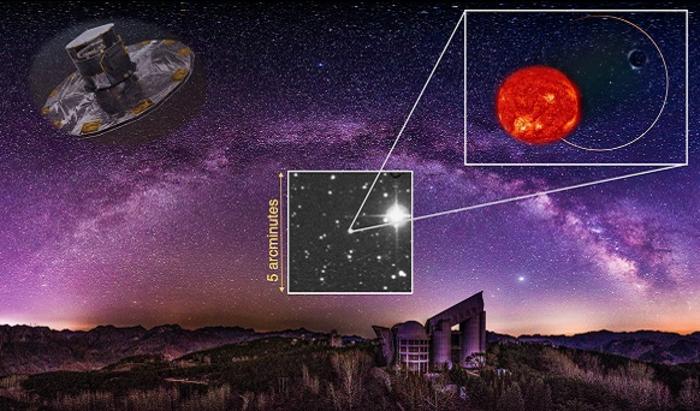

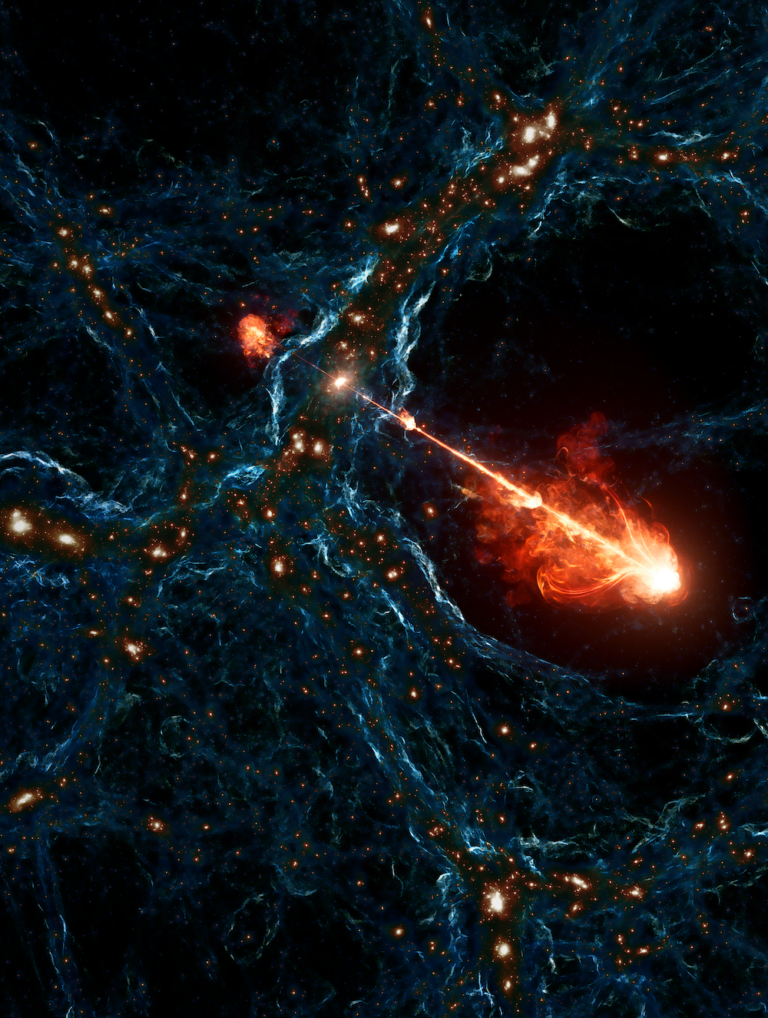

The international research team observed four fast radio bursts whose brightness and distances suggest they come from cosmological distances when the universe was just half its current age.

