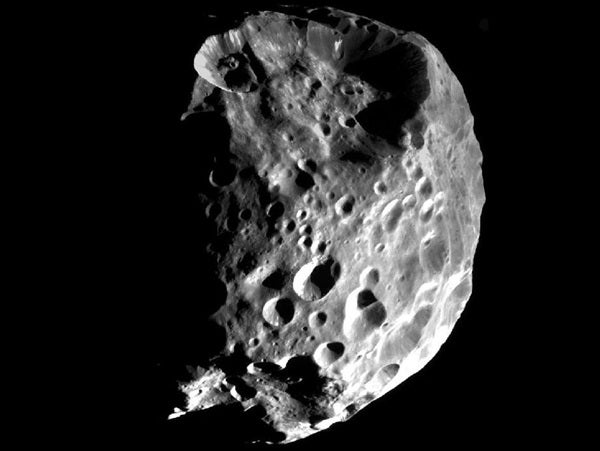

The giant comets, termed Centaurs, move on unstable orbits crossing the paths of the massive outer planets Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune. The planetary gravitational fields can occasionally deflect these objects in towards Earth.

Centaurs are typically 30–60 miles (50–100 kilometers) across, or larger, and a single such body contains more mass than the entire population of Earth-crossing asteroids found to date. Calculations of the rate at which Centaurs enter the inner solar system indicate that one will be deflected onto a path crossing Earth’s orbit about once every 40,000–100,000 years. While in near-Earth space, they are expected to disintegrate into dust and larger fragments, flooding the inner solar system with cometary debris and making impacts on our planet inevitable.

Known severe upsets of the terrestrial environment and interruptions in the progress of ancient civilizations, together with our growing knowledge of interplanetary matter in near-Earth space, indicate the arrival of a Centaur around 30,000 years ago. This giant comet would have strewn the inner planetary system with debris ranging in size from dust all the way up to lumps several kilometers across.

Specific episodes of environmental upheaval around 10,800 BCE and 2,300 BCE, identified by geologists and paleontologists, are also consistent with this new understanding of cometary populations. Some of the greatest mass extinctions in the distant past, for example the death of the dinosaurs 65 million years ago, may similarly be associated with this giant comet hypothesis.

Napier comments: “In the last three decades, we have invested a lot of effort in tracking and analyzing the risk of a collision between Earth and an asteroid. Our work suggests we need to look beyond our immediate neighborhood too and look out beyond the orbit of Jupiter to find Centaurs. If we are right, then these distant comets could be a serious hazard, and it’s time to understand them better.”

The researchers have also uncovered evidence from disparate fields of science in support of their model. For example, the ages of the submillimeter craters identified in lunar rocks returned in the Apollo program are almost all younger than 30,000 years, indicating a vast enhancement in the amount of dust in the inner solar system since then.