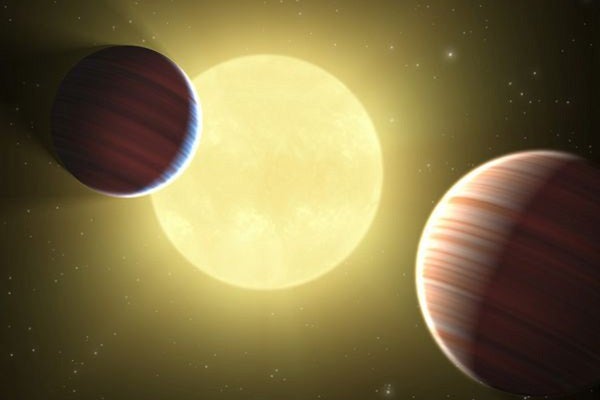

In our galaxy, there may be billions of planetary systems where more than one planet is habitable. NASA’s Kepler spacecraft has found planet pairs on very similar orbits, with orbital distances differing by as little as 10 percent. If such a planet pairing occurred in the right place, then both planets could sustain life and even help each other along.

Steffen and Gongjie Li from the Harvard Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics in Cambridge, Massachusetts, studied some of the ramifications for life in these multihabitable systems.

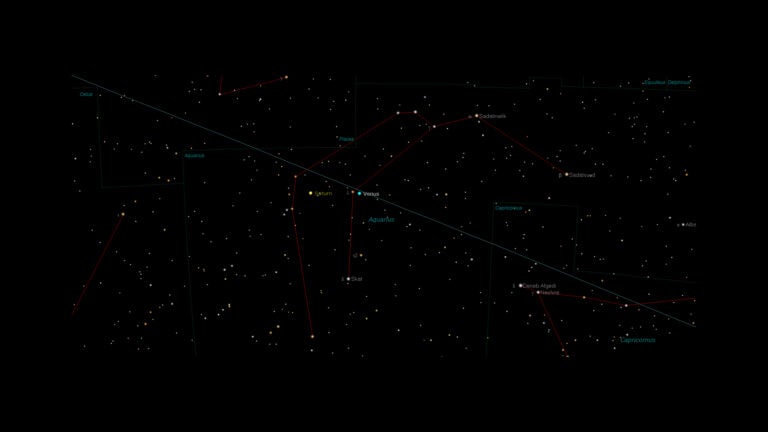

“It’s pretty intriguing to imagine a system where you have two Earth-like planets orbiting right next to each other,” said Steffen. “If some of these systems we’ve seen with Kepler were scaled up to the size of the Earth’s orbit, then the two planets would only be one-tenth of one astronomical unit apart at their closest approach. That’s only 40 times the distance to the Moon.”

Mars, at best, is 200 times the lunar distance, he noted.

