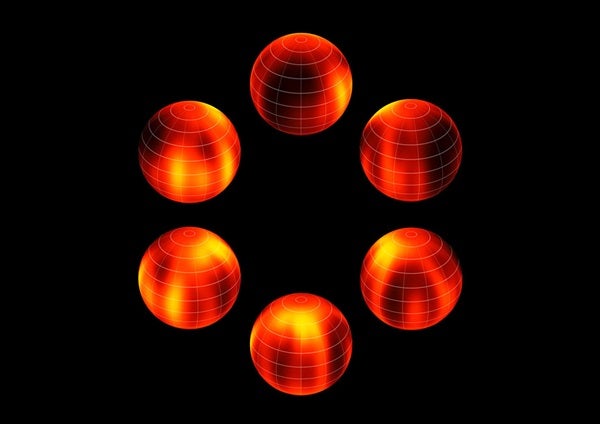

The figure shows the object at six equally spaced times as it rotates once on its axis.

Brown dwarfs fill the gap between gas giant planets, such as Jupiter and Saturn, and faint cool stars. They do not contain enough mass to initiate nuclear fusion in their cores and can only glow feebly at infrared wavelengths of light. The first confirmed brown dwarf was only found 20 years ago, and only a few hundred of these elusive objects are known.

The closest brown dwarfs to the solar system form a pair called Luhman 16AB that lie just 6 light-years from Earth in the southern constellation Vela the Sail. This pair is the third-closest system to Earth, after Alpha Centauri and Barnard’s Star, but it was only discovered in early 2013. The fainter component, Luhman 16B, had already been found to be changing slightly in brightness every few hours as it rotated — a clue that it might have marked surface features.

Now astronomers have used the power of ESO’s VLT not just to image these brown dwarfs, but to map out dark and light features on the surface of Luhman 16B.

“Previous observations suggested that brown dwarfs might have mottled surfaces, but now we can actually map them,” said Ian Crossfield from the Max Planck Institute for Astronomy in Heidelberg, Germany. “Soon, we will be able to watch cloud patterns form, evolve, and dissipate on this brown dwarf — eventually, exometeorologists may be able to predict whether a visitor to Luhman 16B could expect clear or cloudy skies.”

To map the surface, the astronomers used a clever technique. They observed the brown dwarfs using the CRIRES instrument on the VLT. This allowed them not only to see the changing brightness as Luhman 16B rotated, but also to see whether dark and light features were moving away from or toward the observer. By combining all this information, they could re-create a map of the dark and light patches of the surface.

The atmospheres of brown dwarfs are very similar to those of hot gas giant exoplanets, so by studying comparatively easy-to-observe brown dwarfs astronomers also can learn more about the atmospheres of young giant planets — many of which will be found in the near future with the new SPHERE instrument that will be installed on the VLT in 2014.

“Our brown dwarf map helps bring us one step closer to the goal of understanding weather patterns in other solar systems,” said Crossfield. “From an early age, I was brought up to appreciate the beauty and utility of maps. It’s exciting that we’re starting to map objects out beyond the solar system!”

Note that the faint fine detail on the surface of Luhman 16B has been added for artistic effect. // Credit: ESO/I. Crossfield/N. Risinger