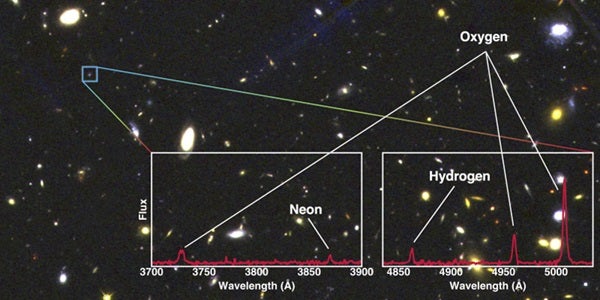

Using the Multi-Object Spectrograph for Infrared Exploration (MOSFIRE) instrument installed on the Keck I telescope, the scientists gathered data on 41 normal star-forming galaxies that were 11 billion light-years away.

The team found typical galaxies forming stars in the universe two billion years after the Big Bang have only twenty percent of metals — elements heavier than Helium — compared with those in the present day universe. They also discovered the metal content is independent of the strength of the star-formation activity, in stark contrast with what is known for recently formed or nearby galaxies.

“The galaxies we studied are very faint because they are so far away that light needs more than 11 billion years to reach us,” said Masato Onodera, the lead author of the paper. “Therefore, the superb light-gathering ability of the 10-meter Keck Observatory telescope was crucial to accomplish this study.”

Gathering the photons is only part of the job, breaking it down into data that could be analyzed by the team was the job of Keck Observatory’s latest instrument, MOSFIRE.

“MOSFIRE allowed us to observe multiple objects simultaneously with an exquisite sensitivity, enabling us to collect spectra of many galaxies very efficiently,” Onodera said. “We saw a number of spectral features emitted by ionized atoms in the galaxies such as hydrogen, oxygen, and neon, which allowed us to determine the metal content of the galaxies.”

In addition to the telescope time awarded to them through the California Institute of Technology, the team exchanged valuable time on the 8-meter Subaru Telescope, also on Mauna Kea, for enough time on Keck Observatory to complete the research.

Metal content in star-forming galaxies is the result of a complex interplay between gas coming into the galaxy, star formation in the galaxy, and gas outflowing from the galaxy in the cosmological context. How much metal is in the system and whether the correlation between the metal content and star formation activity exists provide important clues to how galaxies evolve in a distant universe.

“If you extrapolate what is known in the local universe, you would have expected a higher metallicity in less active star-forming galaxies than they found,” said Hien Tran from Keck Observatory. “It’s part of the normal stellar and galaxy evolution. Onodera’s team realized the role of star formation is not as strong at great distances as it is at zero. Understanding the interplay between metallicity, star formation rates, and the mass of star forming galaxies will help us better understand galaxy evolution.”

Because the team did not see any influence of the strength of star formation in the metal enrichment in distant galaxies, it is telling that the physical condition regulating star formation in galaxies in the early universe is possibly different from that seen in the present-day universe. This could be related to the fact that star formation rate cannot keep up with the gas accretion rate from the cosmic web.