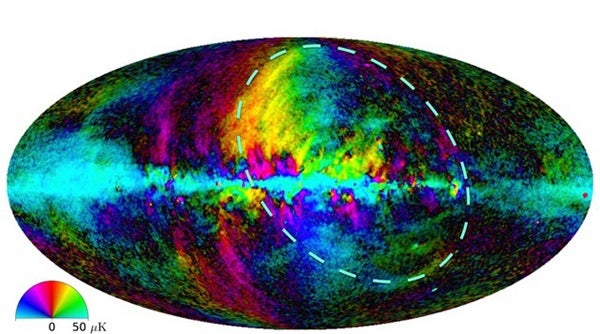

The European Space Agency’s (ESA) Planck satellite, launched in 2009 to study the ancient light of the Big Bang, has also given us maps of our Milky Way Galaxy in microwaves (radiation at centimeter to millimeter wavelengths). Microwaves are generated by electrons spiraling in the galaxy’s magnetic field at nearly the speed of light — the synchrotron process: by collisions in interstellar plasma, by thermal vibration of interstellar dust grains, and by “anomalous” microwave emission (AME), which may be from spinning dust grains.

The new maps show regions covering huge areas of our sky that produce AME. This process, only discovered in 1997, could account for a large amount of galactic microwave emission with a wavelength near 0.4 inch (1 centimeter). One example where it is exceptionally bright is the 200-light-year-wide dust ring around the Lambda Orionis Nebula — the “head”’ of the familiar Orion constellation. This is the first time the ring has been seen in this way.

A wide-field map also shows synchrotron loops and spurs where charged particles spiral around magnetic fields, including the huge Loop 1 that was discovered more than 50 years ago. Remarkably, astronomers are still uncertain about its distance. It could be anywhere between 400 and 25,000 light-years away, and though it covers around a third of the sky, it is impossible to say exactly how big it is.