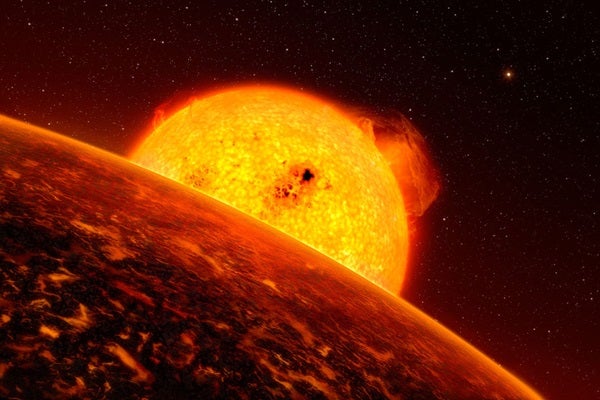

Most gas giant exoplanets with orbital periods less than or equal to a few days are unstable. This is due to decay in their orbits caused by the effects of their star’s proximity. For rocky or icy planets, this disruption could bring them close enough to the star that the force of their own gravity can no longer hold them together in the face of the star’s gravity.

Motivated by these considerations, Brian Jackson of the Carnegie Institution for Science’s Department of Terrestrial Magnetism and his team conducted a search for short-period transiting objects in the publicly available Kepler data set. Their preliminary survey revealed about a half-dozen planetary candidates, all with periods less than 12 hours. Even with masses of only a few times that of Earth, the short periods mean they might be detectable by currently operating ground-based facilities.

If confirmed, these planets would be among the shortest-period planets ever discovered, and if common, such planets would be particularly amenable to discovery by the planned TESS mission, which will look for, among other things, short-period rocky planets.