At the Las Campanas Observatory in Chile, Faherty, along with a team including Carnegie’s Andrew Monson, used the FourStar near infrared camera to detect the coldest brown dwarf ever characterized. Their findings are the result of 151 images taken over three nights and combined. The object, named WISE J085510.83-071442.5 (W0855), was first seen by NASA’s Wide-Field Infrared Explorer mission and published earlier this year, but it was not known if it could be detected by Earth-based facilities.

“This was a battle at the telescope to get the detection,” said Faherty.

“This is a great result,” said Chris Tinney from the Australian Center for Astrobiology. “This object is so faint, and it’s exciting to be the first people to detect it with a telescope on the ground.”

Brown dwarfs aren’t quite small stars, but they aren’t quite giant planets either. They are too small to sustain the hydrogen fusion process that fuels stars. Their temperatures can range from nearly as hot as a star to as cool as a planet, and their masses also range between star-like and giant planet-like. They are of particular interest to scientists because they offer clues to star formation processes. They also overlap with the temperatures of planets, but are much easier to study since they are commonly found in isolation.

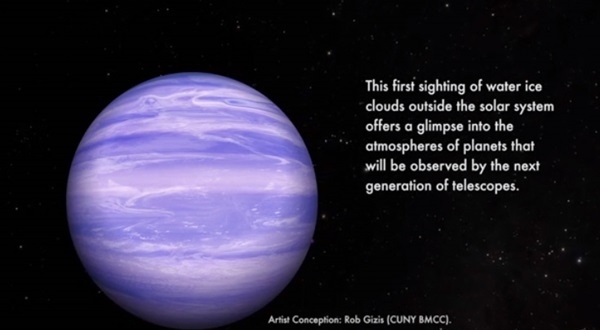

W0855 is the fourth-closest system to our Sun, practically a next-door neighbor in astronomical distances. A comparison of the team’s near-infrared images of W0855 with models for predicting the atmospheric content of brown dwarfs showed evidence of frozen clouds of sulfide and water.

“Ice clouds are predicted to be very important in the atmospheres of planets beyond our solar system, but they’ve never been observed outside of it before now,” Faherty said.