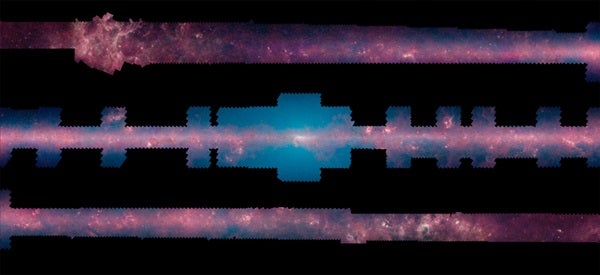

The star-studded panorama of our galaxy is constructed from more than 2 million infrared snapshots taken over the past 10 years by NASA’s Spitzer Space Telescope.

“If we actually printed this out, we’d need a billboard as big as the Rose Bowl Stadium to display it,” said Robert Hurt from NASA’s Spitzer Space Science Center in Pasadena, California. “Instead, we’ve created a digital viewer that anyone, even astronomers, can use.”

The 20-gigapixel mosaic uses Microsoft’s WorldWide Telescope visualization platform. It captures about 3 percent of our sky, but because it focuses on a band around Earth where the plane of the Milky Way lies, it shows more than half of all the galaxy’s stars.

The image, derived primarily from the galactic Legacy Mid-Plane Survey Extraordinaire project (GLIMPSE360) is online at http://www.spitzer.caltech.edu/glimpse360.

Spitzer, launched into space in 2003, has spent more than 10 years studying everything from asteroids in our solar system to the most remote galaxies at the edge of the observable universe. In this time, it has spent a total of 4,142 hours (172 days) taking pictures of the disk, or plane, of our Milky Way Galaxy in infrared light. This is the first time those images have been stitched together into a single expansive view.

Our galaxy is a flat spiral disk; our solar system sits in the outer one-third of the Milky Way, in one of its spiral arms. When we look toward the center of our galaxy, we see a crowded, dusty region jam-packed with stars. Visible-light telescopes cannot look as far into this region because the amount of dust increases with distance, blocking visible starlight. Infrared light, however, travels through the dust and allows Spitzer to view past the galaxy’s center.

“Spitzer is helping us determine where the edge of the galaxy lies,” said Ed Churchwell from the University of Wisconsin-Madison. “We are mapping the placement of the spiral arms and tracing the shape of the galaxy.”

Using GLIMPSE data, astronomers have created the most accurate map of the large central bar of stars that marks the center of the galaxy, revealing the bar to be slightly larger than previously thought. GLIMPSE images have also shown a galaxy riddled with bubbles. These bubble structures are cavities around massive stars, which blast wind and radiation into their surroundings.

All together, the data allow scientists to build a more global model of stars and star formation in the galaxy — what some call the “pulse” of the Milky Way. Spitzer can see faint stars in the “backcountry” of our galaxy — the outer darker regions that went largely unexplored before.

“There are a whole lot more lower-mass stars seen now with Spitzer on a large scale, allowing for a grand study,” said Barbara Whitney from the University of Wisconsin-Madison. “Spitzer is sensitive enough to pick these up and light up the entire ‘countryside’ with star formation.”

The Spitzer team previously released an image compilation showing 130° of our galaxy, focused on its hub. The new 360° view will guide NASA’s upcoming James Webb Space Telescope to the most interesting sites of star formation, where it will make even more detailed infrared observations.

Some sections of the GLIMPSE mosaic include longer-wavelength data from NASA’s Wide-field Infrared Survey Explorer (WISE), which scanned the whole sky in infrared light.

The GLIMPSE data are also part of a citizen science project, where users can help catalog bubbles and other objects in our Milky Way galaxy.