This article originally appeared in our April 2015 issue.

The calendar says a quarter-century has passed since the space shuttle Discovery lifted its cargo of dreams into low Earth orbit. Elevated above the distorting effects of our planet’s turbulent atmosphere, the school-bus-sized Hubble Space Telescope promised clearer views of the night sky than humans had ever witnessed.

Sure there were glitches, most notably a primary mirror ground to the wrong shape and equipment that inevitably wore down under the harsh conditions of space, but NASA anticipated problems. A series of five servicing missions not only restored Hubble to its original specifications but also rebuilt the observatory into a 21st-century science machine. With new cameras and spectrographs operating nearly 24/7, much of what Hubble does today could hardly be dreamed of in 1990.

Just how much has Hubble accomplished during its 3-billion-mile (5 billion kilometers) journey around Earth? Scientists have published more than 12,000 papers in peer-reviewed journals using Hubble data. And not all of that science has come from new observations — researchers routinely plumb the Hubble archives, which currently hold more than 100 terabytes of data.

But to most of us, Hubble’s greatest contribution has been its images, which span the cosmos from next door (the Moon) to the universe’s earliest galaxies. In its 25 years, Hubble has snapped more than 1 million images of nearly 40,000 objects. The 28 we show here are the cream of the crop, though, truth be told, it would be easy to pick an entirely different set and say the same thing.

1. The Pillars of Creation

This may be one of the most recognized Hubble images. It captured the multi-colored glow of the gas clouds, the tendrils of dark cosmic dust, and the famous rust-colored pillars as seen in visible light.

Scientists recently targeted one of Hubble’s iconic subjects — the Eagle Nebula’s (M16) “Pillars of Creation” — with the space telescope’s Wide Field Camera 3 (WFC3). Inset: In the near-infrared, WFC3 shows the pillars silhouetted against background stars.

Scientists estimate that Abell 1689 contains thousands of galaxies and holds up to 500 trillion times the Sun’s mass. All that matter warps surrounding space, distorting and magnifying light from more distant galaxies.

Massive stars off the top of this image emit ultraviolet radiation that erodes the edges of the Cone Nebula (NGC 2264). This process liberates gas, and the ultraviolet light then excites this hydrogen-rich material, causing it to glow with a characteristic red color.

In visible light, this cloud of cold gas and dust appears dark against bright emission. But at the near-infrared wavelengths captured here, the nebula glows as its gas reradiates energy it absorbs from embedded young stars.

In January 2002, the star seen at center flared to become one of our galaxy’s most luminous. This view from two years later captures surrounding dust shells lit up by the eruption.

The Milky Way’s largest globular star cluster, Omega Centauri (NGC 5139), holds 10 million stars in a sphere some 150 light-years across.

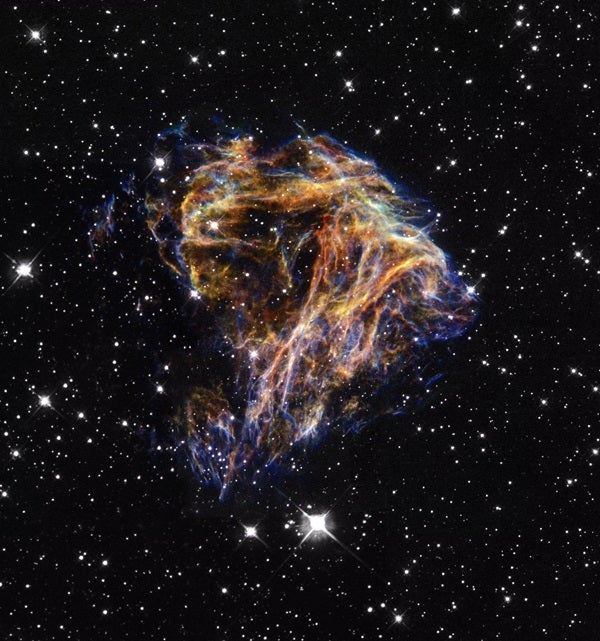

Hubble lets astronomers probe objects in nearby galaxies with a clarity previously impossible. Case in point: these splintered remains of a massive star that exploded 160,000 light-years from Earth in the Large Magellanic Cloud.