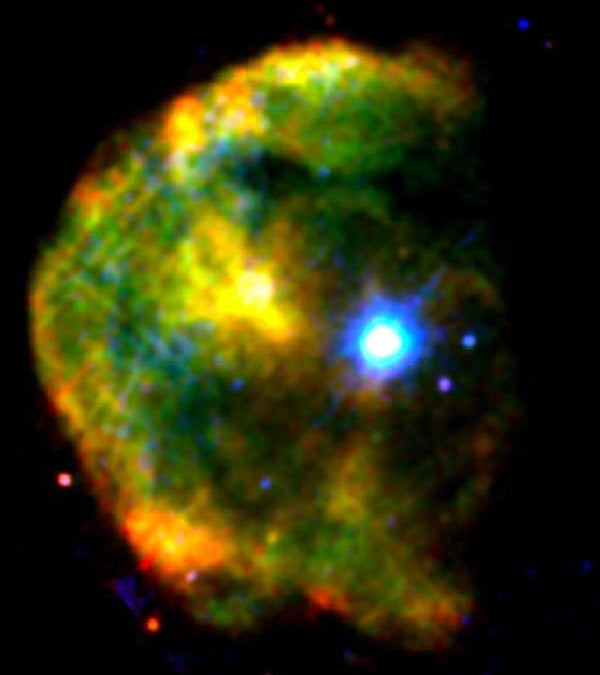

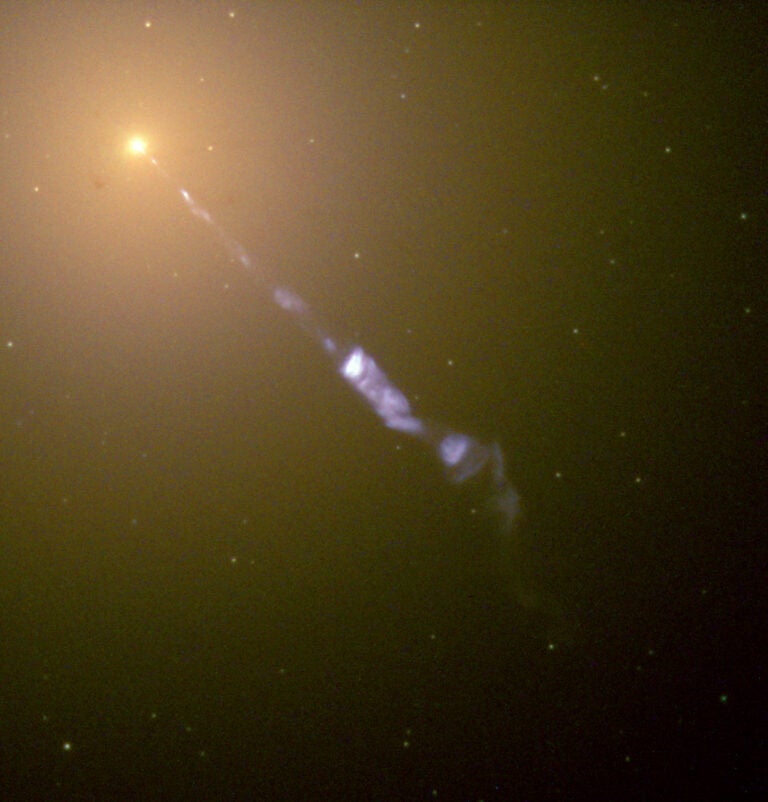

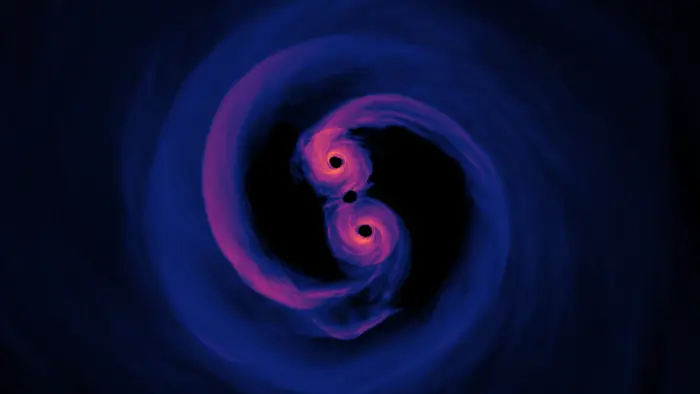

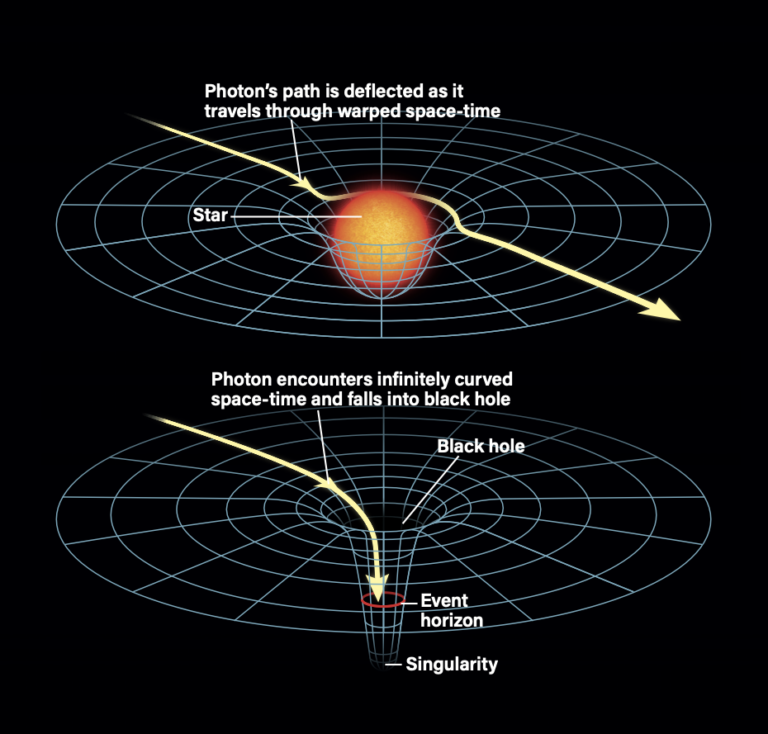

They have ruled out terrestrial sources. The bursts’ energies indicate that they originate from an extreme astrophysical event involving relativistic objects such as neutron stars or black holes.

Study lead Dan Thornton, a Ph.D. student at England’s University of Manchester, said the bursts resulted from extreme events involving large amounts of mass or energy. “A single burst of radio emission of unknown origin was detected outside our galaxy about six years ago, but no one was certain what it was or even if it was real,” he said, “so we have spent the last four years searching for more of these explosive, short-duration radio bursts. [Our] paper describes four more bursts, removing any doubt that they are real. The radio bursts last for just a few milliseconds, and the furthest one that we detected was 11 billion light-years away.”

Astonishingly, the findings — taken from a tiny fraction of the sky — also suggest that one of these signals should go off every 10 seconds. “The bursts last only a tenth of the blink of an eye,” said Michael Kramer, the director of the Max Planck Institute in Bonn, Germany. “With current telescopes, we need to be lucky to look at the right spot at the right time. But if we could view the sky with ‘radio eyes,’ there would be flashes going off all over the sky every day.”

The team, which included researchers from the United Kingdom, Germany, Italy, Australia, and the U.S., used the Parkes 64-meter radio telescope in Australia to obtain their results. Co-author Matthew Bailes of the Swinburne University of Technology in Melbourne thinks the origin of these explosive bursts may be from magnetic neutron stars, known as “magnetars.” “Magnetars can give off more energy in a millisecond than our Sun does in 300,000 years and are a leading candidate for the burst,” he said.

The researchers say their results also will provide a way of finding out the properties of space between Earth and where the bursts occurred. “We are still not sure about what makes up the space between galaxies,” said co-author Ben Stappers of Manchester’s School of Physics and Astronomy, “so we will be able to use these radio bursts like probes in order to understand more about some of the missing matter in the universe. We are now starting to … look for these bursts in real time.”