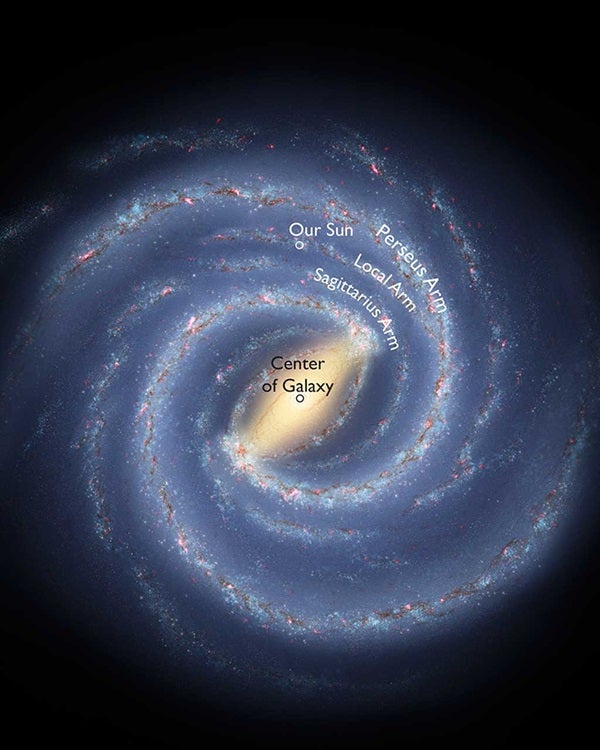

“Our new evidence suggests that the Local Arm should appear as a prominent feature of the Milky Way,” said Alberto Sanna of the Max Planck Institute for Radio Astronomy in Germany.

Determining the structure of our own galaxy has been a long-standing problem for astronomers because we are inside it. In order to map the Milky Way, scientists need to accurately measure the distances to objects within the galaxy. Measuring cosmic distances, however, also has been a difficult task, leading to large uncertainties. The result is that, while astronomers agree that our galaxy has a spiral structure, there are disagreements on how many arms it has and on their specific locations.

To help resolve this problem, researchers turned to the VLBA and its ability to make the most accurate measurements of positions in the sky available to astronomers. The VLBA’s capabilities allowed the astronomers to use a technique that yields accurate distance measurements unambiguously through simple trigonometry.

