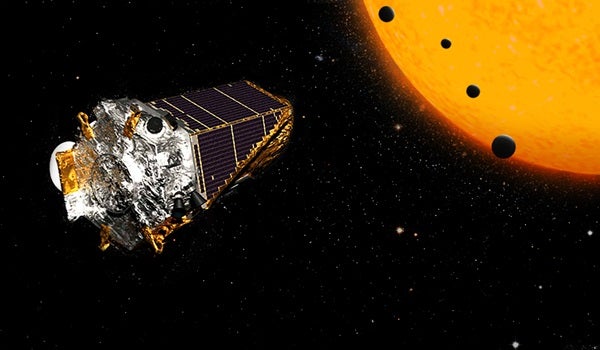

NASA’s Kepler space telescope is a trooper. Even with a broken positioning system, the telescope just discovered 104 new planets, including four Earth-like planets in the same solar system.

A study published this week in the Astrophysical Journal Supplement Series describes the largest haul of planets so far during K2, Kepler’s second mission. Kepler was originally designed to look at a very tiny area of space, but it was repurposed to look at a wider area when part of its positioning system broke in 2013.

This means K2 looks at smaller, cooler, red dwarf stars than Kepler’s original mission, so it has a better chance of finding Earth-like planets. “The original Kepler mission showed us that stars smaller than the Sun probably have more small planets that orbit around them,” says lead author Ian Crossfield of the University of Arizona. “But Kepler only looked at a relatively small number of these small, cool, red stars. K2 is looking at 10 or 20 times as many of these stars.”

These stars are also the most common kind near us, meaning the planets that orbit them are easier to study in more detail.

Perhaps the most interesting treasures in this trove are four roughly Earth-sized planets located in the same solar system 181 light years from us. Based on the planets’ size, between 20 and 50 percent larger than Earth, they are probably rocky. Two of the planets probably get light radiation levels similar to Earth’s. The solar system’s star, an M dwarf star called K2-72, is dimmer than our Sun and about half its size. The four planets are even closer to their star than Mercury is to ours, so their years are each much shorter than Earth’s, ranging from five-and-a-half days to 24 days long.

Nothing is known about the four planets’ atmospheres so far, but from their size, it’s not impossible that life could be found there.

These 104 planets are just from K2’s first year of operations. K2 will last for 4 years, so “we should expect something like four times as many of these planets” over the whole mission, says Crossfield.

Astronomers have confirmed K2’s observations with Earth-based telescope observations and are currently studying some of the planets further—their atmospheres via the Hubble Space telescope, and their masses and densities via Doppler spectroscopy measurements from ground-based telescopes.

The James Webb space telescope, launching in a year and a half, will be able to fill in even more details. “K2 merely tells us a planet is there and its size is roughly this,” says Crossfield. “Whereas James Webb will be able to discern the atmospheric makeup of these things, tell us how much water vapor, or methane, or carbon dioxide, or other molecular species are in the atmosphere, maybe how did they form, what are conditions like, what’s the weather like on other worlds.”