While this isn’t the first such suspected “rogue black hole,” it’s currently the most compelling evidence for one. Astronomers have now assembled data from not only HST, but the Chandra X-ray Observatory and the Sloan Digital Sky Survey as well. “The amount of data we collected, from X-rays to ultraviolet to near-infrared light, is definitely larger than for any of the other candidate rogue black holes,” said Marco Chiaberge of the Space Telescope Science Institute (STScI) and Johns Hopkins University in a press release. Chiaberge is the lead author of a paper detailing the observations, which will be published in Astronomy & Astrophysics on March 30.

A quasar is really the disk of dust, gas, and other matter that surrounds a supermassive black hole. As this material clumps and rubs together on its way into the black hole itself, it heats up and shines brightly, allowing astronomers to spot it. (This is because the material is located outside the black hole’s event horizon, inside of which even light cannot escape.) This quasar, named 3C 186, is associated with a distant galaxy that sits about 8 billion light-years away.

Speedy retreat

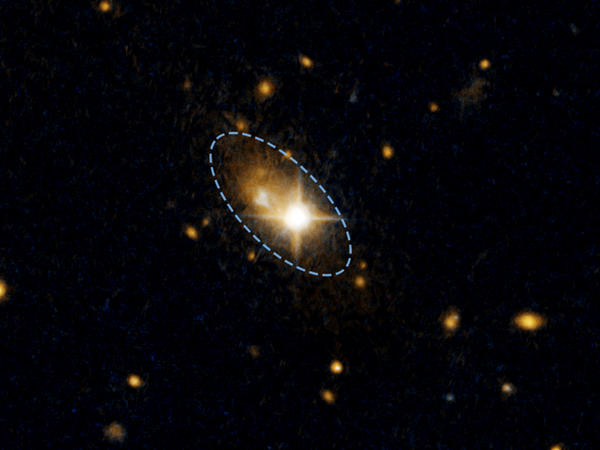

How exactly did astronomers conclude that the object they spotted is a runaway quasar? Using observations from HST in both visible and near-infrared light, the team originally identified the galaxy as an object of interest while completing a survey of galaxies currently undergoing mergers. Chiaberge explained that “I was anticipating seeing a lot of merging galaxies, and I was expecting to see messy host galaxies around the quasars, but I wasn’t really expecting to see a quasar that was clearly offset from the core of a regularly shaped galaxy. Black holes reside in the center of galaxies, so it’s unusual to see a quasar not in the center.”

Once the object had been spotted, the team was able to determine the black hole’s mass and speed based on spectroscopy, which breaks light into many components and allows for the measurement of quantities such as composition and velocity. The black hole’s mass is more than 1 billion Suns, making it the largest such black hole to ever have been detected fleeing the center of its galaxy.

Based on their measurements, “we discovered that the gas around the black hole was flying away from the galaxy’s center at 4.7 million miles an hour (7.6 million kph),” said Justin Ely of STScI, a co-author on the paper. Because the black hole itself cannot be seen, this gas can be used as a proxy for the black hole’s velocity. For a little perspective, an object launched from Earth traveling at that speed could reach the Moon in about three minutes. And if it continues at that speed, in another 20 million years or so, 3C 186 will be free of its galaxy’s gravitational pull, sailing off into intergalactic space.

The team also modeled the starlight in the galaxy to determine how far 3C 186 had traveled thus far, only to find that the black hole is now more than 35,000 light-years from the center of the galaxy. (For comparison, the Sun is only about 26,100 light-years from the center of our galaxy.)

A big kick

How does such a massive object get ejected from its galaxy’s center? It takes a lot of energy: the equivalent of 100 million supernovas going off simultaneously. That exact scenario, of course, is not very likely — but such a blow could be delivered by the gravitational waves resulting from the collision of two large black holes. Gravitational waves, originally predicted by Albert Einstein and confirmed via the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory in 2016, are “ripples” in the fabric of space-time that occur when two massive objects, such as neutron stars or black holes, circle each other and merge.

3C 186’s host galaxy actually sports faint arcs of material, called tidal tails, that speak to the possibility of a past merger with another galaxy. And when galaxies merge, so too should their central supermassive black holes (see the 2011 discovery of two active supermassive black holes in Markarian 739 for a preview of such an event). But if the two supermassive black holes aren’t precisely matched in mass or rotation, the gravitational waves emitted as they swirl ever closer to each other will be unbalanced, stronger in one direction than any other. When the objects finally merge, the imbalance can give the resulting black hole a kick, sending it off in one particular direction.

“This asymmetry depends on properties such as the mass and the relative orientation of the back holes’ rotation axes before the merger,” explained team member Colin Norman of STScI and Johns Hopkins University. “That’s why these objects are so rare.”

If 3C 186 is truly what it appears, it would provide additional proof that such supermassive black hole mergers can occur.

There is a second possible explanation, though it’s less plausible in this scenario. Images taken with telescopes give no sense of depth — thus, the quasar could be associated with a foreground or background galaxy, and not the galaxy it appears to be escaping. If this were true, however, the team argues that the host galaxy of the quasar should be detected, and no such galaxy was seen.

The team hopes to make future observations of 3C 186 with HST and the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array, as well as other telescopes capable of providing a closer, more detailed look at the story behind this runaway black hole