One of the Milky Way’s premier star factories is the Carina Nebula (NGC 3372), which came to life about 3 million years ago when stars first ignited in a cloud of molecular hydrogen. Ultraviolet radiation and stellar winds from these stars carved out an expanding bubble of hot gas. Now, as this gas plows into surrounding walls of cold hydrogen, it is triggering a second wave of star birth.

Fiery plumes of glowing hydrogen erupt from the central regions of this starburst galaxy, also known as M82. Colliding gas clouds there give birth to stars, many of which reside in giant clusters, at a rate 10 times higher than in the entire Milky Way.

When spiral galaxies interact, tidal forces warp their normal stately shapes. In this pair, the spiral arms of the top galaxy have been stretched and distorted. The bright blue star clusters at top reflect a firestorm of star formation initiated by the encounter.

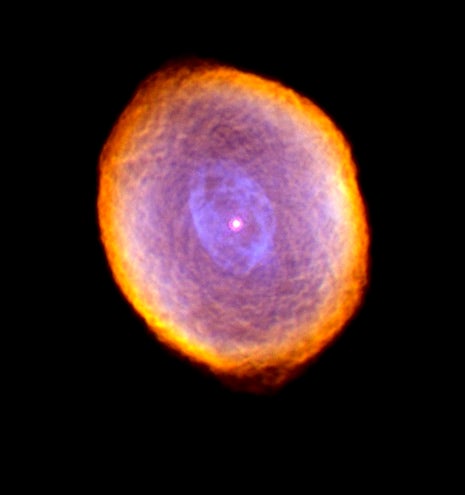

The intricate shapes of planetary nebulae, like the Helix Nebula (NGC 7293) and the others on this spread, make them among Hubble’s most dramatic subjects. These objects are the death throes of Sun-like stars, which puff off their outer layers — often several times — when they exhaust their nuclear fuel.

The progenitor star of the Spirograph Nebula (IC 418) cast off its outer layers multiple times, filling the planetary’s interior with lots of gas. A white dwarf stands out at the heart of the nebula; such stars energize the nebula’s gas and cause it to glow.

Astronomers nicknamed this planetary the Eskimo Nebula (NGC 2392) because it looks like a human face surrounded by a parka hood through earthbound telescopes. Hubble resolves the parka’s “fur” into myriad streamers of gas that resemble giant comets pointing toward the nebula’s center.

An irregular web of dark dust lanes crisscrosses the central regions of the Retina Nebula (IC 4406). Each of the lanes is roughly twice the size of Pluto’s orbit around the Sun. This image has been color-coded so hydrogen appears green, oxygen blue, and nitrogen red.

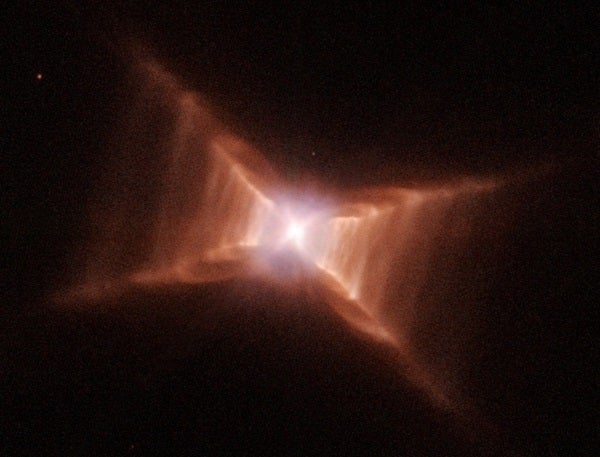

This object hasn’t quite reached the planetary nebula stage. Although the dying star at center has ejected much of its outer atmosphere, it has not yet evolved into a white dwarf. Cool dust, which forms the unique features that look like the rungs on a ladder, reflects starlight.

Through amateur telescopes, the Blinking Planetary’s (NGC 6826) central white dwarf is so bright that it overwhelms the nebula when viewed directly; the nebula “blinks on” when looking to the side. Hubble shows both clearly, along with two red patches near the nebula’s edge.

Mass loss in aging stars doesn’t always follow one pattern. The Cat’s Eye Nebula (NGC 6543) shows at least 11 concentric shells surrounding its central white dwarf, each one ejected at 1,500-year intervals. But about 1,000 years ago, the process changed and forged the bright irregular shells on the inside.

