Volcanoes may not just exist on moons and planets. A comet orbiting between Saturn and Jupiter seems to have its own signs of icy volcanism, spewing frozen material instead of hot lava. Rather than a single stagnant mound, however, the eruptions come from a single location multiple times before eventually traveling to another point in the icy crust.

The slow rotation of the comet allows the crust to weaken over the course of its day, while carbon monoxide piles up on the surface again during the night. Eventually, the pressure building beneath the surface erupts. Unlike the jets spotted on other comets, the cold ‘lava’ bursts through suddenly and explosively, with no signs of gradual buildup.

“It’s an abrupt event,” says Richard Miles a cometary scientist with the British Astronomical Association who presented the results at the Division for Planetary Sciences meeting in Pasadena, California. Once the explosion is complete, it shuts down without the slow decline common to jets. “It’s done, and everything tapers out. It’s what you would expect from cryovolcanism.”

An active enigma

Comet 29P/Schwassmann-Wachmann is the most active of all known comets. Shortly after its 1927 discovery, the comet’s brightness began to dramatically change. While many comets grow brighter as they travel closer to the sun, 29P orbits in an almost-perfect circle, maintaining a fairly consistent distance from the star. Despite its stable orbit, the comet can make remarkable changes in brightness, making it a favorite for amateur astronomers to observe.

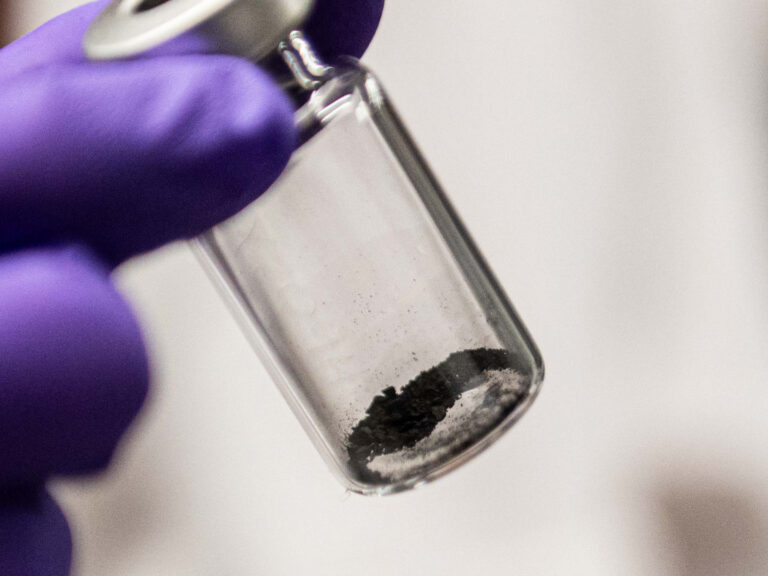

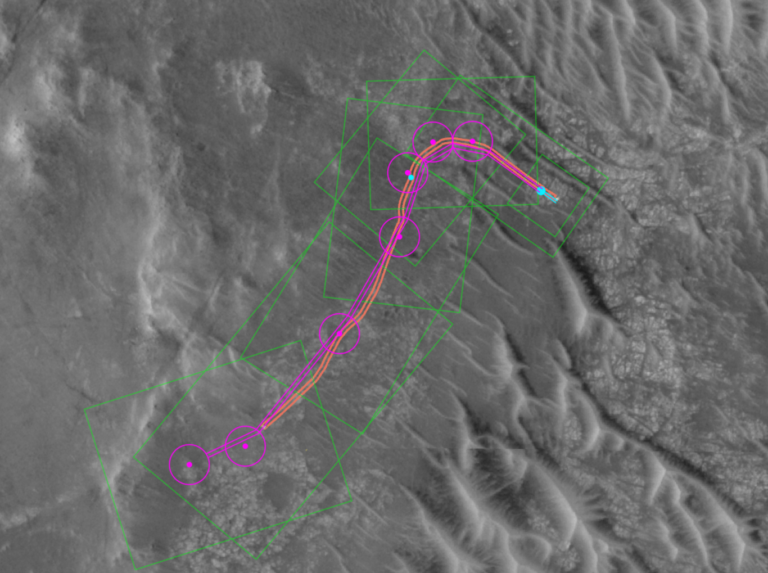

Miles and his colleagues studied the comet over more than a decade, identifying 64 outbursts from the tiny object. The icy body can have as few as three to four outbursts a year, though some years released seven to eight eruptions. By tracking their location over the surface of the comet, the scientists found that many of the eruptions came from the same regions. While some reappeared after a day or so, others took as long as 20 years to reappear, based on earlier observations. It was their repeated appearance that led Miles and his team to dub them as cryovolcanic. Unlike normal volcanoes, which spew molten lava, cryovolcanoes erupt frozen gases that move much like their warmer cousins.

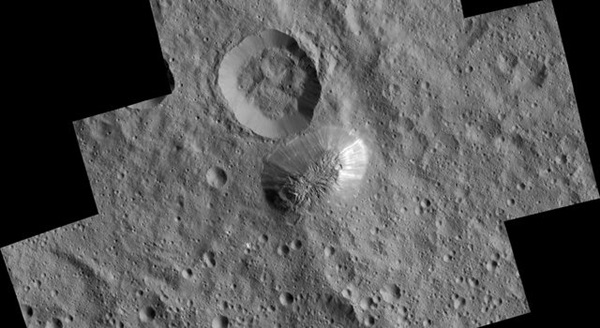

Cryvolcanoes may be common on the icy moons of the solar system, including Jupiter’s moons Europa and Ganymede and Saturn’s moon Titan. Dwarf planets may also host the frigid fountains, as both Pluto and Ceres have features identified as possible cryovolcanoes. Comet 29P doesn’t have features on the ground that resemble icy volcanoes. Instead, Miles interprets the activity as potentially volcanoic.

“If it only appears once, it’s not a volcano,” Miles says. Most of the sites are active two or three times before they run out of steam.

The strange activity may be due to the comet’s unusually long day/night cycle. Unlike most comets, which rotate on hourly scales, 29P rotates only about once every 60 Earth-days. During the comet’s long night, material may pool in chambers beneath the surface. When the comet rotates into its long day, the gas expands, flexing the surface. High pressures can help the gas break through the surface, exploding outward in a volcano-like event. Instead of hot magma, frozen gas streams from the comet.

The material gushing forth behaves a lot like paraffin wax, Miles says. The wax softens long before it melts, or becomes liquid; the same might be true for the material rising up from beneath the comet’s surface. Material around the eruption fissure eventually seals it closed, where it waits until the next time the pressure beneath is strong enough to weaken the surface.

The wax-like material may also trigger other volcanic activity. Thanks to its enormous nucleus, which at about 40 kilometers across is far larger than most other comets, most of the material falls back to the surface. If it lands over other wells of underground material, it may weaken the crust enough to allow them to burst forth as their own volcanoes.

“When you get an outburst, you’re very likely to get a follow-up, or even several,” Miles says.

The resulting material streaming into space as the coma should look different than the bubbles around other comets. “You get this expanding shell,” Miles says. The shell around Comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko, visited by the European Space Agency’s Rosetta mission last year, was far weaker, he says, probably because it formed far less violently.

Despite its unusual activity, Comet 29P has received very little attention from ground- and space-based observatories. Miles hopes to change that as he continues to chronicle the unusual outbursts in an effort to understand the strange cycles on the distant body.

“Effectively, it’s an enigma,” he says.

The research was published in a series of papers the journal Icarus earlier this year.