Today, the Red Planet is a dry, dusty landscape devoid of hospitable environments, but the Mars of yesteryear, evidence suggests, was a far more forgiving place.

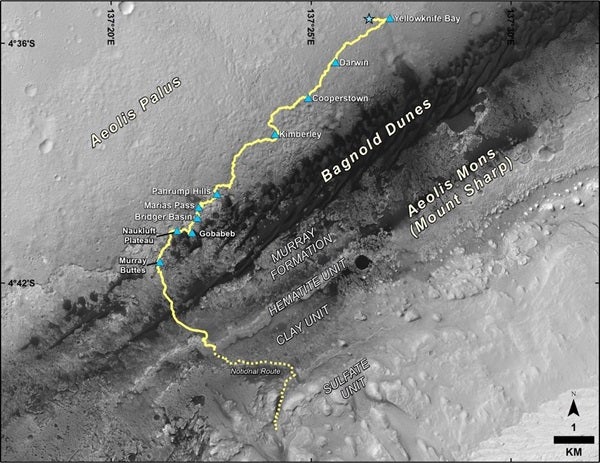

Recent findings from the Curiosity rover indicate that the clay and mineral deposits on the higher regions of Mount Sharp were ideal for hosting life. The rover regularly takes samples of the soil as it traverses the mountain and also uses its Chem-Cam laser to analyze the composition of rocks that are of particular interest.

Recently, Curiosity discovered something on the Red Planet that’s never been seen before: boron. This finding is of particular interest to scientists because boron is usually found in abundance of groundwater, and where we find water we tend to find life. NASA’s mission, after all, is to always “follow the water.”

The findings were announced this week at the American Geophysical Union conference in San Francisco. John Grotzinger, professor of geology at the California Institute of Technology, is calling this a “jackpot” discovery for the team.

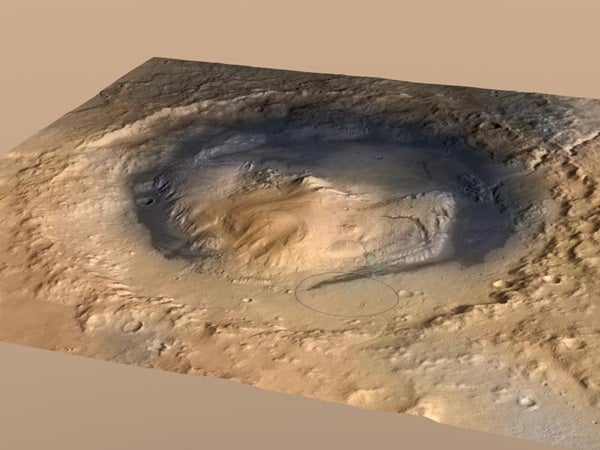

We’ve known for some time that Gale Crater, the site of Curiosity’s mission, was once home to a large lake, but there have been questions as to what Curiosity would find as it ascended Mount Sharp, which rises in the middle of the crater.

Though the team suspected they might find boron on Mars, they were surprised to find it where they did. Boron is usually found in arid climates, where water has long since evaporated, leaving behind a dry arid lakebed. An Earth-type analog for this would be Death Valley in California, where years ago boron was hauled out en masse to be used as detergent — Borax — due to its dissolvability in water.

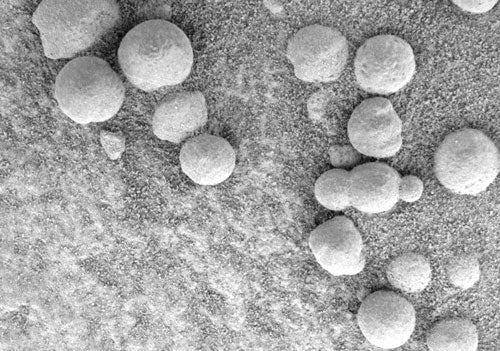

Scientists think boron may have been deposited on Mars after water in Gale Lake evaporated, or could have been transferred into the rock layer from groundwater above. In the same location, Curiosity also found the mineral hematite, which we’ve seen before on Mars from the Opportunity rover in the form of “berries.”

Hematite is iron-rich and is associated with warmer climates. But the discovery of these two at the same geological location could mean something really interesting was happening a few billion years ago.

“Variations in these minerals and elements indicate a dynamic system. They interact with groundwater as well as surface water,” says Grotzinger. “The water influences the chemistry of the clays, but the composition of the water also changes. The more complicated the chemistry is, the better it is for habitability.”

We’ve known that Mars could have once hosted life; after all, the planet still has frozen water on its surface. So how is this finding any more special than the others we’ve heard from Mars?

“When we were at Yellowknife bay we accomplished 99 percent of what we set out to do, but what’s changed is that as we’ve traversed the surface we’ve consistently seen these habitable conditions over time and in different locations across Mars,” says Ashwin Vasavada, project scientist for the Mars Science Laboratory. “This isn’t just in one location, but the last four years we keep coming up with evidence of habitability, and this new complex chemistry really points us to something.”

After four years in operation, Curiosity continues to provide glimpses of what Mars once looked like. And while there’s still no evidence of past life, there are locations throughout Mars that are prime candidates for investigations. Finding the right mineral combinations also indicates that water in Gale Crater might have been drinkable, not too salty, and not too acidic.

In just a few years NASA plans to send a new and improved rover to Mars, but scientists haven’t chosen a landing site for the 2020 rover. Vasavada thinks this new discovery might sway the vote.

“This finding definitely influences, and should influence, how we pick a landing site for both the Mars 2020 rover and a human landing site,” he says.

This article originally appeared on Discover.