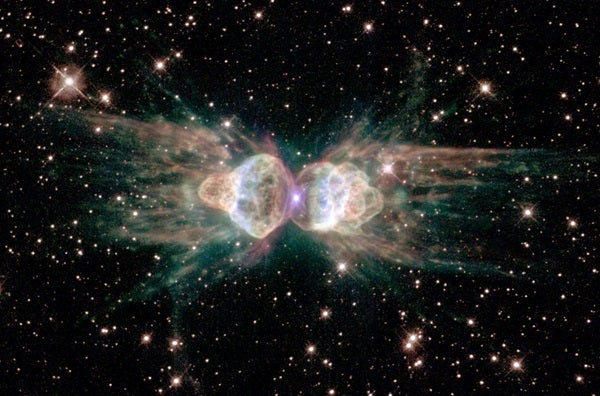

Astronomers aren’t sure what causes the narrow “waist” that lies between the two glowing lobes of the Ant Nebula, so called for its resemblance to the common insect. Some suspect an unseen companion sweeps material out of this region, while others think magnetic fields do the job.

The hot young stars in NGC 602 have carved out a cavity in a surrounding cloud of gas and dust located on the outskirts of the Milky Way’s satellite galaxy, the Small Magellanic Cloud. This image combines Hubble observations (shown as red, green, and blue) with X-ray (purple) and infrared (red) data.

Some 5,000 to 10,000 years ago, our ancestors likely saw a massive star explode in the constellation Cygnus. The star’s tattered remains now span 3°, or roughly 75 light-years. This close-up Hubble image shows a tiny part of it, barely 1-light-year across, at the Veil Nebula’s northwestern edge.

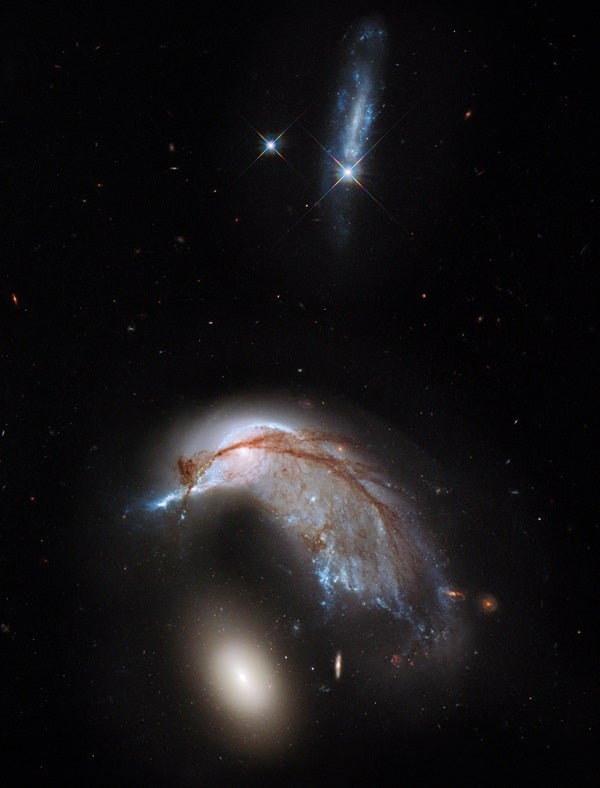

Tidal forces unleashed by the gravity of elliptical galaxy NGC 2937 (bottom) distort the previously normal spiral NGC 2936 just above it. The spiral’s arms and dark dust lanes now splay haphazardly across that galaxy’s disturbed disk, while blue knots trace the sites of ongoing star formation.

This giant spiral galaxy lies about 35 million light-years from Earth on the edge of the Virgo Cluster of galaxies. The Sombrero (M104) looks like a traditional Mexican hat because we view its dusty disk from just 6° north of the galaxy’s equator.

This hourglass-shaped stellar nursery spans 2 light-years and lies less than 1° from the Milky Way’s plane in the constellation Cygnus. The young star just below center (where the bluish lobes come together) sculpts the surrounding nebula’s intricate shape.

Galaxies NGC 4038 and NGC 4039 are merging. This cosmic collision is giving birth to billions of new stars, most of which belong to bright blue star clusters. The large yellowish globes at upper right and lower left are the cores of the original galaxies.

Hubble gives astronomers ringside seats to watch stars come to life in the Orion Nebula (M42). This dense cloud of gas, dust, and young stars lies just 1,500 light-years from Earth. The hottest, most massive stars already have emerged from their natal cocoons.