The explosion would have been visible from Earth a little more than a hundred years ago if it had not been heavily obscured by dust and gas. Its likely location is about 28,000 light-years from Earth near the center of the Milky Way. A long observation equivalent to more than 11 days of observations of its debris field, now known as the supernova remnant G1.9+0.3, with NASA’s Chandra X-ray Observatory is providing new details about this important event.

The source of G1.9+0.3 was most likely a white dwarf star that underwent a thermonuclear detonation and was destroyed after merging with another white dwarf or pulling material from an orbiting companion star. This is a particular class of supernova explosions, known as type Ia, that are used as distance indicators in cosmology because they are so consistent in brightness and incredibly luminous.

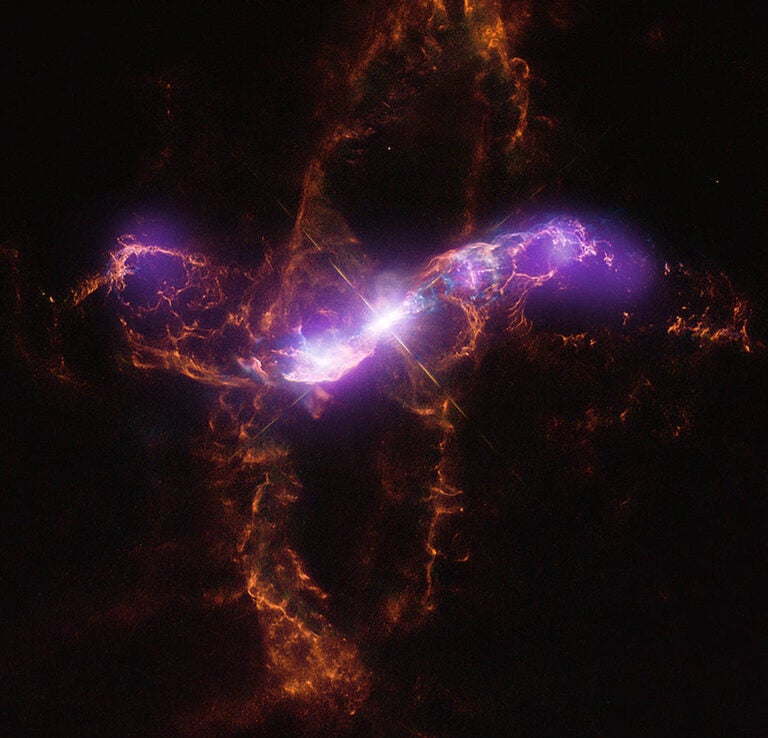

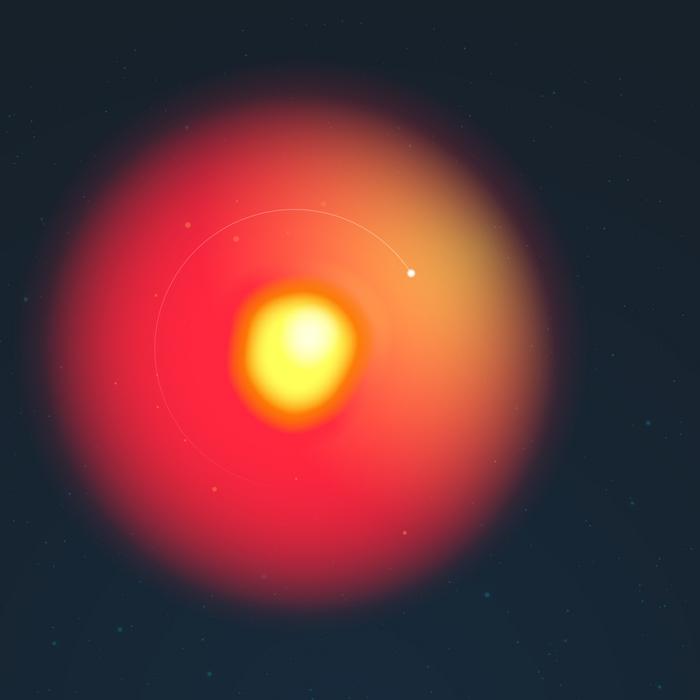

The explosion ejected stellar debris at high velocities, creating the supernova remnant that is seen today by Chandra and other telescopes. This new image is a composite from Chandra where low-energy X-rays are red, intermediate energies are green, and higher-energy ones are blue. Also shown are optical data from the Digitized Sky Survey, with stars appearing in white. The new Chandra data, obtained in 2011, reveal that G1.9+0.3 has several remarkable properties.

The Chandra data show that most of the X-ray emission is “synchrotron radiation” produced by extremely energetic electrons accelerated in the rapidly expanding blast wave of the supernova. This emission gives information about the origin of cosmic rays — energetic particles that constantly strike the Earth’s atmosphere — but not much information about type Ia supernovae.

In addition, some of the X-ray emission comes from elements produced in the supernova, providing clues to the nature of the explosion. The long Chandra observation was required to dig out those clues.

Most type Ia supernova remnants are symmetrical in shape, with debris evenly distributed in all directions. However, G1.9+0.3 exhibits an extremely asymmetric pattern. The strongest X-ray emission from elements like silicon, sulfur, and iron is found in the northern part of the remnant.

Another exceptional feature of this remnant is that iron, which is expected to form deep in the doomed star’s interior and move relatively slowly, is found far from the center and is moving at extremely high speeds of over 3.8 million mph (6.1 million km/h). The iron is mixed with lighter elements expected to form further out in the star.

Because of the uneven distribution of the remnant’s debris and their extreme velocities, the researchers conclude that the original supernova explosion also had very unusual properties. That is, the explosion itself must have been highly nonuniform and unusually energetic.

By comparing the properties of the remnant with theoretical models, the researchers found hints about the explosion mechanism. Their favorite concept for what happened in G1.9+0.3 is a “delayed detonation,” where the explosion occurs in two different phases. First, nuclear reactions occur in a slowly expanding wavefront, producing iron and similar elements. The energy from these reactions causes the star to expand, changing its density and allowing a much faster-moving detonation front of nuclear reactions to occur.

If the explosion was highly asymmetric, then there should be large variations in expansion rate in different parts of the remnant. These should be measurable with future observations with X-rays using Chandra and radio waves with the National Science Foundation’s Karl G. Jansky Very Large Array.

Observations of G1.9+0.3 allow astronomers a special close-up view of a young supernova remnant and its rapidly changing debris. Many of these changes are driven by the radioactive decay of elements ejected in the explosion. For example, a large amount of antimatter should have formed after the explosion by radioactive decay of cobalt. Based on the estimated mass of iron, which is formed by radioactive decay of nickel to cobalt to iron, over a hundred million trillion pounds of positrons, the antimatter counterpart to electrons, should have formed. However, nearly all of these positrons should have combined with electrons and been destroyed, so no direct observational signature of this antimatter should remain.