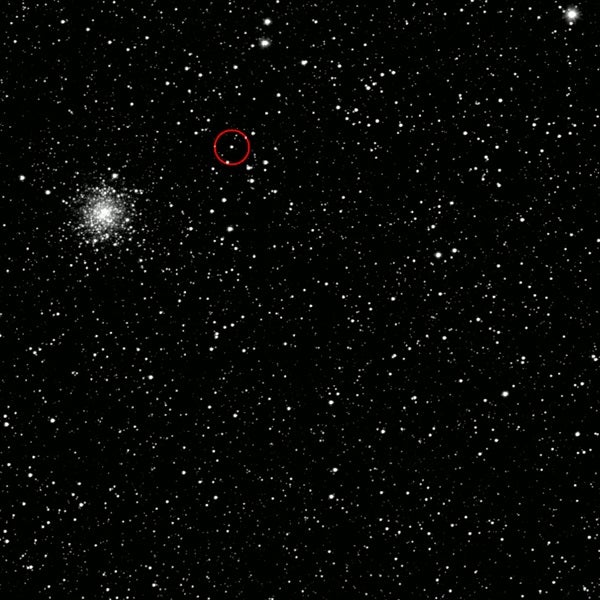

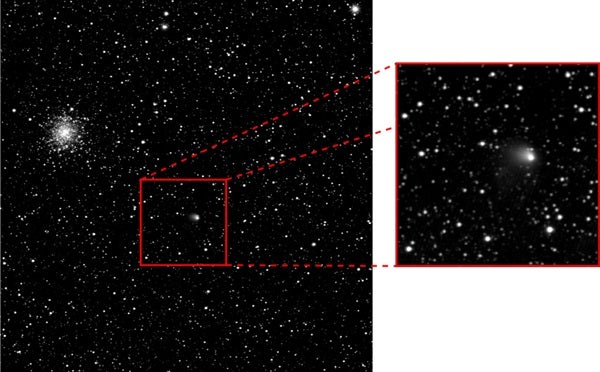

The sequence of images presented here of comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko were taken between March 27 and May 4 as the gap between craft and comet closed from around 3 million to 1.3 million miles (5 million to 2 million kilometers).

By the end of the sequence, the comet’s dusty veil, the “coma,” extends some 800 miles (1,300km) into space. By comparison, the nucleus is roughly only 2.5 miles (4km) across and cannot yet be “resolved.”

The coma has developed as a result of the comet moving progressively closer to the Sun along its 6.5-year orbit. Although it is still more than 400 million miles (600 million km) from the Sun — more than four times the distance between Earth and the Sun — its surface has already started to warm, causing its surface ices to sublimate and gas to escape from its rock-ice nucleus. As the gas escapes, it also carries a cloud of tiny dust particles out into space, which slowly expands to create the coma.

As the comet continues to move closer to the Sun, the warming continues and activity rises, and pressure from the solar wind will eventually cause some of the material to stream out into a long tail.

Rosetta and the comet will be closest to the Sun in August 2015, between the orbits of Earth and Mars.

The onset of activity now offers scientists the opportunity to study dust production and structures within the coma before getting much closer.

In addition, tracking the periodic changes in brightness reveals that the nucleus is rotating every 12.4 hours, about 20 minutes shorter than previously thought.

“These early observations are helping us to develop models of the comet that will be essential to help us navigate around it once we get closer,” said Sylvain Lodiot from ESA.

OSIRIS and the spacecraft’s dedicated navigation cameras have been regularly acquiring images to help determine Rosetta’s exact trajectory relative to the comet. Using this information, the spacecraft has already started a series of maneuvers that will slowly bring it in line with the comet before making its rendezvous in the first week of August.

Detailed scientific observations will then help find the best location on the comet for the Philae lander’s descent to the surface in November.

The images shown here were taken during a six-week period that saw the orbiter’s 11 science experiments and the lander and its 10 instruments switched back on and checked out after more than 2.5 years of hibernation.

Earlier this week, a formal review brought these commissioning activities to a close, giving the official “go” for routine science operations.

“We have a challenging three months ahead of us as we navigate closer to the comet, but after a 10-year journey, it’s great to be able to say that our spacecraft is ready to conduct unique science at comet 67P/C-G,” said Fred Jansen from ESA.