Key Takeaways:

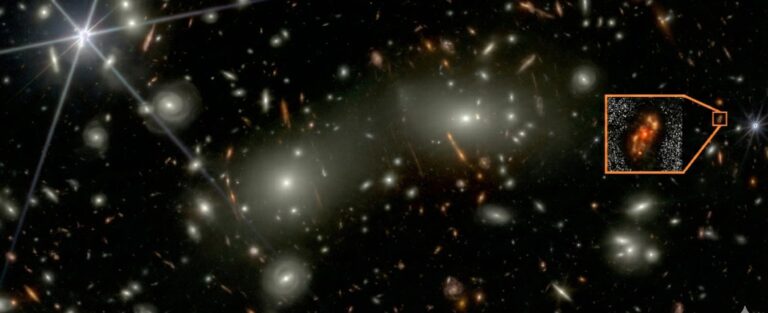

“We are looking at a very intense phase of galaxy evolution,” said Chao-Wei Tsai of NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in Pasadena, California. “This dazzling light may be from the main growth spurt of the galaxy’s black hole.”

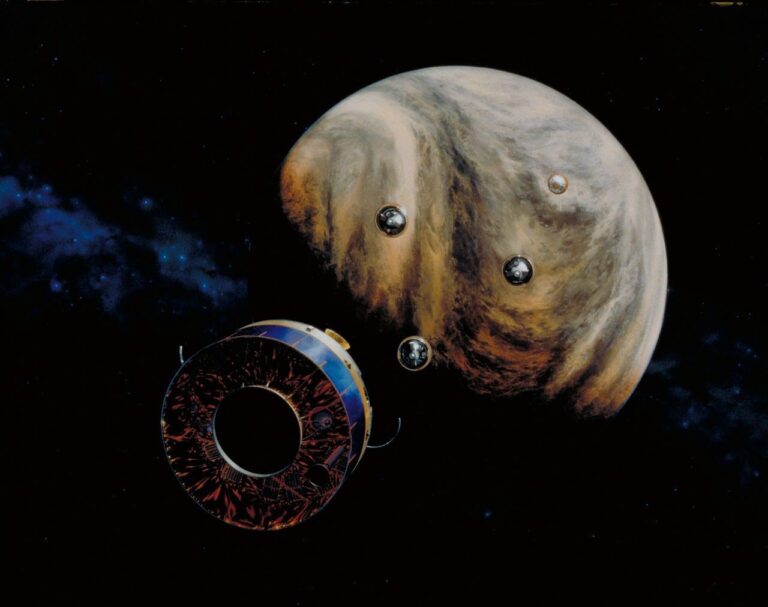

The brilliant galaxy, known as WISE J224607.57-052635.0, may have a behemoth black hole at its belly, gorging itself on gas. Supermassive black holes draw gas and matter into a disk around them, heating the disk to roaring temperatures of millions of degrees and blasting out high-energy, visible, ultraviolet, and X-ray light. The light is blocked by surrounding cocoons of dust. As the dust heats up, it radiates infrared light.

Immense black holes are common at the cores of galaxies, but finding one this big so “far back” in the cosmos is rare. Because light from the galaxy hosting the black hole has traveled 12.5 billion years to reach us, astronomers are seeing the object as it was in the distant past. The black hole was already billions of times the mass of our Sun when our universe was only a tenth of its present age of 13.8 billion years.

The new study outlines three reasons why the black holes in the ELIRGs could have grown so massive. First, they may have been born big. In other words, the “seeds,” or embryonic black holes, might be bigger than thought possible.

“How do you get an elephant?” asked Peter Eisenhardt from JPL. “One way is start with a baby elephant.”

The other two explanations involve either breaking or bending the theoretical limit of black hole feeding called the Eddington limit. When a black hole feeds, gas falls in and heats up, blasting out light. The pressure of the light actually pushes the gas away, creating a limit to how fast the black hole can continuously scarf down matter. If a black hole broke this limit, it could theoretically balloon in size at a breakneck pace. Black holes have previously been observed breaking this limit; however, the black hole in the study would have had to repeatedly break the limit to grow this large.

Alternatively, the black holes might just be bending this limit.

“Another way for a black hole to grow this big is for it to have gone on a sustained binge, consuming food faster than typically thought possible,” said Tsai. “This can happen if the black hole isn’t spinning that fast.”

If a black hole spins slowly enough, it won’t repel its meal as much. In the end, a slow-spinning black hole can gobble up more matter than a fast spinner.

“The massive black holes in ELIRGs could be gorging themselves on more matter for a longer period of time,” said Andrew Blain of the University of Leicester in the United Kingdom. “It’s like winning a hot-dog-eating contest lasting hundreds of millions of years.”

More research is needed to solve this puzzle of these dazzlingly luminous galaxies. The team has plans to better determine the masses of the central black holes. Knowing these objects’ true hefts will help reveal their history, as well as that of other galaxies, in this very crucial and frenzied chapter of our cosmos.

WISE has been finding more of these oddball galaxies in infrared images of the entire sky captured in 2010. By viewing the whole sky with more sensitivity than ever before, WISE has been able to catch rare cosmic specimens that might have been missed otherwise.

The new study reports a total of 20 new ELIRGs, including the most luminous galaxy found to date. These galaxies were not found earlier because of their distance, and because dust converts their powerful visible light into an incredible outpouring of infrared light.

“We found in a related study with WISE that as many as half of the most luminous galaxies only show up well in infrared light,” said Tsai.