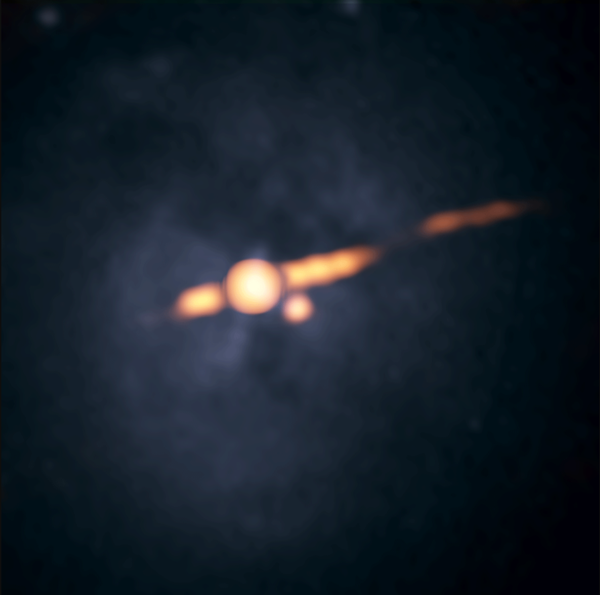

Cygnus A is an elliptical galaxy nearly 800 million light-years from Earth. In its center is a supermassive black hole at least a billion times the mass of our Sun, which appears to have recently gained a companion. New observations of this galaxy with the National Science Foundation’s Very Large Array (VLA) have unveiled a second bright object located near its central supermassive black hole — an object that radio astronomers think is a second supermassive black hole, destined to merge with the first.

Based on radio observations taken with the VLA in 2015 and 2016, astronomers have spotted a new object within 1,500 light-years of the galaxy’s supermassive black hole. This object was not visible in previous radio images of the galaxy, the most recent of which prior to the discovery were taken in 1996. It wasn’t until recent upgrades were made to the VLA in 2012 that observers considered a return to this famous galaxy, which was discovered by radio astronomer Grote Reber in 1939.

“To our surprise, we found a prominent new feature near the galaxy’s nucleus that did not appear in any previous published images. This new feature is bright enough that we definitely would have seen it in the earlier images if nothing had changed,” said Rick Perley of the National Radio Astronomy Observatory (NRAO) in a press release announcing the discovery. “That means it must have turned on sometime between 1996 and now.”

The new radio observations were made by a group of astronomers that included Perley and his son, Daniel Perley of the Astrophysics Research Institute of Liverpool John Moores University in the U.K., as well as NRAO researchers Vivek Dhawan and Chris Carilli. The results will be published in the Astrophysical Journal.

Following their 2015-2016 observations, the team used the Very Long Baseline Array in late 2016 to more clearly separate the new object from the galaxy’s previously known supermassive black hole. The new object also shows up in infrared images taken with the Hubble Space Telescope and at the Keck Observatory between 1994 and 2002, when it was originally thought to represent a dense group of stars. But the fact that the object has grown brighter in radio wavelengths since then has prompted new consideration.

Now, there are two possibilities based on the data: The new object is either a supernova explosion or a supermassive black hole. Supernovae are massive stellar explosions that are easily seen in distant galaxies. However, “Because of this extraordinary brightness, we consider the supernova explanation unlikely,” Dhawan said. The object is both too bright and has remained visible for too long to fit any current known supernova type.

Thus, said, Carilli, “We think we’ve found a second supermassive black hole in this galaxy, indicating that it has merged with another galaxy in the astronomically recent past. These two would be one of the closest pairs of supermassive black holes ever discovered, likely themselves to merge in the future.”

What does that kind of merger look like? At least two possibilities have recently come to light: the recoiling black holes CXO J101527.2+625911 and 3C 186.

So if this object is a billion-solar-mass black hole, why wasn’t it obvious before now? It may not have been as active, and only recently come into contact with new material, such as stars or dust, to accrete, causing it to “turn on” and give off observable radiation. “Further observations will help us resolve some of these questions. In addition, if this is a secondary black hole, we may be able to find others in similar galaxies,” said Daniel Perley.

Rick Perley was among the astronomers responsible for the very first observations of Cygnus A when the VLA first came online in the early 1980s. These observations provided the detail necessary for astronomers to begin understanding how supermassive back holes produce jets of materials that can span regions of space larger than their host galaxies. At the time, Daniel was only two years old.

“The VLA images of Cygnus A from the 1980s marked the state of the observational capability at that time,” said Rick Perley. “Because of that, we didn’t look at Cygnus A again until 1996, when new VLA electronics had provided a new range of radio frequencies for our observations.”

But now that these newest observations have revealed a surprise, Daniel Perley said, “This new object may have much to tell us about the history of this galaxy.”