Now, a new study using data from NASA’s Kepler space telescope shows that hot Jupiters, despite their close-in orbits, are not regularly consumed by their stars. Instead, the planets remain in fairly stable orbits for billions of years until the day comes when they may ultimately get eaten.

“Eventually, all hot Jupiters get closer and closer to their stars, but in this study, we are showing that this process stops before the stars get too close,” said Peter Plavchan of NASA’s Exoplanet Science Institute at the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena. “The planets mostly stabilize once their orbits become circular, whipping around their stars every few days.”

The study is the first to demonstrate how the hot Jupiter planets halt their inward march on stars. Gravitational, or tidal, forces of a star circularize and stabilize a planet’s orbit; when its orbit finally become circular, the migration ceases.

“When only a few hot Jupiters were known, several models could explain the observations,” said Jack Lissauer from NASA’s Ames Research Center in Moffet Field, California. “But finding trends in populations of these planets shows that tides, in combination with gravitational forces by often unseen planetary and stellar companions, can bring these giant planets close to their host stars.”

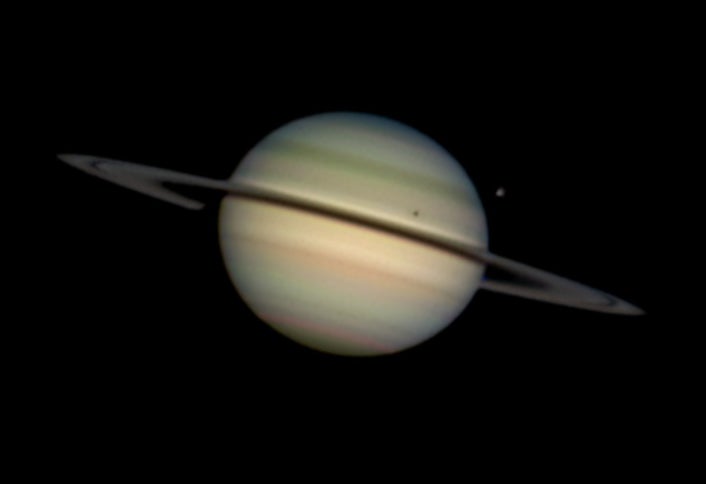

Hot Jupiters are giant balls of gas that resemble Jupiter in mass and composition. They don’t begin life under the glare of a sun, but form in the chilly outer reaches, as Jupiter did in our solar system. Ultimately, the hot Jupiter planets head in toward their stars, a relatively rare process still poorly understood.

The new study answers questions about the end of the hot Jupiters’ travels, revealing what put the brakes on their migration. Previously, there were a handful of theories explaining how this might occur. One theory proposed that the star’s magnetic field prevented the planets from going any farther. When a star is young, a planet-forming disk of material surrounds it. The material falls into the star — a process astronomers call accretion — but when it hits the magnetic bubble around it, called the magnetosphere, the material travels up and around the bubble, landing on the star from the top and bottom. This bubble could be halting migrating planets, so the theory went.

Another theory held that the planets stopped marching forward when they hit the end of the dusty portion of the planet-forming disk.

“This theory basically said that the dust road a planet travels on ends before the planet falls all the way into the star,” said Chris Bilinski of the University of Arizona in Tucson. “A gap forms between the star and the inner edge of its dusty disk where the planets are thought to stop their migration.”

And yet a third theory, the one the researchers found to be correct, proposed that a migrating planet stops once the star’s tidal forces have completed their job of circularizing its orbit.

To test these and other scenarios, the scientists looked at 126 confirmed planets and more than 2,300 candidates. The majority of the candidates and some of the known planets were identified via NASA’s Kepler mission. Kepler has found planets of all sizes and types, including rocky ones that orbit where temperatures are warm enough for liquid water.

The scientists looked at how the planets’ distance from their stars varied depending on the mass of the star. It turns out that the various theories explaining what stops migrating planets differ in their predictions of how the mass of a star affects the orbit of the planet. The “tidal forces” theory predicted that the hot Jupiters of more massive stars would orbit farther out, on average.

The survey results matched the “tidal forces” theory and even showed more of a correlation between massive stars and farther-out orbits than predicted.

This may be the end of the road for the mystery of what halts migrating planets, but the journey itself still poses many questions. As gas giants voyage inward, it is thought that they sometimes kick smaller rocky planets out of the way and with them any chance of life evolving. Lucky for us, our Jupiter did not voyage toward the Sun, and Earth was left in peace. More studies like this one will help explain these and other secrets of planetary migration.