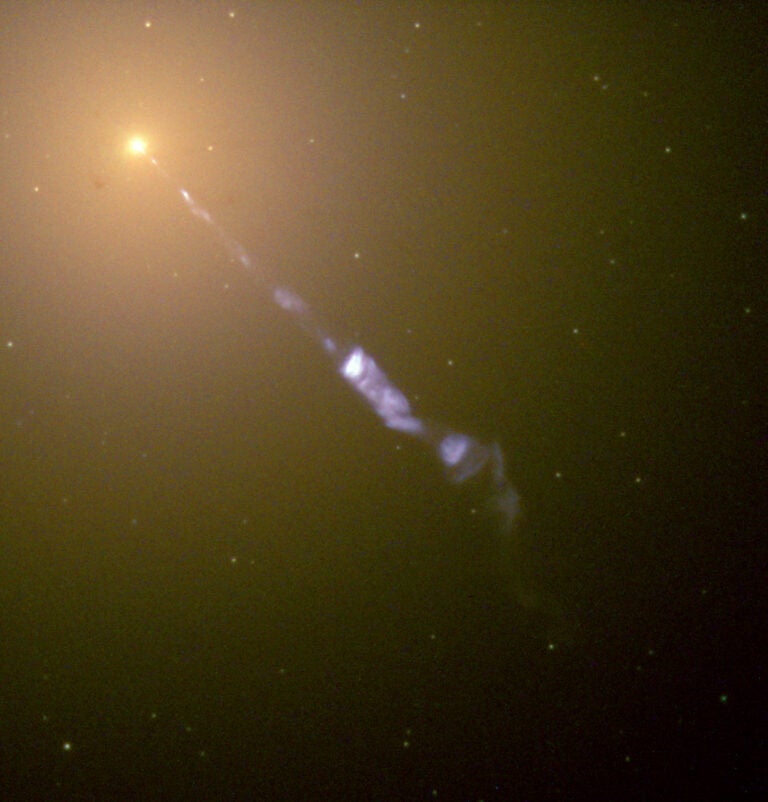

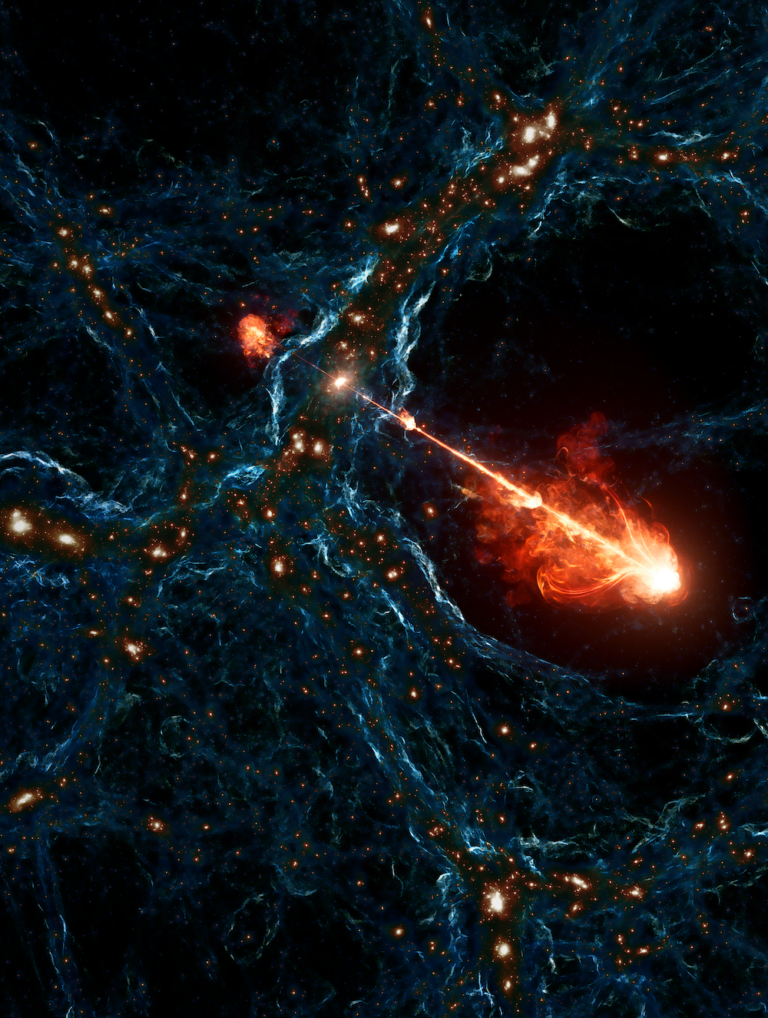

Over the last 20 years, astronomers have found that almost all galaxies have a huge black hole at their center. Some of these black holes are growing by drawing in matter from their surroundings, creating in the process the most energetic objects in the universe — active galactic nuclei (AGN). The central regions of these brilliant powerhouses are ringed by doughnuts of cosmic dust dragged from the surrounding space, similar to how water forms a small whirlpool around the plughole of a sink. It was thought that most of the strong infrared radiation coming from AGN originated in these doughnuts.

