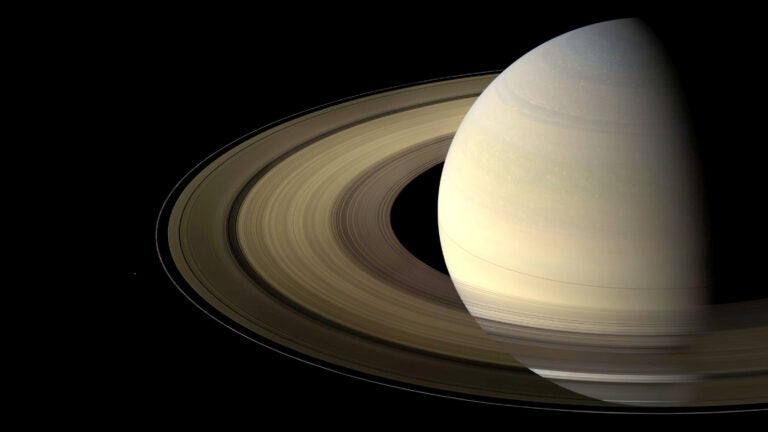

Trojans are asteroids that share a planet’s orbit, occupying stable positions known as Lagrangian points. Astronomers considered Trojans’ presence at Uranus unlikely because they thought the gravitational pull of larger neighboring planets would destabilize and expel any uranian Trojans over the age of the solar system.

To determine how the 37-mile-wide (60 kilometers) ball of rock and ice ended up sharing an orbit with Uranus, the astronomers created a simulation of the solar system and its co-orbital objects, including Trojans.

“Surprisingly, our model predicts that at any given time 3 percent of scattered objects between Jupiter and Neptune should be co-orbitals of Uranus or Neptune,” said Mike Alexandersen from UBC. No one had ever computed this percentage and is much higher than previous estimates.

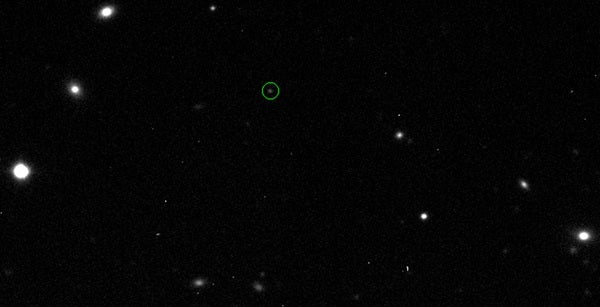

Scientists have discovered several temporary Trojans and co-orbitals in the solar system during the past decade. QF99 is one of those temporary objects. And it was only recently — within the last few hundred thousand years — ensnared by Uranus and set to escape the planet’s gravitational pull in about a million years.

“This tells us something about the current evolution of the solar system,” said Alexandersen. “By studying the process by which Trojans become temporarily captured, one can better understand how objects migrate into the planetary region of the solar system.”