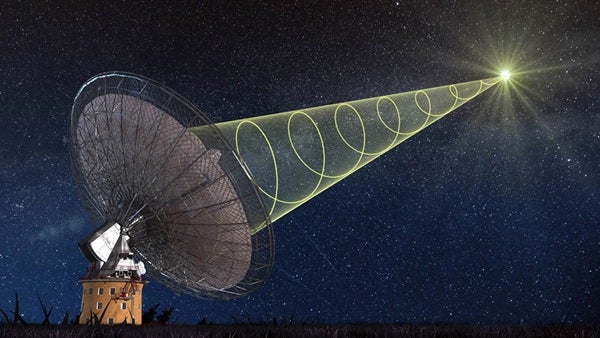

Over the past few years, astronomers have observed a new phenomenon, a brief burst of radio waves, lasting only a few milliseconds. It was first seen by chance in 2007 when astronomers went through archival data from the Parkes Radio Telescope in Eastern Australia. Since then they have seen six more such bursts in the Parkes telescope’s data, and a seventh burst was found in the data from the Arecibo telescope in Puerto Rico. They were almost all discovered long after they had occurred, but then astronomers began to look specifically for them right as they happen.

Radio, X-ray, and visible light

A team of astronomers in Australia developed a technique to search for these “fast radio bursts” so they could look for the bursts in real time. The technique worked, and now a group of astronomers, led by Emily Petroff from Swinburne University of Technology, has succeeded in observing the first “live” burst with the Parkes telescope. The characteristics of the event indicated that the source of the burst was up to 5.5 billion light-years from Earth.

Now that they had the burst location and as soon as it was observed, a number of other telescopes around the world were alerted — both on the ground and in space — in order to make follow-up observations on other wavelengths.

“Using the Swift space telescope, we can observe light in the X-ray region, and we saw two X-ray sources at that position,” said Daniele Malesani from the University of Copenhagen in Denmark.

Then the two X-ray sources were observed using the Nordic Optical Telescope on La Palma. “We observed in visible light, and we could see that there were two quasars, that is to say, active black holes. They had nothing to do with the radio wave bursts, but just happen to be located in the same direction,” said Giorgos Leloudas from the University of Copenhagen and Weizmann Institute, Israel.

Further investigation

So now what? Even though they captured the radio wave burst while it was happening and could immediately make follow-up observations at other wavelengths ranging from infrared light, visible light, ultraviolet light, and X-ray waves, they found nothing. But did they discover anything?

“We found out what it wasn’t. The burst could have hurled out as much energy in a few milliseconds as the Sun does in an entire day. But the fact that we did not see light in other wavelengths eliminates a number of astronomical phenomena that are associated with violent events such as gamma-ray bursts from exploding stars and supernovae, which were otherwise candidates for the burst,” said Malesani.

But the burst left another clue. The Parkes detection system captured the polarization of the light. Polarization is the direction in which electromagnetic waves oscillate and they can be linearly or circularly polarized. The signal from the radio wave burst was more than 20 percent circularly polarized, and it suggests that there is a magnetic field in the vicinity.

“The theories are now that the radio wave burst might be linked to a very compact type of object — such as neutron stars or black holes — and the bursts could be connected to collisions or ‘star quakes.’ Now we know more about what we should be looking for,” said Malesani.