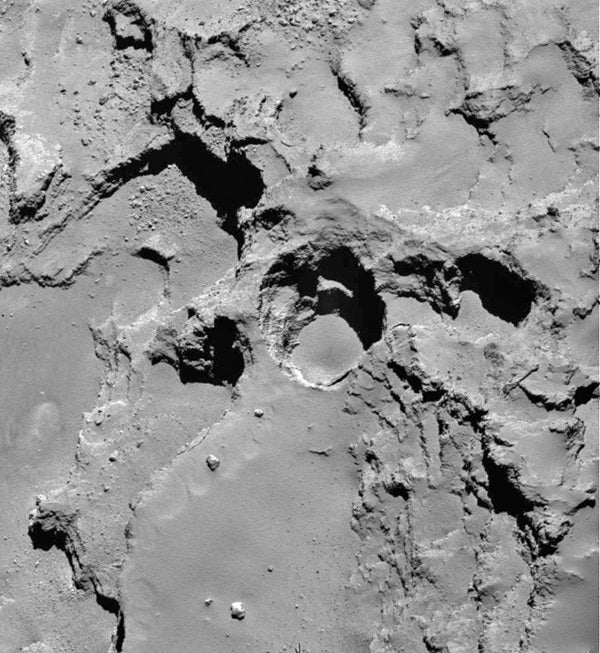

The study reveals that the surface of Comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko is variable and dynamic, undergoing rapid structural changes as it approaches the Sun. Far from simple balls of ice and dust, comets have their own life cycles. The latest findings are among the first to show, in detail, how comets change over time.

“These strange circular pits are just as deep as they are wide. Rosetta can peer right into them,” said Dennis Bodewits from the University of Maryland in College Park. The pits are large, ranging from tens of meters in diameter up to several hundred meters across.

“We propose that they are sinkholes, formed by a surface collapse process very similar to the way sinkholes form here on Earth,” Bodewits added. Sinkholes occur on Earth when subsurface erosion removes a large amount of material beneath the surface, creating a cavern. Eventually the ceiling of the cavern will collapse under its own weight, leaving a sinkhole behind. “So we already have a library of information to help us understand how this process works, which allows us to use these pits to study what lies under the comet’s surface,” Bodewits said.

Bodewits and his team analyzed images from Rosetta’s Optical, Spectroscopic and Infrared Remote Imaging System (OSIRIS) narrow-angle camera, which is designed to image the surface of the comet’s nucleus. The team noted two distinct types of pits: deep ones with steep sides and shallower pits that more closely resemble those seen on other comets, such as 9P/Tempel 1 and 81P/Wild. The team also observed that jets of gas and dust streamed from the sides of the deep steep-sided pits — a phenomenon they did not see in the shallower pits.

Initially, the Rosetta team suspected that discrete explosive events might be responsible for creating the deeper pits. Rosetta observed one such outburst during its approach to the comet on April 30, 2014. Catching this event in the act allowed the team to quantify how much material had been ejected, and it quickly became obvious that the numbers just didn’t stack up. Explosive outbursts alone could not explain the formation of these giant pits.

“The amount of material from the outburst was large — about 100,000 kilograms [220,000 pounds] — but this is small compared to the size of the comet and could only explain a hole a couple of meters in diameter,” Bodewits said. “The pits we see are much larger. It seems that outbursts aren’t driving the process, but instead are one of the consequences.”

Based on the Rosetta observations, the team has proposed a model for the formation of these sinkholes. A source of heat beneath the comet’s surface causes ices — primarily water, carbon monoxide, and carbon dioxide — to sublimate. The voids created by the loss of these ice chunks eventually grow large enough that their ceilings collapse under their own weight, giving rise to the deep steep-sided circular pits seen on the surface of Comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko.

The collapse exposes comet ices to sunlight for the first time, which causes the ice chunks to begin sublimating immediately. These deeper pits are therefore thought to be relatively young. Their shallower counterparts, on the other hand, are most likely older sinkholes with more thoroughly eroded sidewalls and bottoms that have been filled in by dust and ice chunks.

“In some sense, these deep sinkholes remind me of the crater excavated on Comet Tempel I by the Deep Impact mission,” said Michael A’Hearn from the University of Maryland. “The process is completely different, of course, but both allow us to achieve the same broad goal of being able to see deeper into a comet.”

ESA officially extended the Rosetta mission June 23, 2015, meaning that the spacecraft will have the opportunity to track Comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko for a much longer time period as it moves away from the Sun. The comet will reach perihelion, or its closest point to the Sun, on August 13, 2015. The extension expands the mission by nine months, from the planned end date of December 2015 to September 2016. The extra observational time will enable the team to see how the comet’s surface responds to decreasing solar radiation.