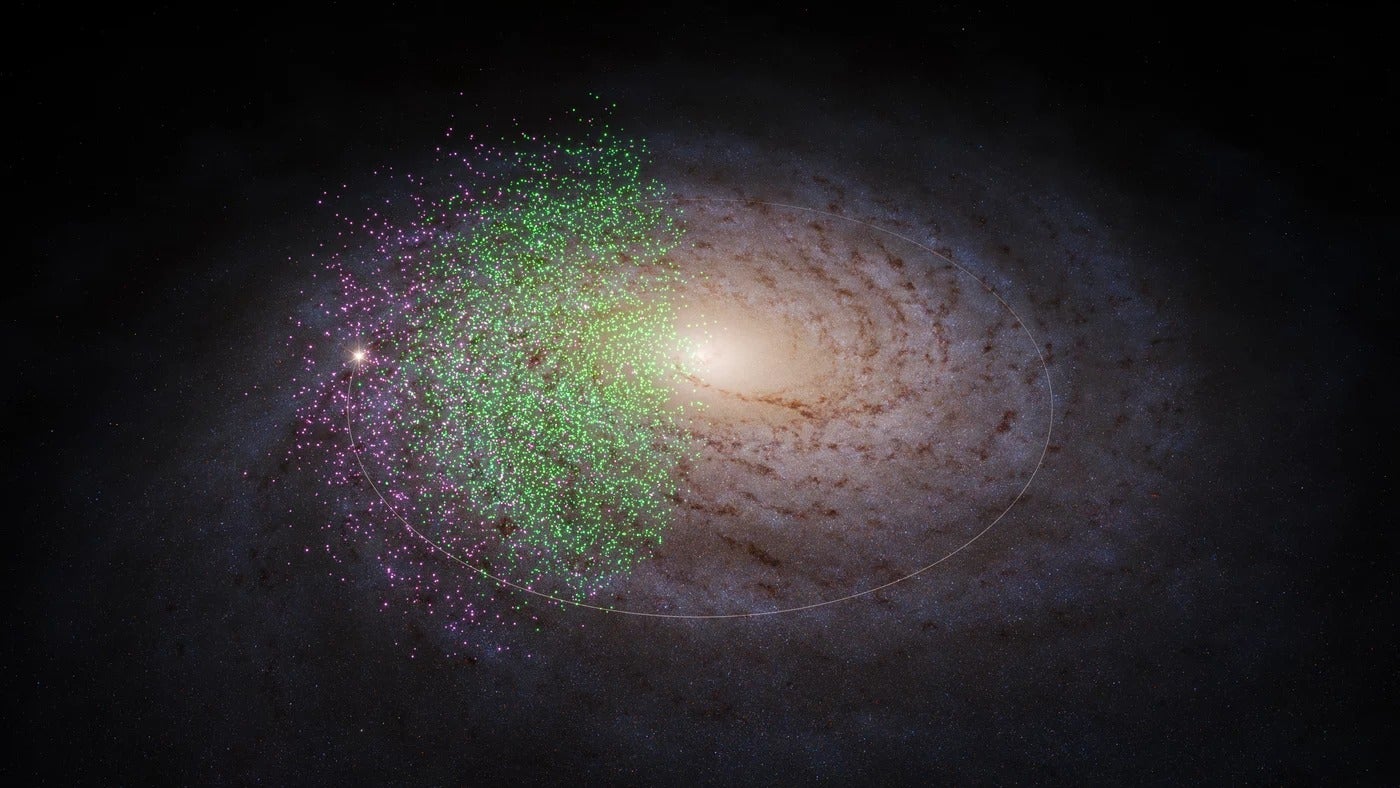

The astronomers used this method to measure the distances to star-forming regions in the Milky Way where water and methanol molecules are boosting radio waves in the same fashion that a laser boosts light waves. These objects, called masers, are like lighthouses for the radio telescopes. The VLBA observations, carried out from 2008 to 2012, produced accurate distance measurements to the masers and also allowed the scientists to track their motion through space.

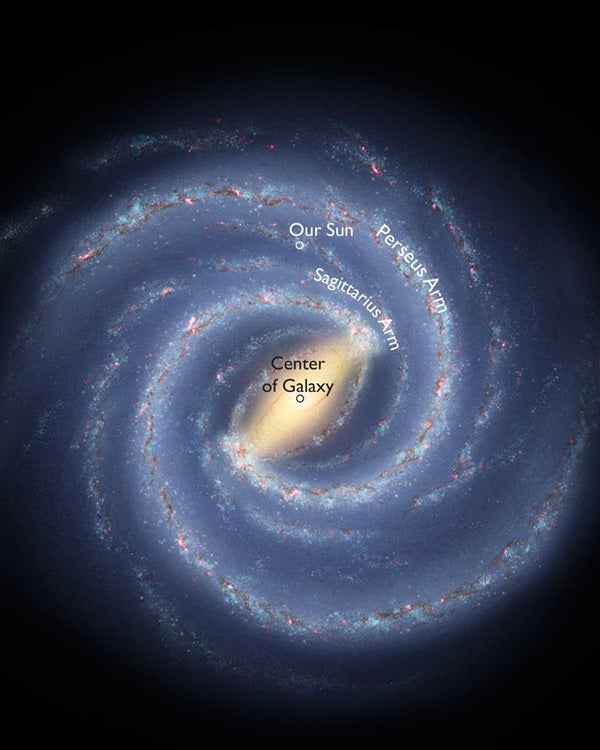

A striking result was an upgrade to the status of the Local Arm within which our solar system resides. We are between two major spiral arms of the galaxy, the Sagittarius Arm and the Perseus Arm. The Sagittarius Arm is closer to the galactic center, and the Perseus Arm is farther out in the galaxy. The Local Arm previously was thought to be a minor structure, a “spur” between the two longer arms.

“Based on both the distances and the space motions we measured, our Local Arm is not a spur. It is a major structure, maybe a branch of the Perseus Arm, or possibly an independent arm segment,” Sanna said.

The scientists also presented new details about the distribution of star formation in the Perseus Arm and about the more distant Outer Arm, which encompasses a warp in our galaxy.

The new observations are part of an ongoing project called the Bar and Spiral Structure Legacy (BeSSeL) survey, a major effort to map the Milky Way using the VLBA. The acronym honors Friedrich Wilhelm Bessel, the German astronomer who made the first accurate measurement of a star’s parallax in 1838.