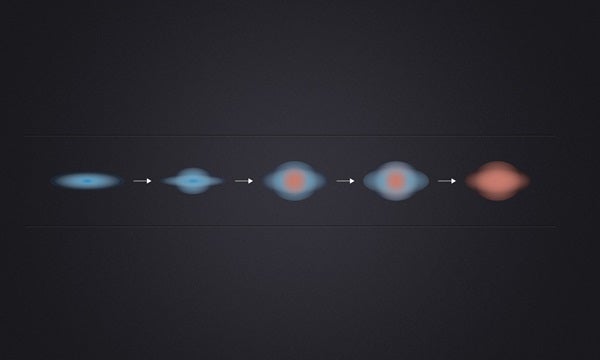

This diagram illustrates this process. Galaxies in the early universe appear at the left. The blue regions are where star formation is in progress and the red regions are the “dead” regions where only older redder stars remain, and there are no more young blue stars being formed. The resulting giant spheroidal galaxies in the modern universe appear on the right.

A major astrophysical mystery has centered on how massive, quiescent elliptical galaxies, common in the modern universe, quenched their once furious rates of star formation. Such colossal galaxies, often also called spheroids because of their shape, typically pack in stars 10 times as densely in the central regions as in our home galaxy, the Milky Way, and have about 10 times its mass.

Astronomers refer to these big galaxies as red and dead as they exhibit an ample abundance of ancient red stars but lack young blue stars and show no evidence of new star formation. The estimated ages of the red stars suggest that their host galaxies ceased to make new stars about 10 billion years ago. This shutdown began right at the peak of star formation in the universe, when many galaxies were still giving birth to stars at a pace about 20 times faster than nowadays.

“Massive dead spheroids contain about half of all the stars that the universe has produced during its entire life,” said Sandro Tacchella of ETH Zurich in Switzerland. “We cannot claim to understand how the universe evolved and became as we see it today unless we understand how these galaxies come to be.”

Tacchella and colleagues observed a total of 22 galaxies, spanning a range of masses, from an era about 3 billion years after the Big Bang. The SINFONI instrument on ESO’s VLT collected light from this sample of galaxies, showing precisely where they were churning out new stars. SINFONI could make these detailed measurements of distant galaxies thanks to its adaptive optics system, which largely cancels out the blurring effects of Earth’s atmosphere.

The researchers also trained the NASA/ESA Hubble Space Telescope on the same set of galaxies, taking advantage of the telescope’s location in space above our planet’s distorting atmosphere. Hubble’s WFC3 camera snapped images in the near-infrared, revealing the spatial distribution of older stars within the actively star-forming galaxies.

“What is amazing is that SINFONI’s adaptive optics system can largely beat down atmospheric effects and gather information on where the new stars are being born, and do so with precisely the same accuracy as Hubble allows for the stellar mass distributions,” said Marcella Carollo from ETH Zurich.

According to the new data, the most massive galaxies in the sample kept up a steady production of new stars in their peripheries. In their bulging, densely packed centers, however, star formation had already stopped.

“The newly demonstrated inside-out nature of star formation shutdown in massive galaxies should shed light on the underlying mechanisms involved, which astronomers have long debated,” said Alvio Renzini, Padova Observatory of the Italian National Institute of Astrophysics.

A leading theory is that star-making materials are scattered by torrents of energy released by a galaxy’s central supermassive black hole as it sloppily devours matter. Another idea is that fresh gas stops flowing into a galaxy, starving it of fuel for new stars and transforming it into a red and dead spheroid.

“There are many different theoretical suggestions for the physical mechanisms that led to the death of the massive spheroids,” said Natascha Förster Schreiber of the Max-Planck-Institut für Extraterrestrische Physik in Garching, Germany. “Discovering that the quenching of star formation started from the centers and marched its way outwards is a very important step towards understanding how the universe came to look like it does now.”