In 2006, science text books were changed and the hearts of millions broken when the International Astronomical Union decided to give Pluto a new classification: dwarf planet. The logic was to make it fit more with a group of new large objects discovered in the outer solar system, one of which (Eris) is nearly the same size as Pluto. That didn’t prevent outcry.

Indeed, when I attended the New Horizons flyby in 2015, Dava Sobel revealed how the vote might have gone: Pluto and Charon would have been regarded as a double planet, Eris would become a full planet, and Ceres would regain its planetary status. Ceres, from its discovery in 1801 to about the 1850s, was regarded as a planet, as were Vesta, Pallas, and a handful of the other asteroids. As more objects accumulated in that region of the solar system, these small bodies were relegated to minor planet status. Much the same thing happened with Pluto and the Kuiper Belt with each passing discovery.

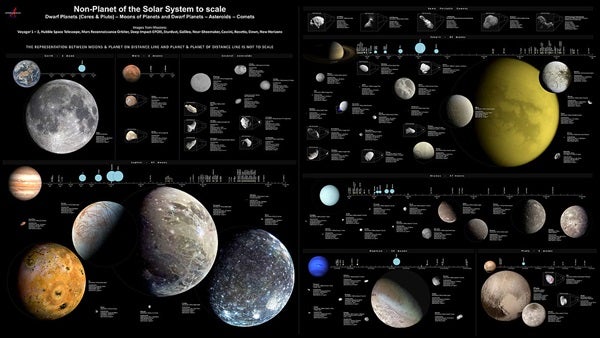

So what did the IAU declare a planet? It had to orbit the Sun (excluding moons), be in a roughly spherical shape (excluding asteroids), and clear its field of debris (excluding the dwarf planets). Had Pluto stayed a planet, and the other large Kuiper Belt Objects come with it, we might have hundreds of planets. To be a dwarf planet, the first two conditions had to be met but the object has to have “failed” at the third. Mike “Pluto killer” Brown currently lists 10 objects as dwarf planets in name or deed, another 20 as more-than-likely, and a total of 148 objects as likely to satisfy the conditions of a dwarf planet.

But Alan Stern, principal investigator of the New Horizons mission, says there’s a better way. In a paper put forth by Stern and others, the definition would be quite simple: “A planet is a sub-stellar mass body that has never undergone nuclear fusion and that has sufficient self-gravitation to assume a spheroidal shape adequately described by a triaxial ellipsoid regardless of its orbital parameters.”

Breaking that down: to be a planet, you have to be large, round, and not a star. As long as a world is rounded out by its own gravity, that makes it a planet.

Which means that in this scenario, the Moon is now a planet. Tiny Enceladus and titanic Titan are both now planets. Pluto is a planet again, but so is Charon. Ceres gains its status back, though most other asteroids do not.

It should be explicitly noted, as not to cause undue headaches: Pluto is not a planet again. This is simply a proposal for something to be considered. The IAU would have to accept the definition, which is definitely not a given. (I will, in the meantime, maintain my planetary-status-agnostic stance.)

I asked Dr. Stern a few questions to figure out what his proposition entailed, and how a moon might become a planet. It may not gain traction, but it does underscore a good point: there’s a lot more to the geology of the solar system than just the currently accepted pantheon of planets.

What, to you, is important about the designation of planet?

As a planetary scientist, it’s important to me that we understand which objects are and are not the objects after which the field is named.

Of objects that have never been considered a planet before, what is the biggest underdog that, to you, was due for a promotion?

The large satellites of planets deserve to be called planets themselves. Just as stars orbit stars, asteroids orbit asteroids, and galaxies orbit galaxies, planets can orbit planets. We see that in binary planets like Pluto-Charon, but also with worlds like the Galilean satellites of Jupiter, Titan and other small planets orbiting Saturn, and our own moon orbiting Earth.

What would you consider the “lower limit” for planetary consideration in our solar system?

The smallest objects that satisfy the geophysical planet definition are about 10 times smaller than Pluto, just at the boundary where rocks turn into bodies made round by their self gravity.

Why do you believe moons should be lumped in with this definition?

Like many planetary scientists, I recognize that these worlds have all the properties of planets, even though they orbit other planets.

It’s been pointed out that you simply want to apply these definitions to our own solar system. How do you see the same principles being used in exoplanet systems, and if this were utilized, would planet encompass all sub-stellar objects (I.e. brown dwarfs)?

Yes, I sure do.

Finally … what do you propose the acronym should be for our new planetary family?

There shouldn’t be such an crayon, there are simply too many planets. Knowing the names of them is, well, so 20th century. We don’t memorize the names of all the mountains or rivers of Earth or all the stars. We only used to be able to do that for planets because our technology was do primitive and we didn’t know there were so many. In the 21st century one only needs to know the names of famous planets, just like kids only have to learn the names of the larges rivers and mountains. Beyond that all you need to know is that there are many more and you can look them up on the web or in books.