Key Takeaways:

Until now, the biggest supermassive black holes — those roughly 10 billion times the mass of our Sun —have been found at the cores of large galaxies in regions of the universe packed with other large galaxies. In fact, the current record holder tips the scale at 21 billion Suns and resides in the crowded Coma Galaxy Cluster, which consists of over 1,000 galaxies.

“The newly discovered super sized black hole resides in the center of a massive elliptical galaxy, NGC 1600, located in a cosmic backwater, a small grouping of 20 or so galaxies,” said Chung-Pei Ma from the University of California, Berkeley. While finding a gigantic black hole in a massive galaxy in a crowded area of the universe is to be expected – like running across a skyscraper in Manhattan – it seemed less likely they could be found in the universe’s small towns.

“There are quite a few galaxies the size of NGC 1600 that reside in average-sized galaxy groups,” Ma said. “We estimate that these smaller groups are about 50 times more abundant than spectacular galaxy clusters like the Coma cluster. So the question now is, ‘Is this the tip of an iceberg?’ Maybe there are more monster black holes out there that don’t live in a skyscraper in Manhattan, but in a tall building somewhere in the Midwestern plains.”

The researchers also were surprised to discover that the black hole is 10 times more massive than they had predicted for a galaxy of this mass. Based on previous Hubble surveys of black holes, astronomers had developed a correlation between a black hole’s mass and the mass of its host galaxy’s central bulge of stars — the larger the galaxy bulge, the proportionally more massive the black hole. But for galaxy NGC 1600, the giant black hole’s mass far overshadows the mass of its relatively sparse bulge. “It appears that that relation does not work very well with extremely massive black holes; they are a larger fraction of the host galaxy’s mass,” Ma said.

Ma and her colleagues are reporting the discovery of the black hole, which is located about 200 million light-years from Earth in the direction of the constellation Eridanus, in the April 6 issue of the journal Nature.

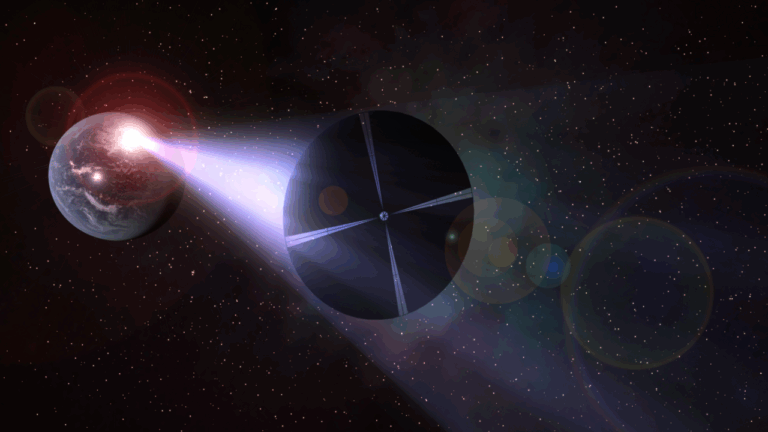

One idea to explain the black hole’s monster size is that it merged with another black hole long ago when galaxy interactions were more frequent. When two galaxies merge, their central black holes settle into the core of the new galaxy and orbit each other. Stars falling near the binary black hole, depending on their speed and trajectory, can actually rob momentum from the whirling pair and pick up enough velocity to escape from the galaxy’s core. This gravitational interaction causes the black holes to slowly move closer together, eventually merging to form an even larger black hole. The supermassive black hole then continues to grow by gobbling up gas funneled to the core by galaxy collisions. “To become this massive, the black hole would have had a very voracious phase during which it devoured lots of gas,” Ma said.

