Today marks 26 years since NASA made its one and only visit to Neptune. And for years, planetary scientists have bemoaned a predicted 50-year gap between that flyby from Voyager 2 and its next mission.

NASA’s Jim Green took a step toward narrowing that gap today at the Outer Planets Assessment Group meeting in Laurel, Maryland. The agency’s head of planetary sciences announced that the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) will study a flagship mission to Uranus and/or Neptune.

If approved, the spacecraft would be the next big mission following Mars2020 and Europa Clipper (now Europa Multiple Flyby Mission). Green says the proposed flagship mission’s cost should be less than $2 billion. Past flagship missions include Cassini, Galileo, and Voyager.

Argo, the last proposed mission to Neptune, was grounded because NASA didn’t have enough plutonium to power all of its spacecraft, according to one of its designers.

Candice Hansen of the Jet Propulsion Laboratory says there was a special launch window from 2015 to 2020 that would put Argo at Neptune in a decade thanks to gravity assists from Jupiter and Saturn. That timeline is now impossible to meet.

But she says the Space Launch System rocket that NASA is currently building could eliminate the need for gravity assists and get to Uranus or Neptune much faster (though it’s unlikely to prevent the 50-year gap).

Congress, which loves SLS, has pushed NASA to use the massive rocket on their Europa mission. And now that NASA has funding for more plutonium, the space agency says it can once again consider trips to the outer solar system.

However, the decision will be largely up to the planetary scientists who will use the JPL study as they rank priorities in the next decadal survey, which typically determines what receives funding and what does not.

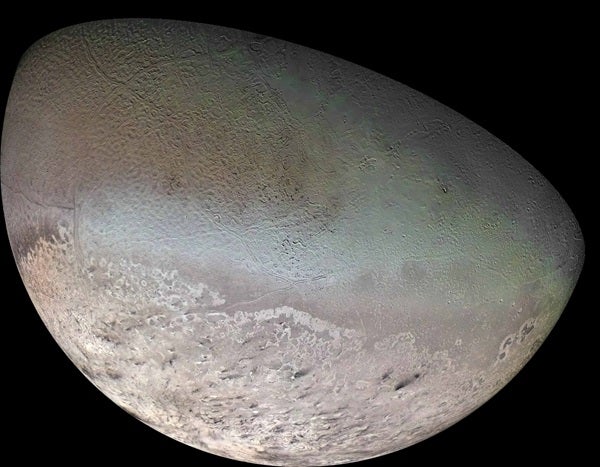

Neptune’s moon Triton is an enticing option for many of the same reasons that prompted the Europa Clipper mission. No other large moon in the solar system has a retrograde orbit. That leads astronomers to suspect Triton is actually a captured Kuiper Belt object — a larger cousin to Pluto. Triton is also nearly as big as Earth’s Moon but has smoke-stack like plumes from ice volcanoes that erupt nitrogen frost onto its surface.

For its part, Uranus has five moons big enough to be considered dwarf planets if they orbited the Sun on their own.

All of this is part of a new larger effort by NASA. Earlier this year, a bill from the House Subcommittee on Commerce, Justice, Science, and Related Agencies directed the space agency to create an Ocean World Exploration Program.

But even with such a push, NASA will soon be without any missions actively exploring planets in the outer solar system.

NASA’s Juno mission is currently headed to study Jupiter’s atmosphere, but it’s scheduled to end by 2018. And the current Cassini mission at Saturn is set to crash into the planet as its fuel runs out in 2017. A Europa flyby spacecraft likely won’t be ready until the mid-2020s.

Eric Betz is an associate editor of Astronomy. He’s on Twitter: @ericbetz.