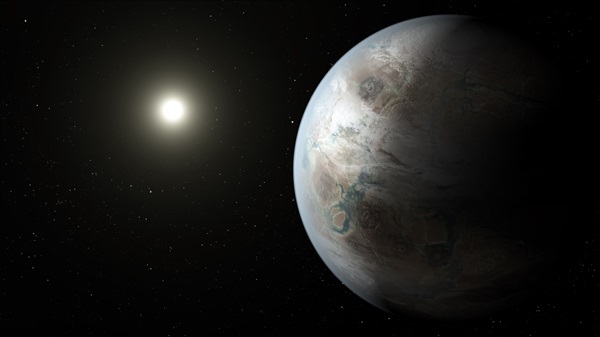

Every time astronomers discover another exoplanet, the first thing we all want to know is “Does it look like Earth?” Finding an Earth-like exoplanet would dramatically increase our chances of finding life as we know it there, and could finally prove that we’re not all alone in this big, cold universe.

But, when we see planets described as Earth-like, we should be skeptical. With our current instruments, it’s hard for us to even find that other planets are out there (although it’s gotten much easier), much less see if there are oceans and atmospheres and trees and Taco Bells. Furthermore, what does it even mean to be “Earth-like?” Does it just need to be in the habitable zone? Or does it need to have liquid water and a similar atmosphere and maybe also be undergoing catastrophic climate change to qualify as being “like” Earth?

Don’t Hold Your Breath

The question likely won’t be resolved anytime soon, because we won’t be able to determine most of these things for quite awhile. While some progress is being made on using the starlight that filters through a planet’s atmosphere to detect what kinds of gases are there, that’s about as precise as we’re going to get for awhile. When, and if, the Breakthrough Starshot mission ever succeeds in reaching Alpha Centauri, we might have a better idea, but even that mission is decades off. So, for now, let’s put off calling planets Earth-like. Unfortunately, we really have no way of knowing exactly how alike they are to our own precious planet.

We are currently limited to just a few solid observations about planets outside of our solar system, and even those can be tough to glean. The three pieces of information we can obtain with any kind of reliability are the mass of the planet, its orbital period, and how far it orbits from its star. These may seem paltry compared with the detailed measurements we’re able to return from Venus or Mars, but astronomers can still derive important information about a planet just by knowing how big and far away it is.

How We Know What We Know

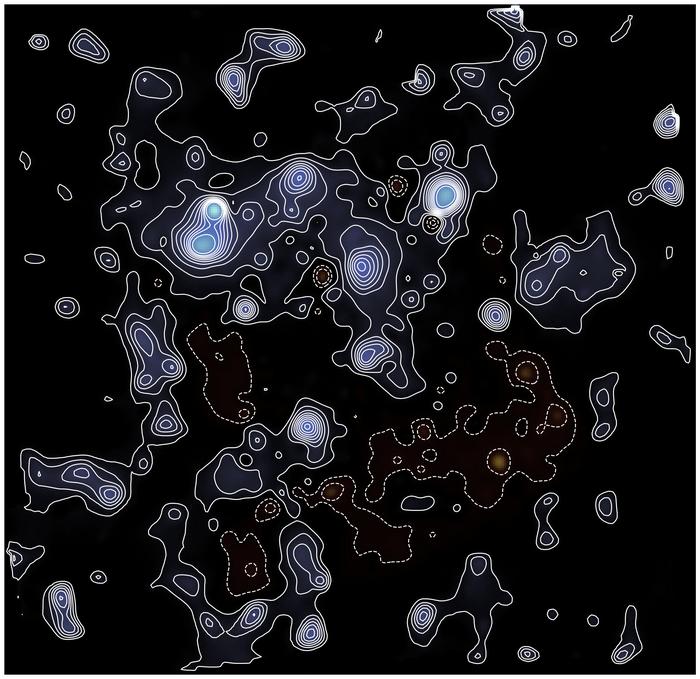

To determine the mass of an exoplanet, astronomers usually look to the star it orbits to measure tiny back-and-forth movements caused by the planet’s gravitational pull as it orbits. We should remember that mass and size are different though, and we have no real way to measure size right now — the best we can do is run an approximation based on the mass. To figure out how fast it rotates, all astronomers have to do is watch and see how often the light of the star dims when the planet passes in front of it. Combining this information with the mass of the star, we can figure out how far away the exoplanet should be, and whether that places it in the habitable zone of a star or not.

