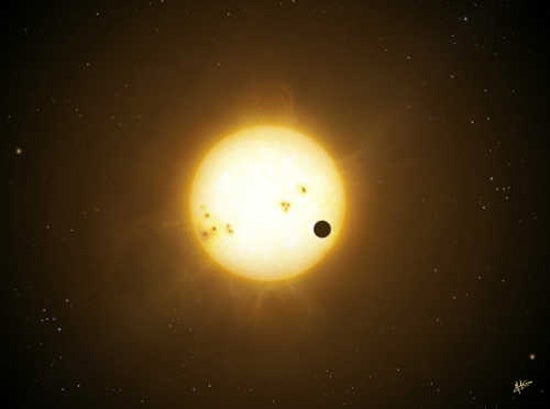

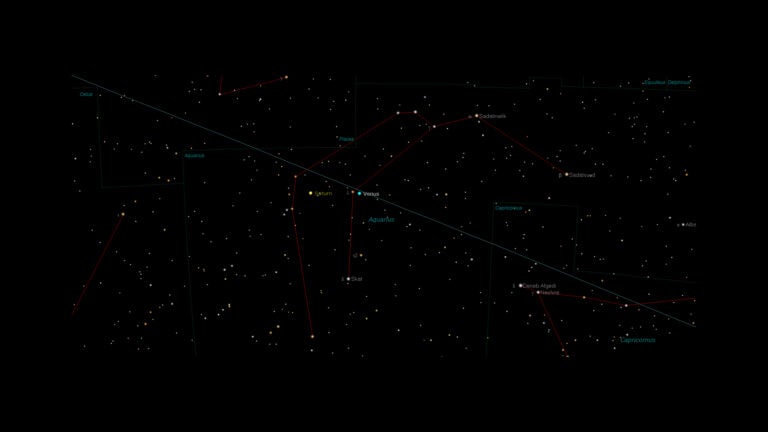

A team of British, Swiss, and Belgian astronomers made the discoveries around the stars WASP-94A and WASP-94B. The British WASP-South survey, operated by Keele University, found tiny dips in the light of WASP-94A, suggesting that a Jupiter-like planet was transiting the star. Swiss astronomers then showed the existence of planets around both WASP-94A and its twin, WASP-94B.

“We observed the other star by accident and then found a planet around that one also!” said Marion Neveu-VanMalle from the Geneva Observatory.

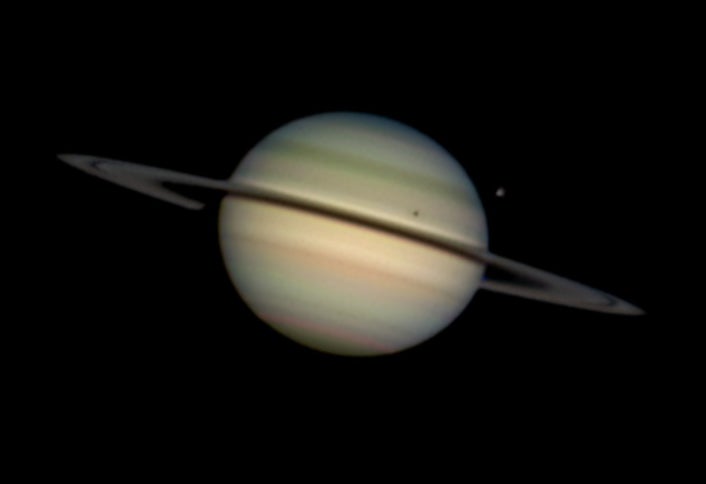

Hot Jupiter planets are much closer to their stars than our own Jupiter, with a “year” lasting only a few days. They are rare, so it would be unlikely to find two hot Jupiters in the same star system by chance. Perhaps WASP-94 has just the right conditions for producing hot Jupiters? If so, WASP-94 could be an important system for understanding why hot Jupiters are so close to the star they orbit.

The existence of huge Jupiter-sized planets so near to their stars is a long-standing puzzle because they cannot form near to the star where it is far too hot. They must form much farther out, where it is cool enough for ices to freeze out of the protoplanetary disk circling the young star, hence forming the core of a new planet. Something must then move the planet into a close orbit, and one likely mechanism is an interaction with another planet or star. Finding hot Jupiter planets in two stars of a binary pair might allow scientists to study the processes that move the planets inward.

“WASP-94 could turn into one of the most important discoveries from WASP-South,” said Coel Hellier of Keele University in the United Kingdom. “The two stars are relatively bright, making it easy to study their planets, so WASP-94 could be used to discover the compositions of the atmospheres of exoplanets.”

The WASP survey is the world’s most successful search for hot Jupiter planets that pass in front of — transit — their star. The WASP-South survey instrument scans the sky every clear night, searching hundreds of thousands of stars for transits. The Belgian team selects the best WASP candidates by obtaining high-quality data of transit light curves. Geneva Observatory astronomers then show that the transiting body is a planet by measuring its mass, which they do by detecting the planet’s gravitational tug on the host star.

The collaboration has now found over 100 hot Jupiter planets, many of them around relatively bright stars that are easy to study, leading to strong interest in WASP planets from astronomers worldwide.