X-rays and gamma rays point to some of the most extreme phenomena in the universe, such as stellar explosions, powerful outbursts, and black holes feasting on their surroundings.

In contrast to the peaceful view of the night sky we see with our eyes, the high-energy sky is a dynamic light show, from flickering sources that change their brightness dramatically in a few minutes to others that vary on time scales spanning years or even decades.

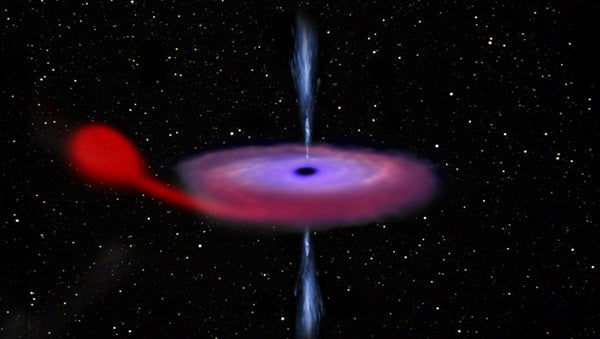

On June 15, 2015, a longtime acquaintance of X-ray and gamma-ray astronomers made its comeback to the cosmic stage — V404 Cygni, a system comprising a black hole and a star orbiting one another. It is located in our Milky Way Galaxy, almost 8,000 light-years away in the constellation Cygnus the Swan.

In this type of binary system, material flows from the star toward the black hole and gathers in a disk, where it is heated up and shines brightly at optical, ultraviolet, and X-ray wavelengths before spiraling into the black hole.

First signs of renewed activity in V404 Cygni were spotted by the Burst Alert Telescope on NASA’s Swift satellite, detecting a sudden burst of gamma rays and then triggering observations with its X-ray telescope. Soon after, Monitor of All-sky X-ray Image (MAXI), part of the Japanese Experiment Module on the International Space Station, observed an X-ray flare from the same patch of the sky.

These first detections triggered a massive campaign of observations from ground-based telescopes and from space-based observatories to monitor V404 Cygni at many different wavelengths across the electromagnetic spectrum. As part of this worldwide effort, ESA’s Integral gamma-ray observatory started monitoring the outbursting black hole on June 17.

“The behavior of this source is extraordinary at the moment, with repeated bright flashes of light on time scales shorter than an hour, something rarely seen in other black hole systems,” said Erik Kuulkers from ESA.

“In these moments, it becomes the brightest object in the X-ray sky — up to 50 times brighter than the Crab Nebula, normally one of the brightest sources in the high-energy sky.”

The V404 Cygni black hole system has not been this bright and active since 1989 when it was observed with the Japanese X-ray satellite Ginga and high-energy instruments onboard the Mir space station.

“The community couldn’t be more thrilled. Many of us weren’t yet professional astronomers back then, and the instruments and facilities available at the time can’t compare with the fleet of space telescopes and the vast network of ground-based observatories we can use today. It is definitely a ‘once-in-a-professional-lifetime’ opportunity,” said Kuulkers.

The 1989 outburst of V404 Cygni was crucial in the study of black holes. Until then, astronomers knew only a handful of objects that they thought could be black holes, and V404 Cygni was one of the most convincing candidates.

A couple of years after the 1989 outburst, once the source had returned to a quieter state, the astronomers were able to see its companion star, which had been outshone by the extreme activity. The star is about half as massive as the Sun, and by studying the relative motion of the two objects in the binary system, it was determined that the companion must be a black hole about 12 times more massive than the Sun.

At the time, the astronomers also looked back at archival data from optical telescopes over the 20th century, finding two previous outbursts, one in 1938 and another one in 1956.