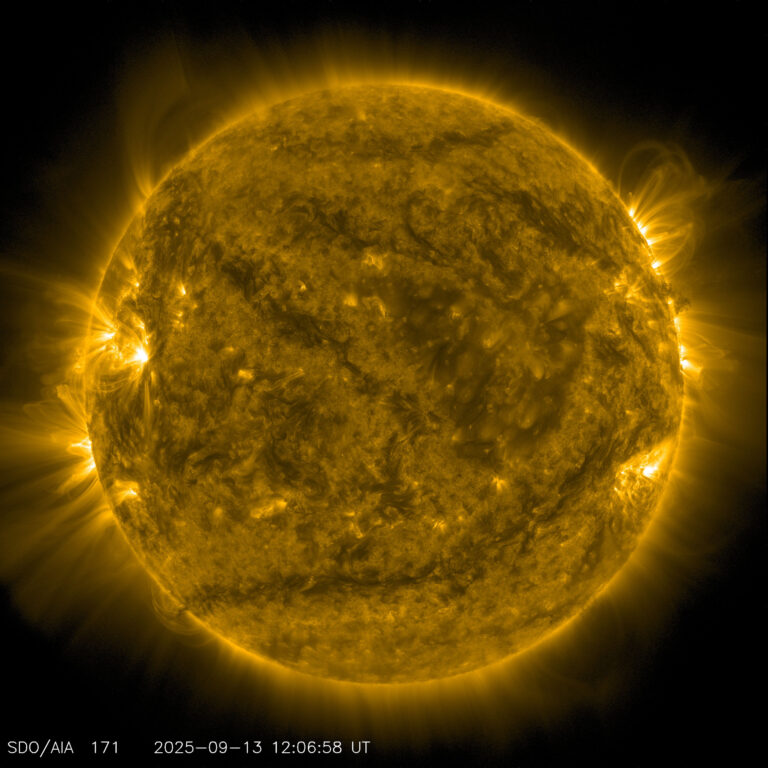

Being in the habitable zone, the small ring around a star where temperatures could allow liquid water to exist, is one of the biggest tests we can do right now for astronomers to determine if a planet could support life or not. If a planet lives outside of that thin ring, the chances of finding life there are pretty much zero.

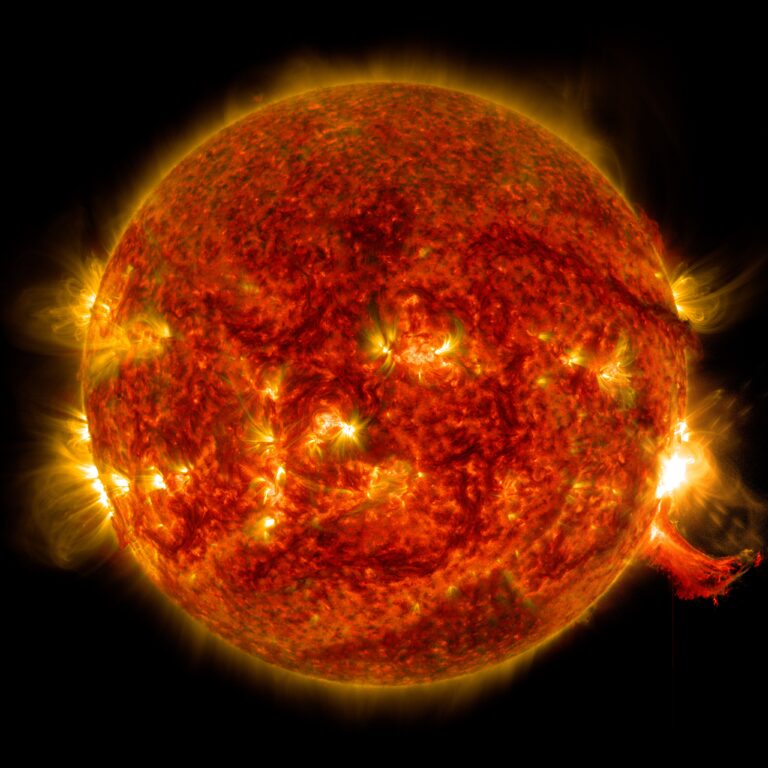

While the habitable zone of a star may be the first hurdle for a planet to overcome on the path to being like Earth, it’s far from the last. Just because liquid water could exist there, doesn’t mean it actually does. The planet could be full of toxic minerals too, or a complete wasteland. It’s core, the internal dynamo that powers our radiation-deflecting magnetic field here on Earth, could be dead, or it could have lost its atmosphere. It could be blasted by waves of powerful radiation from its star, or it could have been assaulted by asteroids. Point is, there are lots of reasons why a potentially exciting exoplanet could be uninhabited, and our methods of observation aren’t refined enough to explore most of those reasons. Calling an exoplanet “Earth-like” is a little too much of a stretch at this point.

There are lots (and lots and lots and lots) of exoplanets out there though, and we’re only to find more. There’s no reason that we won’t find a planet that looks very much like Earth someday. We’re just going to have to wait awhile.