Recent images from NASA’s MESSENGER spacecraft provided new insights showing that at least the younger plains resulted from vigorous volcanic activity. Yet scientists were unable to establish limits on how far into the past this volcanic activity may have occurred or how much of the planet’s surface may have been resurfaced by old volcanic plains.

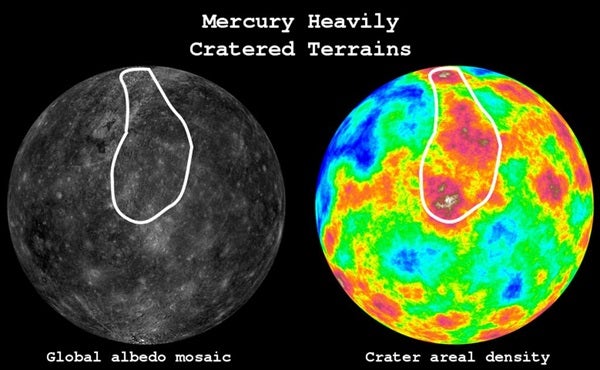

Now, a team of scientists has concluded that the oldest visible terrains on Mercury have an age of 4 billion to 4.1 billion years, and that the first 400 to 500 million years of the planet’s evolution are not recorded on its surface. To reach its conclusion, the team measured the sizes and numbers of craters on the most heavily cratered terrains using images obtained by the MESSENGER spacecraft during its first year in orbit around Mercury. Team members then extrapolated to Mercury a model that was originally developed for comparing the Moon’s crater distribution to a chronology based on the ages of rock samples gathered during the Apollo missions.

“By comparing the measured craters to the number and spatial distribution of large impact basins on Mercury, we found that they started to accumulate at about the same time, suggesting that the resetting of Mercury’s surface was global and likely due to volcanism,” said Marchi.

Those results set the age boundary for the oldest terrains on Mercury to be contemporary with the so-called Late Heavy Bombardment (LHB), a period of intense asteroid and comet impacts recorded in lunar and asteroidal rocks and by the numerous craters on the Moon, Earth, and Mars, as well as Mercury.

“Meanwhile, the age of the youngest and broadest volcanic provinces visible on Mercury was determined to be about 3.6 billion to 3.8 billion years ago, just after the end of the Late Heavy Bombardment,” Marchi said.

Altogether, the results indicate that the time agreement between the onset of the LHB and the global resurfacing of Mercury implies not only that the resurfacing was due to volcanism, but also, according to Chapman, that “the impact of large projectiles hitting Mercury’s thin solid crust during the LHB may have enhanced the observed global resurfacing.”