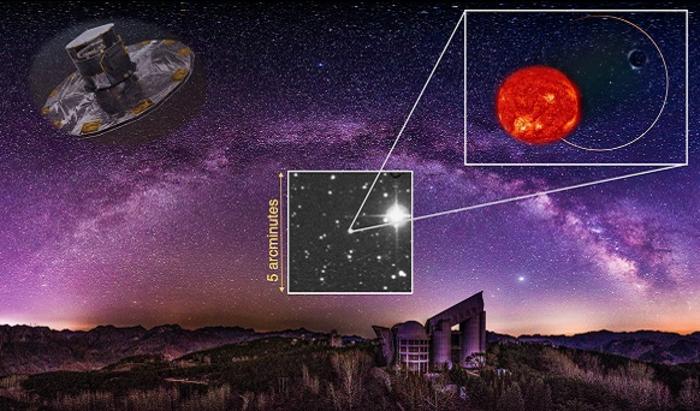

But new observations of a nearby active galaxy called NGC 3783, harnessing the power of the VLTI at ESO’s Paranal Observatory in Chile, have given a team of astronomers a surprise. Although the hot dust — at some 1300°–1800° Fahrenheit (700°–1000° Celsius) — is indeed in a torus as expected, they found huge amounts of cooler dust above and below this main torus.

“This is the first time we’ve been able to combine detailed mid-infrared observations of the cool room-temperature dust around an AGN with similarly detailed observations of the very hot dust,” said Sebastian Hönig from the University of California, Santa Barbara, and Christian-Albrechts-University of Kiel, Germany. “This also represents the largest set of infrared interferometry for an AGN published yet.”

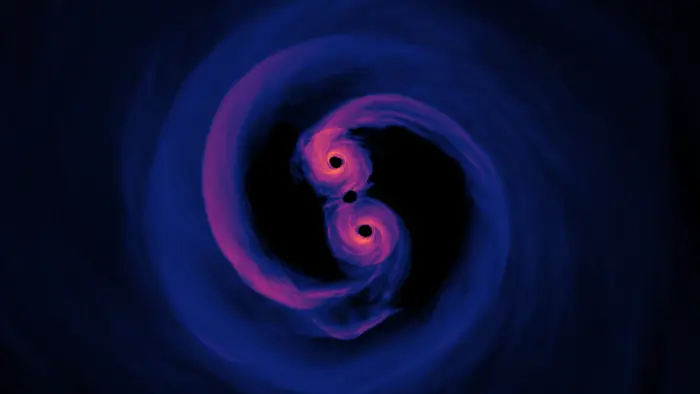

The newly discovered dust forms a cool wind streaming outward from the black hole. This wind must play an important role in the complex relationship between the black hole and its environment. The black hole feeds its insatiable appetite from the surrounding material, but the intense radiation this produces also seems to be blowing the material away. It is still unclear how these two processes work together and allow supermassive black holes to grow and evolve within galaxies, but the presence of a dusty wind adds a new piece to this picture.

In order to investigate the central regions of NGC 3783, the astronomers needed to use the combined power of the Unit Telescopes of ESO’s Very Large Telescope. Using these units together forms an interferometer that can obtain a resolution equivalent to that of a 130-meter telescope.

“By combining the world-class sensitivity of the large mirrors of the VLT with interferometry, we are able to collect enough light to observe faint objects,” said Gerd Weigelt from the Max Planck Institute for Radio Astronomy in Bonn, Germany. “This lets us study a region as small as the distance from our Sun to its closest neighboring star in a galaxy tens of millions of light-years away. No other optical or infrared system in the world is currently capable of this.”

These new observations may lead to a paradigm shift in the understanding of AGN. They are direct evidence that dust is being pushed out by the intense radiation. Models of how the dust is distributed and how supermassive black holes grow and evolve must now take into account this newly discovered effect.

“I am now really looking forward to MATISSE, which will allow us to combine all four VLT Unit Telescopes at once and observe simultaneously in the near- and mid-infrared, giving us much more detailed data,” said Hönig. MATISSE, a second-generation instrument for the VLTI, is currently under construction.