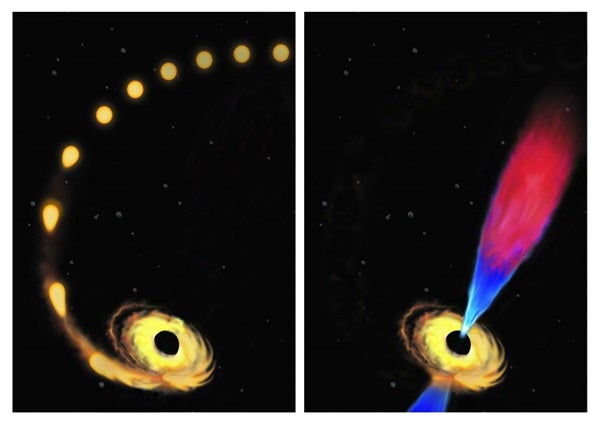

The supermassive black hole was found to have faint jets of material shooting out from it and helps to confirm scientists’ theories about the nature of black holes.

Gemma Anderson from the Curtin University node of the International Center for Radio Astronomy Research (ICRAR) said a supermassive black hole swallowing a star is an extreme event in which the star gets ripped apart.

“It’s very unusual when a supermassive black hole at the center of a galaxy actually eats a star. We’ve probably only seen about 20 of them,” she said.

“Everything we know about black holes suggests we should see a jet when this happens, but until now they’ve only been detected in a few of the most powerful systems. Now we’ve finally found one in a more normal event.”

The discovery is the first time scientists have been able to see both a disk of material falling into a black hole, known as an accretion disk, and a jet in a system of this kind.

James Miller-Jones from ICRAR compared the energy produced by the jets in this event to the entire energy output of the Sun over 10 million years.

He said it was likely all supermassive black holes swallowing stars launched jets, but this discovery was made because the black hole is relatively close to Earth and was studied soon after it was first seen.

The black hole is only 300 million light-years away from us, and the team led by Sjoert van Velzen from The Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, Maryland, was able to make its first observations only three weeks after it was found.

“We’ve shown that it was just a question of looking at the right time and with enough sensitivity,” Miller-Jones said. “Then you can show that a jet exists right at the point you think it should.”

Anderson began the research while working with the 4 PI SKY team at Oxford University but moved to Western Australia in September.

She said the event was first picked up by the All-sky Automated Survey for Supernovae (ASAS-SN), which is pronounced “assassin” by astronomers, and followed up with the Arcminute Microkelvin Imager (AMI), a radio telescope, located near Cambridge.

“Hopefully, with the increased sensitivity of future telescopes like the Square Kilometre Array, we’ll be able to detect jets from other supermassive black holes of this type and discover even more about them,” Anderson said.