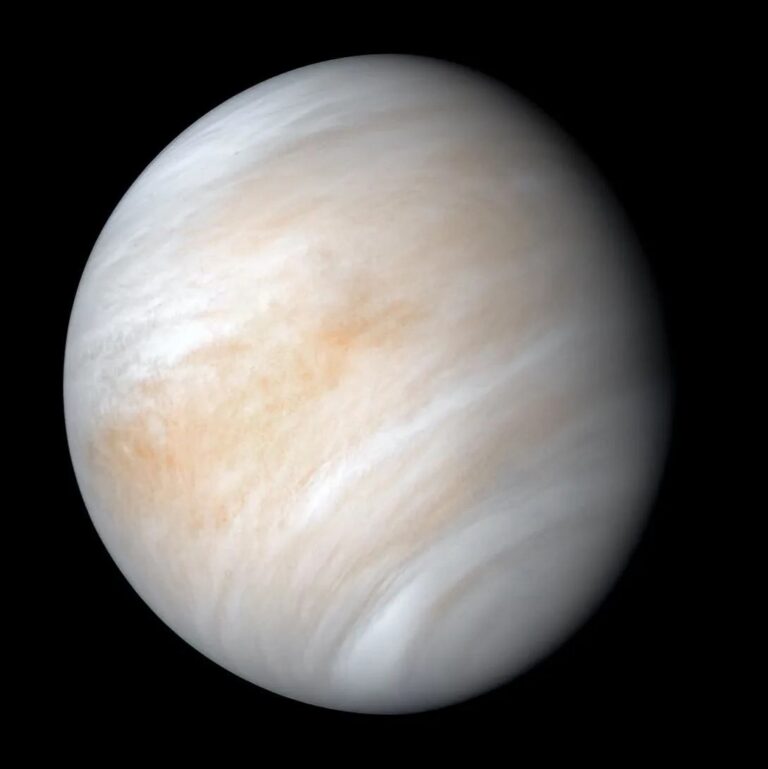

With planets so close together, a number of interesting processes become important. For one, the seasons on Earth, and Earth’s climate in general, depend upon its “obliquity,” or the 23.5° tilt of Earth’s axis relative to its orbit. A change of only a few degrees could cause a permanent ice age. If two planets on neighboring orbits caused large changes in each other’s obliquities, then their climates would not be stable.

“We found that the obliquities of the planets in multihabitable systems were not really affected by their close orbits,” said Li. “Only in rare instances would their climates be altered in dramatic ways. Otherwise, their behavior was similar to the planets in the solar system.”

Another process that the scientists investigated was lithopanspermia — the means by which life-bearing material on one planet can be ejected by meteor impacts and delivered to the surface of another planet. For example, on Earth more than 100 meteorites of martian origin have been found. Steffen and Li identified a number of facts that would facilitate the proliferation of life between two planets in a multihabitable system.

First, the energy of the impact needed to get material from one planet to another in a multihabitable system is much less than it is in the solar system, so microorganisms are more likely to survive the impact itself. Second, the time needed to traverse the interplanetary distance is much smaller. And third, the way that the impact debris travel through space (flowing in streams) implies that it is more likely that material from a single impact could hit the destination planet at multiple locations in relatively rapid succession. This scenario would increase the chances of life gaining a foothold.

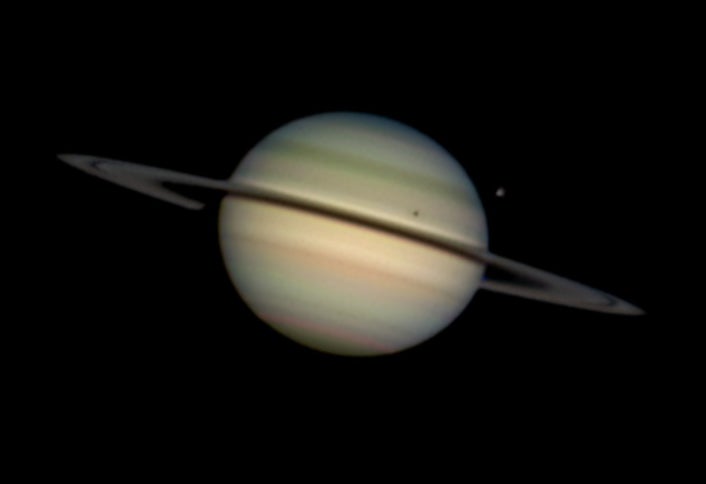

“Multihabitable systems could have a microbial family tree with roots and branches simultaneously on two different planets,” Steffen said. “Systems like those that we investigated and moon systems orbiting a habitable-zone giant planet are among the few scenarios where life — intelligent life in particular — could exist in two places at the same time and in the same system.”

And their neighborliness would foster communication, he said.

“You can imagine that if civilizations did arise on both planets, they could communicate with each other for hundreds of years before they ever met face-to-face. It’s certainly food for thought.”

Despite the challenges that life may have in developing on a planet, it appears that the presence of a nearby companion in the struggle may help. “At least the climate isn’t likely to be any worse in multihabitable systems, and the possibility of two planets sharing the biological burden could help the system traverse the inevitable rough times,” Steffen said.