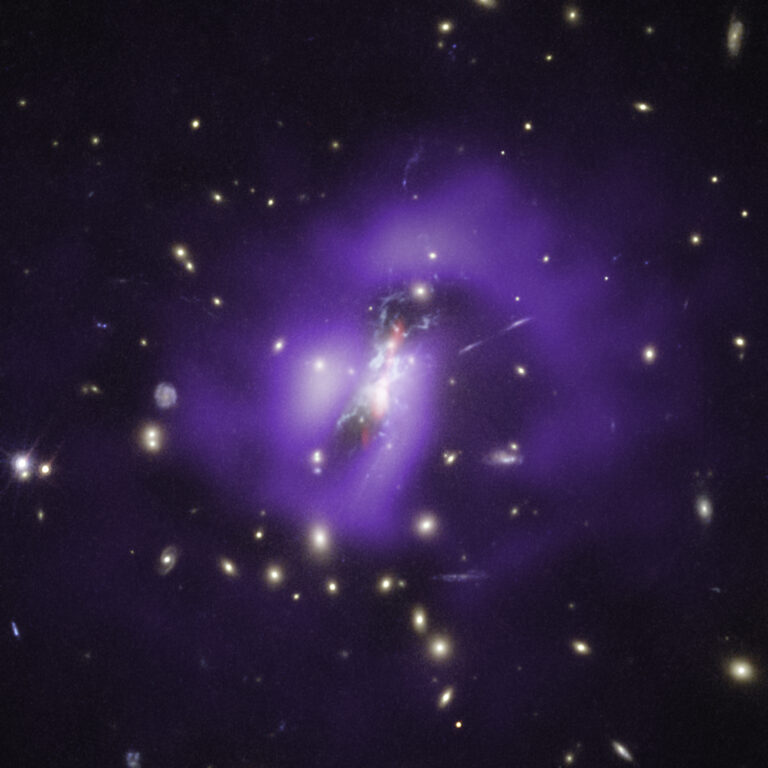

The frequent meals consumed by NGC 1600 may also be the reason why the galaxy resides in a small town with few galactic neighbors. NGC 1600 is the most dominant galaxy in its galactic group, at least three times brighter than its neighbors. “Other groups like this rarely have such a large luminosity gap between the brightest and the second brightest galaxies,” Ma said.

Most of the galaxy’s gas was consumed long ago when the black hole blazed as a brilliant quasar from material streaming into it that was heated into a glowing plasma. “Now, the black hole is a sleeping giant,” Ma said. “The only way we found it was by measuring the velocities of stars near it, which are strongly influenced by the gravity of the black hole. The velocity measurements give us an estimate of the black hole’s mass.”

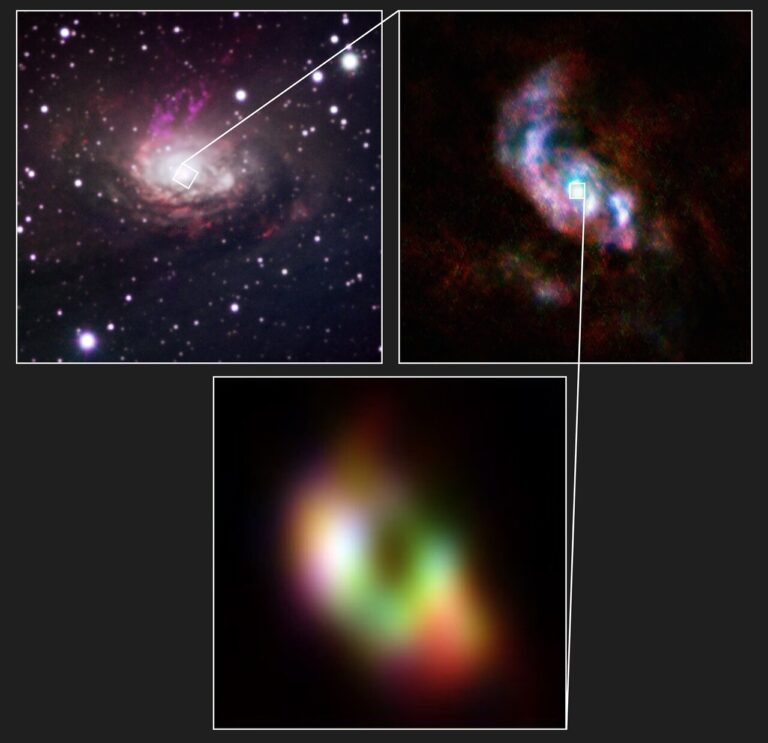

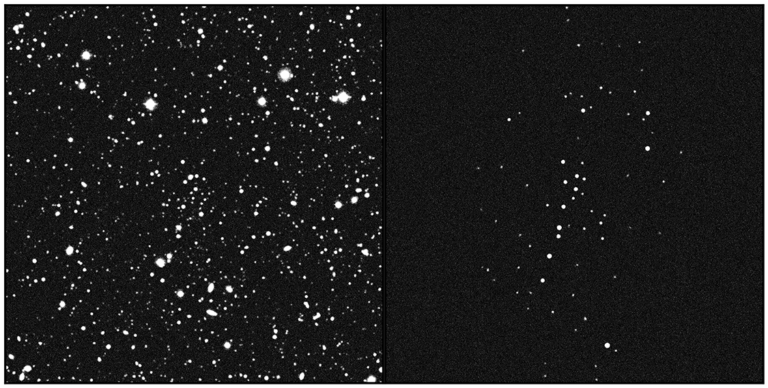

The velocity measurements were made by the Gemini Multi-Object Spectrograph (GMOS) on the Gemini North 8-meter telescope on Mauna Kea in Hawaii. GMOS spectroscopically dissected the light from the galaxy’s center, revealing stars within 3,000 light-years of the core. Some of these stars are circling around the black hole and avoiding close encounters. However, stars moving on a straighter pathway from the core suggest that they had ventured closer to the center and had been slung away, most likely by the twin black holes.

Archival Hubble images, taken by the Near Infrared Camera and Multi-Object Spectrometer (NICMOS), support the idea of twin black holes pushing stars away. The NICMOS images revealed that the galaxy’s core was unusually faint, indicating a lack of stars close to the galactic center. A star-depleted core distinguishes massive galaxies from standard elliptical galaxies, which are much brighter in their centers. Ma and her colleagues estimated that the amount of stars tossed out of the central region equals 40 billion Suns, comparable to ejecting the entire disk of our Milky Way Galaxy.