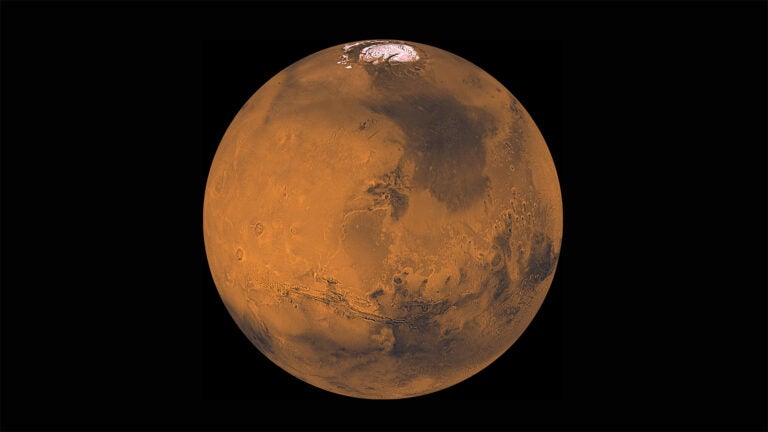

Perchlorate identified in martian soil by the Curiosity mission, and previously by NASA’s Phoenix Mars Lander mission, has properties of absorbing water vapor from the atmosphere and lowering the freezing temperature of water. This has been proposed for years as a mechanism for possible existence of transient liquid brines at higher latitudes on modern Mars, despite the Red Planet’s cold and dry conditions.

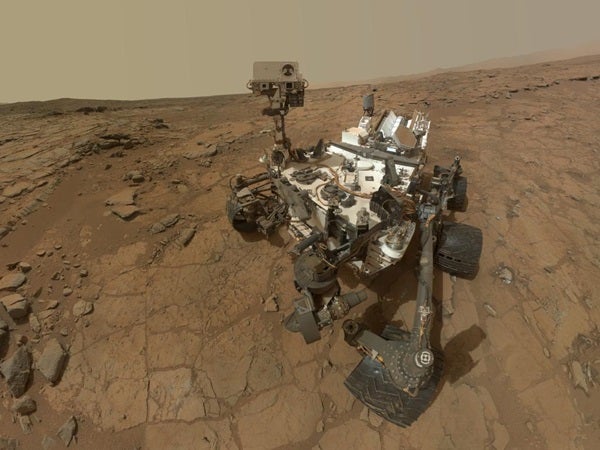

New calculations were based on more than a full Mars year of temperature and humidity measurements by Curiosity. They indicate that conditions at the rover’s near-equatorial location were favorable for small quantities of brine to form during some nights throughout the year, drying out again after sunrise. Conditions should be even more favorable at higher latitudes where colder temperatures and more water vapor can result in higher relative humidity more often.

“Liquid water is a requirement for life as we know it and a target for Mars exploration missions,” said the report’s lead author, Javier Martin-Torres of the Spanish Research Council in Spain and Lulea University of Technology in Sweden, a member of Curiosity’s science team. “Conditions near the surface of present-day Mars are hardly favorable for microbial life as we know it, but the possibility for liquid brines on Mars has wider implications for habitability and geological water-related processes.”

The weather data in the report come from the Curiosity’s Rover Environmental Monitoring Station (REMS), which was provided by Spain and includes a relative-humidity sensor and a ground-temperature sensor. NASA’s Mars Science Laboratory Project is using Curiosity to investigate both ancient and modern environmental conditions in Mars’ Gale Crater region. The report also draws on measurements of hydrogen in the ground by the rover’s Dynamic Albedo of Neutrons (DAN) instrument, from Russia.

“We have not detected brines, but calculating the possibility that they might exist in Gale Crater during some nights testifies to the value of the round-the-clock and year-round measurements REMS is providing,” said Ashwin Vasavada of NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California.

Curiosity is the first mission to measure relative humidity in the martian atmosphere close to the surface and ground temperature through all times of day and all seasons of the martian year. Relative humidity depends on the temperature of the air, as well as the amount of water vapor in it. Curiosity’s measurements of relative humidity range from about 5 percent on summer afternoons to 100 percent on autumn and winter nights.

Air filling pores in the soil interacts with air just above the ground. When its relative humidity gets above a threshold level, salts can absorb enough water molecules to become dissolved in liquid, a process called deliquescence. Perchlorate salts are especially good at this. Since perchlorate has been identified both at near-polar and near-equatorial sites, it may be present in soils all over the planet.

Researchers using the High Resolution Imaging Science Experiment (HiRISE) camera on NASA’s Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter have in recent years documented numerous sites on Mars where dark flows appear and extend on slopes during warm seasons. These features are called recurring slope lineae (RSL). A leading hypothesis for how they occur involves brines formed by deliquescence.

“Gale Crater is one of the least likely places on Mars to have conditions for brines to form, compared to sites at higher latitudes or with more shading. So if brines can exist there, that strengthens the case they could form and persist even longer at many other locations, perhaps enough to explain RSL activity,” said Alfred McEwen of the University of Arizona in Tucson.