Although the spacecraft will continue to observe Enceladus during the remainder of its mission (through September 2017), it will be from much greater distances — at closest, more than four times farther away than the Dec. 19 encounter.

The upcoming flyby will focus on measuring how much heat is coming through the ice from the moon’s interior — an important consideration for understanding what is driving the plume of gas and icy particles that sprays continuously from an ocean below the surface.

“Understanding how much warmth Enceladus has in its heart provides insight into its remarkable geologic activity, and that makes this last close flyby a fantastic scientific opportunity,” said Linda Spilker, Cassini project scientist at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Pasadena, California.

By design, the encounter will not be Cassini’s closest. The flyby was designed to allow Cassini’s Composite Infrared Spectrometer (CIRS) instrument to observe heat flow across Enceladus’ south polar terrain.

“The distance of this flyby is in the sweet spot for us to map the heat coming from within Enceladus — not too close, and not too far away. It allows us to map a good portion of the intriguing south polar region at good resolution,” said Mike Flasar, CIRS team lead at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, Greenbelt, Maryland.

The south polar region of Enceladus, while well lit for observing observations by Cassini’s visible light cameras when the spacecraft arrived at Saturn in mid-2004, is presently in the darkness of the years-long Saturnian winter. The absence of heat from the Sun makes it easier for Cassini to observe the warmth from Enceladus itself. By the time the mission concludes, Cassini will have obtained observations over six years of winter darkness in the moon’s southern hemisphere.

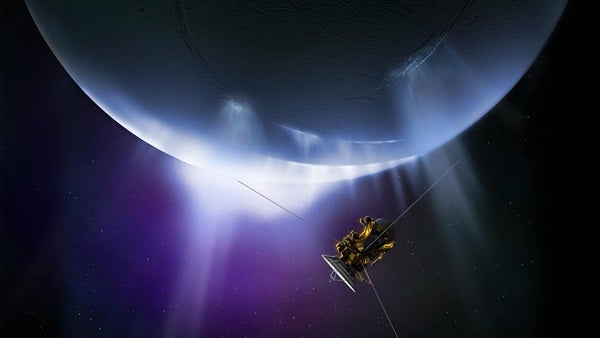

Cassini completed a daring dive through the moon’s erupting plume on Oct. 28, passing just 30 miles (49 kilometers) above the surface. Scientists are still analyzing data collected during that encounter to better understand the nature of the plume, its particles and whether hydrogen gas is present — the latter would be an independent line of evidence for active hydrothermal systems in the seafloor.

This moderately close flyby will be the 22nd of Cassini’s long mission. The spacecraft’s surprising discovery of geologic activity on Enceladus, not long after arriving at Saturn, prompted changes to the mission’s flight plan in order to maximize the number and quality of encounters with the icy moon. Cassini made its closest Enceladus flyby on Oct. 9, 2008, at an altitude of 16 miles (25 kilometers).

The unfolding story of Enceladus has been one of the great triumphs of Cassini’s historic mission at Saturn. Scientists first detected signs of the moon’s icy plume in early 2005, followed by a series of discoveries about the material gushing from warm fractures near its south pole. They announced strong evidence for a regional subsurface sea in 2014, revising their understanding in 2015 to confirm that the moon hosts a global ocean beneath its icy crust.

“Cassini’s legacy of discoveries in the Saturn system is profound,” said Spilker. “We won’t get this close to Enceladus again with Cassini, but our travels have opened a path to the exploration of this and other ocean worlds.”