Eric Mamajek from the University of Rochester in New York and his collaborators analyzed the velocity and trajectory of a low-mass star system nicknamed “Scholz’s star.”

The star’s trajectory suggests that 70,000 years ago it passed roughly 52,000 astronomical units away (or about 0.8 light-years, which equals 5 trillion miles [8 trillion kilometers]). This is astronomically close; our closest neighbor star Proxima Centauri is 4.2 light-years distant. In fact, the astronomers explained that they are 98 percent certain that it went through what is known as the “outer Oort Cloud” — a region at the edge of the solar system filled with trillions of comets a mile or more across that are thought to give rise to long-period comets orbiting the Sun after their orbits are perturbed.

The star originally caught Mamajek’s attention during a discussion with Valentin D. Ivanov from the European Southern Observatory. Scholz’s star had an unusual mix of characteristics: Despite being fairly close (“only” 20 light-years away), it showed slow tangential motion, that is, motion across the sky. The radial velocity measurements taken by Ivanov and collaborators, however, showed the star moving almost directly away from the solar system at considerable speed.

“Most stars this nearby show much larger tangential motion,” said Mamajek. “The small tangential motion and proximity initially indicated that the star was most likely either moving towards a future close encounter with the solar system or it had recently come close to the solar system and was moving away. Sure enough, the radial velocity measurements were consistent with it running away from the Sun’s vicinity, and we realized it must have had a close flyby in the past.”

To work out its trajectory, the astronomers needed both pieces of data, the tangential velocity and the radial velocity. Ivanov and collaborators had characterized the recently discovered star through measuring its spectrum and radial velocity via Doppler shift. These measurements were carried out using spectrographs on large telescopes in both South Africa and Chile: the Southern African Large Telescope (SALT) and the Magellan Telescope at Las Campanas Observatory, respectively.

Once the researchers pieced together all the information, they figured out that Scholz’s star was moving away from our solar system and traced it back in time to its position 70,000 years ago, when their models indicated it came closest to our Sun.

Until now, the top candidate for the closest flyby of a star to the solar system was the so-called “rogue star” HIP 85605, which was predicted to come close to our solar system 240,000 to 470,000 years from now. However, Mamajek and his collaborators have also demonstrated that the original distance to HIP 85605 was likely underestimated by a factor of 10. At its more likely distance of about 200 light-years, HIP 85605’s newly calculated trajectory would not bring it within the Oort Cloud.

Mamajek worked with former University of Rochester undergraduate Scott Barenfeld to simulate 10,000 orbits for the star, taking into account the star’s position, distance, and velocity, the Milky Way Galaxy’s gravitational field, and the statistical uncertainties in all of these measurements. Of those 10,000 simulations, 98 percent of the simulations showed the star passing through the outer Oort Cloud, but fortunately only one of the simulations brought the star within the inner Oort Cloud, which could trigger so-called “comet showers.”

While the close flyby of Scholz’s star likely had little impact on the Oort Cloud, Mamajek points out that “other dynamically important Oort Cloud perturbers may be lurking among nearby stars.” The recently launched European Space Agency Gaia satellite is expected to map out the distances and measure the velocities of a billion stars. With the Gaia data, astronomers will be able to tell which other stars may have had a close encounter with us in the past or will in the distant future.

Currently, Scholz’s star is a small dim red dwarf in the constellation Monoceros, about 20 light-years away. However, at the closest point in its flyby of the solar system, Scholz’s star would have been a 10th-magnitude star — about 50 times fainter than can normally be seen with the naked eye at night. It is magnetically active, however, which can cause stars to “flare” and briefly become thousands of times brighter. So it is possible that Scholz’s star may have been visible to the naked eye by our ancestors 70,000 years ago for minutes or hours at a time during rare flaring events.

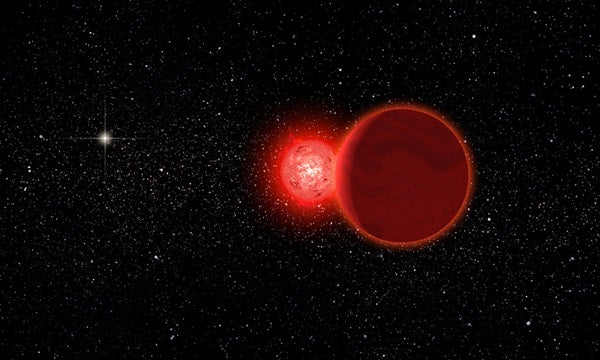

The star is part of a binary star system: a low-mass red dwarf star with mass about 8 percent that of the Sun and a “brown dwarf” companion with mass about 6 percent that of the Sun. Brown dwarfs are considered “failed stars”; their masses are too low to fuse hydrogen in their cores like a star, but they are still much more massive than gas giant planets like Jupiter.

The formal designation of the star is “WISE J072003.20-084651.2,” but it has been nicknamed “Scholz’s star” to honor its discoverer — astronomer Ralf-Dieter Scholz of the Leibniz-Institut für Astrophysik Potsdam (AIP) in Germany, who first reported the discovery of the dim nearby star in late 2013. The “WISE” part of the designation refers to NASA’s Wide-field Infrared Survey Explorer (WISE) mission, which mapped the entire sky in infrared light in 2010 and 2011, and the “J-number” part of the designation refers to the star’s celestial coordinates.