Japan’s Hitomi space telescope was ready to burn bright. But instead, the X-ray observatory became the second such satellite from JAXA to meet an untimely end.

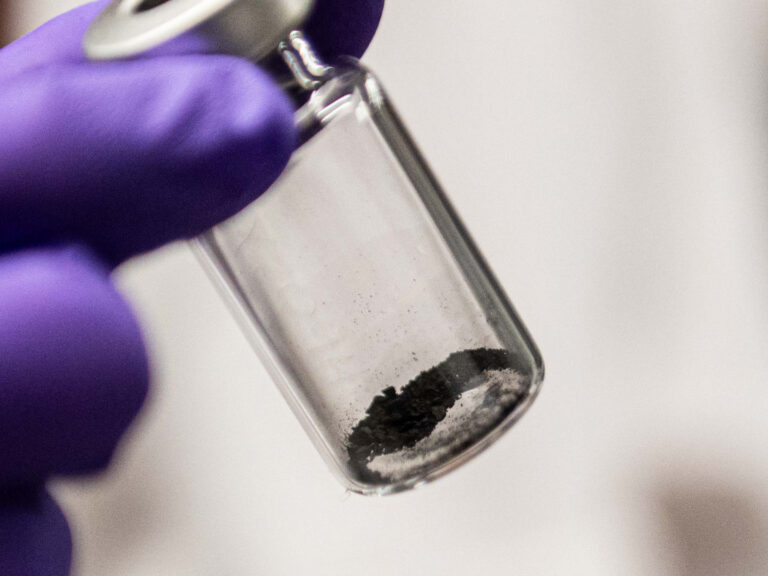

But not all hope is lost. It sent back a sliver of data, and researchers are finding a small cache of treasure in it.

“The suite of observations made were not the full set of what could’ve been delivered,” Roger Blandford, a researcher at SLAC National Accelerator Lab who works on the Hitomi team, said. “Still, in this restricted and limited mode, it showed us what the telescope would have been able to do itself.”

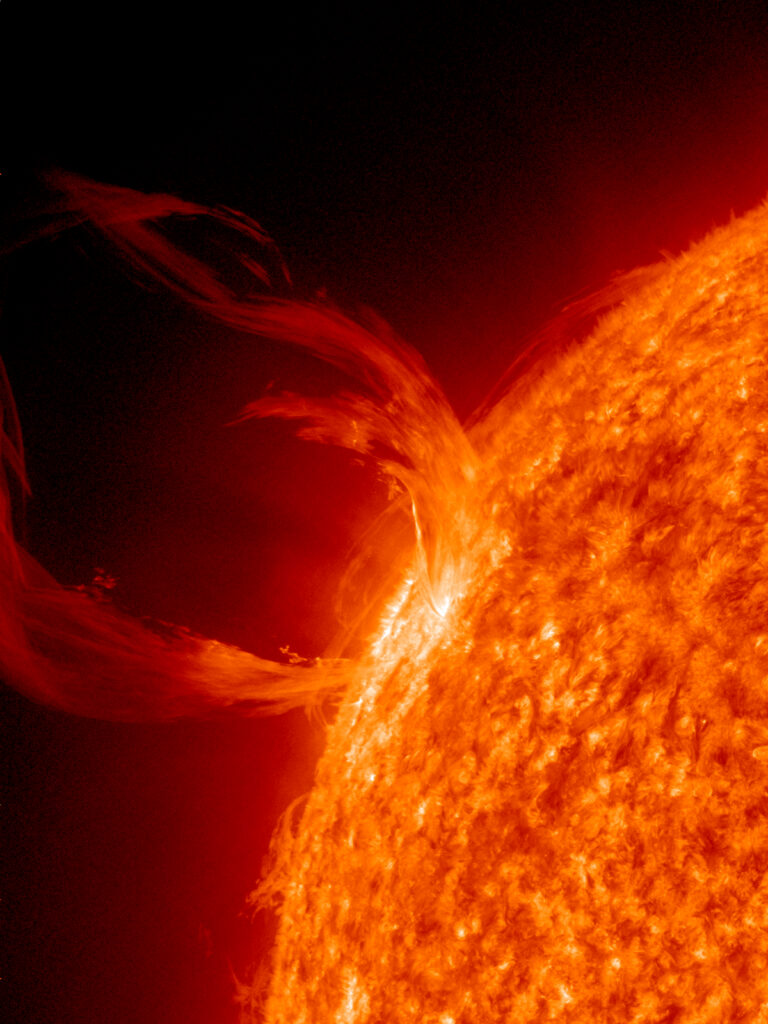

The telescope had begun making observations of the Perseus cluster, a megastructure grouping of galaxies in the universe. While previous X-ray telescopes like NASA’s Chandra have peered at Perseus before, Hitomi looked in fine wavelength spectroscopy, a process involving sussing out the smallest possible details out of light spectra in X-ray which hadn’t been utilized before.

Hitomi was able to spot the churning of hot gases around the core of a supermassive black hole at the center of NGC 1275, a galaxy near the center of the agglomeration of thousands of galaxies. Hitomi scientists were able to determine speed and turbulence of the hot gas, giving a clue as to what’s going on in the center. They discovered that the overall velocity of these gasses is lower than expected, but the data-collecting honeymoon was shortlived.

Hitomi spun out of control in March this year, breaking into several fragments. Ground controllers determined the initial cause to be a software error that gave a velocity reading where there was none, and attempts to compensate for this attitude problem resulted in uncontrolled spin and total mission failure.

While no instrument is capable of sufficient follow-up, Blandford says Hitomi’s limited results open the door to high resolution X-ray spectroscopy.

“It shows so clearly that there’s a signal there to measure,” he says. “Eventually, there will be X-ray satellites like ATHENA and another being discussed. They’ll have this or even better capability, in terms of X-ray spectroscopy.”

Blandford hints that today’s paper (published in Nature) is just one of many coming out from the narrow window of observations Hitomi took in the few days it was up and running. That means that Hitomi’s glimpse was brief, but powerful. And now researchers are hungry for more.

“I hope that one way or another, that can happen sooner than later, because we now know there’s a world of astronomy to explore out there,” Blandford says.