TRAPPIST-1 may well be one of the closest stars to look for life in our own backyard, thanks to three planets in its habitable zone.

Now, we’re one step closer to understanding if those planets could hold life, thanks to a new study published today in Nature.

Using data gathered from the Hubble Space Telescope, researchers at MIT witnessed two occultation events from the innermost planets, TRAPPIST-1b and 1c. The two had near-simultaneous transit events on May 4, 2016 just 12 minutes apart, and some spectrum was gathered from the transit.

Through this, the MIT team made the first atmospheric observation of an Earth-mass planet, and determined the atmosphere of both planets lacked a “gas envelope” of hydrogen and helium around them.

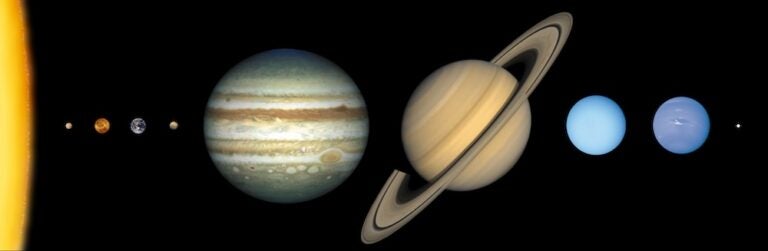

That means that the planets don’t belong to a strange class of planets called gas dwarfs, which is exactly what it sounds like: a mini-mini-Jupiter. They often are terrestrial planets enveloped in a thick atmosphere with a similar composition to Saturn or Jupiter.

“If they were to have such an atmosphere, then they would not be habitable,” says Julien de Wit, lead author of the study and an MIT postdoc. He coauthored the paper announcing the initial discovery of TRAPPIST-1’s system in a May Nature paper.

By ruling out the gas dwarf scenario, the researchers can now home in on more specific details of these two planets. This includes determining if they have atmospheres that are dense and Venus-like or filled with water vapor, which would place them as more Earth-like. There’s also the possibility that, like Mercury, the planets lack anything more than an incredibly thin exosphere.

Some of the really detailed observations of the system, which is is just 39 light years away from Earth, will have to wait for the 2018 launch of the James Webb Space Telescope, which will characterize the atmospheres of Earth-like planets in detail.

In the meantime, de Wit and colleagues will have to rely on data from Hubble, which can still be used to to determine key characteristics like the presence of water or methane. While they might not get as lucky as a two-for-one transit next time, it still could reveal if TRAPPIST-1’s planets contain the ingredients for life.

“What occurred on May 4 was a very rare event,” says de Wit.