By mining such archives, a team of astronomers led by Ivana Damjanov of the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics (CfA) in Cambridge, Massachusetts, has found a treasure-trove of “red nugget” galaxies. These galaxies are compact and densely packed with old red stars. Their abundance provides new constraints on theoretical models of galaxy formation and evolution. “These red nugget galaxies were hiding in plain view, masquerading as stars,” said Damjanov.

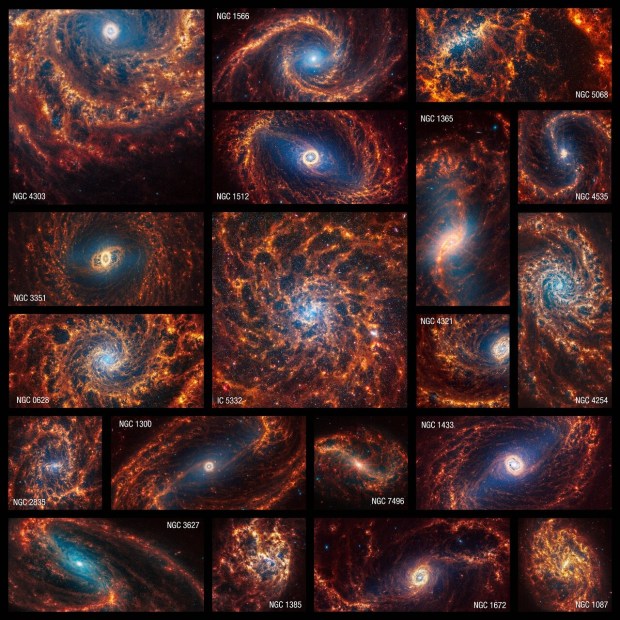

When the universe was young, dense massive galaxies nicknamed “red nuggets” were common. These galaxies are 10 times more massive than the Milky Way, but their stars are packed into a volume a hundred times smaller than our galaxy.

Mysteriously, astronomers searching the older, nearer universe could not find any of these objects. Their apparent disappearance, if real, signaled a surprising turn in galaxy evolution.

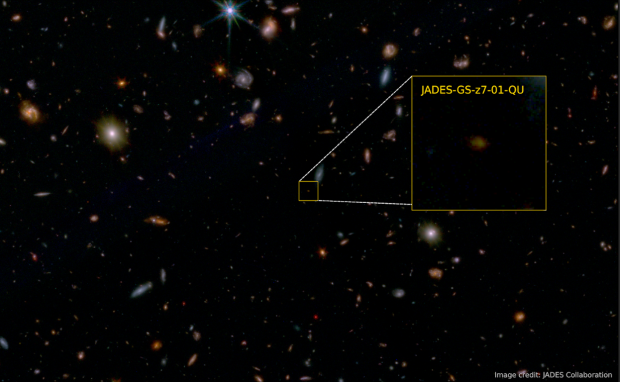

To find nearby examples, Damjanov and her colleagues Margaret Geller, Ho Seong Hwang, and Igor Chilingarian from the Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory combed through the database of the largest survey of the universe, the Sloan Digital Sky Survey. The red nugget galaxies are so small that they appear like stars in Sloan photographs due to blurring from Earth’s atmosphere. However, their spectra give away their true nature.

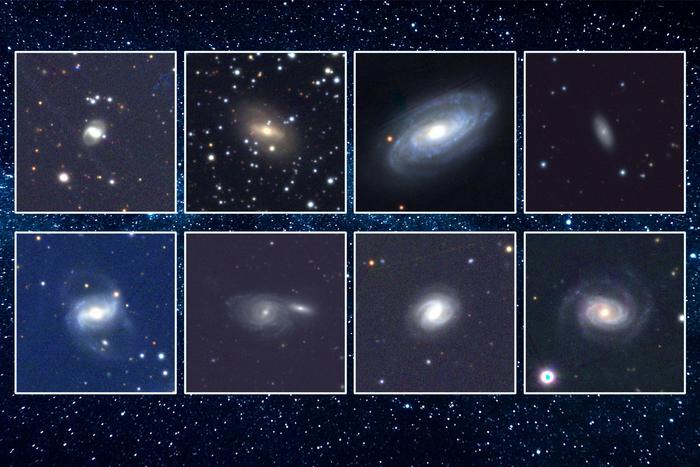

The team identified several hundred red nugget candidates in the Sloan data. Then they searched a variety of online telescope archives in order to confirm their findings. In particular, high-quality images from the Canada-France-Hawaii Telescope and the Hubble Space Telescope showed that about 200 of the candidates were galaxies very similar to their red-nugget cousins in the distant young universe.

“Now we know that many of these amazingly small, dense, but massive galaxies survive. They are a fascinating test of our understanding of the way galaxies form and evolve,” said Geller.

The large number of red nuggets discovered in Sloan told the team how abundant those galaxies were in the middle-aged universe. That number then can be compared to computer models of galaxy formation. Different models for the way galaxies grow predict different abundances.

The picture that matches the observations is one where red nuggets begin their lives as very small objects in the young universe. During the next 10 billion years, some of them collide and merge with other smaller and less massive galaxies. Some red nuggets manage to avoid collisions and remain compact as they age. The result is a variety of elliptical galaxies with different sizes and masses, some very compact and some more extended.

“Many processes work together to shape the rich landscape of galaxies we see in the nearby universe,” said Damjanov.