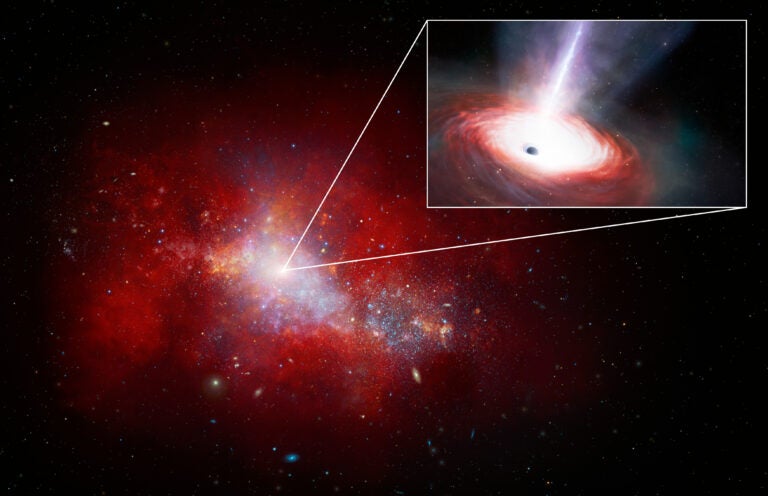

These peaks of activity, which occur every two to three decades, are likely caused by material slowly piling up in the disk surrounding the black hole until eventually reaching a tipping point that dramatically changes the black hole’s feeding routine for a short period.

“Now that this extreme object has woken up again, we are all eager to learn more about the engine that powers the outburst we are observing,” said Carlo Ferrigno from the Integral Science Data Center at the University of Geneva, Switzerland.

“As coordinators of Integral operations, Enrico Bozzo and I received a text message at 1:30 a.m. on June 18 from our burst alert system, which is designed to detect gamma-ray bursts in the Integral data. In this case, it turned out to be ‘only’ an exceptional flare since Integral was observing this incredible black hole — definitely a good reason to be woken up in the middle of the night!”

Since the first outburst detection on June 15 by the Swift satellite, V404 Cygni has remained active, keeping astronomers extremely busy. Over the past week, several teams around the world published over 20 Astronomical Telegrams and other official communications, sharing the progress of the observations at different wavelengths.

This exciting outburst also has been discussed by astronomers attending the European Week of Astronomy and Space Science conference in Tenerife, sharing information on observations that have been made in the past few days.

Integral, too, has been observing this object continuously since June 17, except for some short periods when it was not possible for operational reasons. The X-ray data show huge variability, with intense flares lasting only a couple of minutes, as well as longer outbursts over time scales of a few hours. Integral also recorded a huge emission of gamma rays from this frenzied black hole.

Because different components of a black hole binary system emit radiation at different wavelengths across the spectrum, astronomers are combining high-energy observations with those made at optical and radio wavelengths in order to get a complete view of what is happening in this unique object.

“We have been observing V404 Cygni with the Gran Telescopio Canarias, which has the largest mirror currently available for optical astronomy,” said Teo Muñoz-Darias from the Institute of Astrophysics of the Canaries in Tenerife, Spain.

Using this 10.4-meter telescope located on La Palma, the astronomers can quickly obtain high-quality spectra, thus probing what happens around the black hole on short time scales.

“There are many features in our spectra showing signs of massive outflows of material in the black hole’s environment. We are looking forward to testing our current understanding of black holes and their feeding habits with these rich data,” said Muñoz-Darias.

Radio astronomers all over the world are also joining in this extraordinary observing campaign. The first detection at these long wavelengths was made shortly after the first Swift alert on June 15 with the Arcminute Microkelvin Imager from the Mullard Radio Astronomy Observatory near Cambridge in the United Kingdom, thanks to the robotic mode of this telescope.

Like the data at other wavelengths, these radio observations exhibit a continuous series of extremely bright flares. Astronomers will exploit them to investigate the mechanisms that give rise to powerful jets of particles, moving away at velocities close to the speed of light, from the black hole’s accretion disk.

There are only a handful of black hole binary systems for which data have been collected simultaneously at many wavelengths, and the current outburst of V404 Cygni offers the rare chance to gather more observations of this kind. Back in space, Integral has a full-time job watching the events unfold.

“We have been devoting all of Integral’s time to observe this exciting source for the past week, and we will keep doing so at least until early July,” comments Peter Kretschmar from ESA.

“The observations will soon be made available publicly so that astronomers across the world can exploit them to learn more about this unique object. It will also be possible to use Integral data to try and detect polarization of the X-ray and gamma-ray emission, which could reveal more details about the geometry of the black hole accretion process. This is definitely material for the astrophysics textbooks for the coming years.”